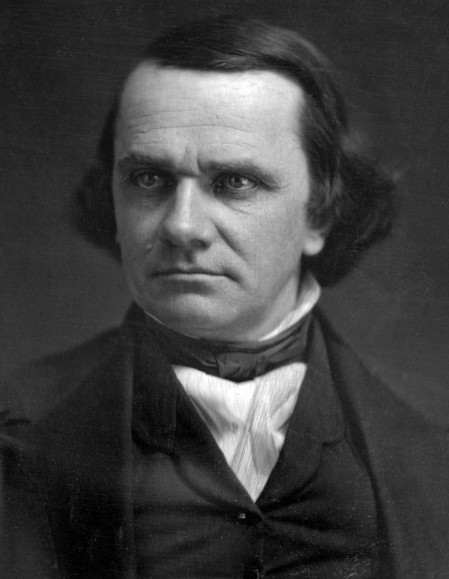

Stephen Douglas, the politician who was too smart for his own good

With the administration of George W. Bush still fresh in our collective memories, it’s easy to think that the problem with our system is the way it periodically throws stupid people into positions of power. And if that’s your diagnosis, the solution seems simple: just put smart people into those positions instead, and all will be well.

With the administration of George W. Bush still fresh in our collective memories, it’s easy to think that the problem with our system is the way it periodically throws stupid people into positions of power. And if that’s your diagnosis, the solution seems simple: just put smart people into those positions instead, and all will be well.

The problem, though, is that intelligence, in and of itself, is no guarantee of wisdom. Smart people tend to fall into different types of snares than stupid people; but fall into snares they do, and with distressing frequency. Self-destruction is not the exclusive province of the dumb.

History offers many examples of smart leaders who proved a bit too smart for their own good, but for my money the most impressive one is that of one of the great statesmen of 19th century America: Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, whose attempts to head off the looming sectional crisis over slavery ended up instead driving it into full-scale civil war.

We today remember Douglas primarily as an antagonist for Abraham Lincoln — a sort of designated foil, whose role in our memory is to erect obstacles that Lincoln has to overcome to realize his destiny as America’s greatest leader. But contemporaries of Lincoln and Douglas in the years leading up to the Civil War would have scoffed at such a characterization. To them, it was Lincoln who was the footnote to Douglas’ career, rather than the other way around.

Both men entered national politics in the 1840s, but the trajectory of their careers could not have been more different. Before his fantastically unlikely capture of the Republican presidential nomination at that party’s 1860 convention, Lincoln was generally considered a political B-lister, a small-town lawyer whose lackluster public career had been marked only by a single term in the House of Representatives and an unsuccessful bid for a U.S. Senate seat. Douglas, on the other hand, was a titan, one of the best-known politicians in America and the undisputed master of the complicated politics of the U.S. Senate. Elected to his first national office in 1842, by 1846 he had reached the Senate and throughout the 1850s he was one of the national leaders of the Democratic Party and a leading candidate for that party’s Presidential nomination.

While Lincoln’s stalled career gave him few opportunities to affect the crisis that was slowly building in American life, Douglas’ meteoric rise put him right at the center of events. And he tried, several times, to use that position — and the considerable rhetorical and organizational talents that had gotten him there — to defuse that crisis. Each time, Douglas devised a plan of action that was striking in its cleverness. And each time, that very cleverness proved to be the plan’s undoing, planting a bomb that would end up causing the nation more damage than it prevented.

Washington, 1854

The first of Douglas’ great miscalculations was the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

The great question of American political life in the first half of the nineteenth century was how to keep the nation’s division between slave states and free states from tearing it apart as the nation expanded. The stability of the early Republic rested upon a delicate balance of power; as the nation grew, and new states began to be carved out of newly won territories, Congress was forced repeatedly to act to establish some kind of equilibrium. The first crisis came after the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France; the mechanism established to address that crisis, the Missouri Compromise, established the principle that each slave state admitted to the Union should have a corresponding free state admitted with it to preserve the balance. This ensured that both sides had the same number of votes in the Senate, where each state was allocated two Senators; and since failure to pass the Senate would stop any bill from becoming a law, legislation that overtly favored one section of the country could be put down there by the other. Neither section, therefore, had reason to fear that the other could interfere with its internal institutions unilaterally.

To make it clear where each should come from, the Missouri Compromise established a boundary line (36°30′ north) across the middle of the nation, north of which could only be created free states and south of which could only be created slave states. This tenuous agreement held when further territory was wrested from Mexico in the 1840s in the Mexican-American War; the disposition of that territory was settled by another compromise, the Compromise of 1850, which upheld the principle of balancing free and slave states.

The matter came to a head again in 1854, however, when two new states, Kansas and Nebraska, petitioned for statehood. Both were north of the Missouri Compromise line, meaning that by the terms of that agreement they would have to be admitted as free states. At the same time, Congress was debating the notion of how best to build a transcontinental railroad, and various cities were put forward as the eastern terminus of such a railroad’s route.

Senator Douglas, being from Illinois and an ardent supporter of railroad expansion, wanted to establish the railroad’s start at Chicago, since doing so would make Illinois the gateway to the West and bring a huge volume of business through that city. Southern leaders, however, had the same dreams for their own cities, such as New Orleans. Douglas, seeking to kill two birds with one stone, devised a new compromise: the South would accept the Chicago route for the railroad, and in return, the old Missouri Compromise line would be repealed. The question of whether to admit Kansas and Nebraska (and, indeed, all other future territories) as free or slave states, no longer a simple question of geography, would be left instead to the voters of each territory to settle in a vote — a solution that became known as “popular sovereignty.”

(Douglas’ initial proposal, notably, had included popular sovereignty but had not explicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise line. Southerners, however, feeling that a free territory would inevitably vote to become a free state, pushed him for full repeal. The arguments of one of them, Senator Archibald Dixon of Kentucky, eventually swayed Douglas to support full repeal, either from the strength of his logic or the looming threat that without it the South would not back his compromise. “By God, sir,” he told Dixon, “you are right. I will incorporate it into my bill, though I know it will raise a hell of a storm.”)

This compromise, while winning Douglas the support he wanted for his Illinois railroad plan, proceeded to backfire on the nation in spectacular fashion. Since the question of whether a territory would be slave or free now hinged on the number of voters within it who supported each, pro- and anti-slavery activists (including one anti-slavery fanatic who would pop up again later on: John Brown) rushed into Kansas and Nebraska, hoping by their presence to establish a majority for their side. Within a year open violence had broken out between the two factions, earning Kansas the sobriquet “Bleeding Kansas.” Rather than settling the question of whether Kansas should be free or slave, the legislation and the violence it created ended up leaving it wide open, as neither side would accept a vote that went the other way as legitimate.

Beyond the two territories that had prompted the debate, the effects were dramatic as well. Northerners, who had assumed that territories north of the old compromise line were safe from the expansion of slavery, suddenly found themselves confronted with a new reality in which any territory (or established state!) could switch from free to slave with a single vote. Many of those Northerners had previously been content to accept slavery in the South, so long as it never touched them directly; now they began to worry that someday they would have to confront the issue in their own communities. This caused the first major push that drove many of these previously apathetic citizens into supporting abolition. Anger at Douglas flared up across the North; as he himself put it, “I could travel from Boston to Chicago by the light of my own effigy.”

Freeport, 1858

One of these newly radicalized Northerners was an Illinois lawyer and minor-league politician named Abraham Lincoln. Disappointed by his meager success in his single term in Congress, he had put himself in the early 1850s into a sort of voluntary political retirement. But the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act shocked him enough to compel him to re-enter public life.

On October 16, 1854, Douglas addressed an audience at Peoria, Illinois, promoting the concept of popular sovereignty. Lincoln was there, and spoke to the crowd in response:

The doctrine of self government is right—absolutely and eternally right—but it has no just application, as here attempted. Or perhaps I should rather say that whether it has such just application depends upon whether a negro is not or is a man. If he is not a man, why in that case, he who is a man may, as a matter of self-government, do just as he pleases with him. But if the negro is a man, is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself? When the white man governs himself that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism. If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that “all men are created equal;” and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another…

But you say this question should be left to the people of Nebraska, because they are more particularly interested. If this be the rule, you must leave it to each individual to say for himself whether he will have slaves. What better moral right have thirty-one citizens of Nebraska to say, that the thirty-second shall not hold slaves, than the people of the thirty-one States have to say that slavery shall not go into the thirty-second State at all? …

Whether slavery shall go into Nebraska, or other new territories, is not a matter of exclusive concern to the people who may go there. The whole nation is interested that the best use shall be made of these territories. We want them for the homes of free white people. This they cannot be, to any considerable extent, if slavery shall be planted within them. Slave States are places for poor white people to remove FROM; not to remove TO. New free States are the places for poor people to go to and better their condition. For this use, the nation needs these territories…

Little by little, but steadily as man’s march to the grave, we have been giving up the OLD for the NEW faith. Near eighty years ago we began by declaring that all men are created equal; but now from that beginning we have run down to the other declaration, that for SOME men to enslave OTHERS is a “sacred right of self-government.” These principles can not stand together. They are as opposite as God and mammon; and whoever holds to the one, must despise the other.

As you can see from the third paragraph quoted above, Lincoln’s Peoria speech was not a full-throated call for an end to slavery and the integration of black and white. It marks the beginning of his journey towards emancipation, not the end. But it marked him out for the first time as having definitively come down on the anti-slavery side of the question — and as an eloquent home-state opponent for Douglas.

The two men would meet again in 1858. Lincoln, propelled into the limelight by the increasing urgency of the slavery question, had been put forward by the newly formed Republican Party as Douglas’ opponent for re-election to his Senate seat. The two candidates clashed in a series of debates across Illinois, debates that would become known to history as the Lincoln-Douglas debates. And in these debates, slavery and Kansas-Nebraska — a bill with which Douglas’ name had become inextricably linked — were the primary subject.

Lincoln was, among other things, a canny politician; and as such, he recognized the unpopularity of Kansas-Nebraska in free Illinois, and sought some way to nail Douglas’ ambitions firmly to it. But he knew that Douglas was a canny politician too, and if left to his own devices would frame his support for the bill in some way which did not make him seem objectively pro-slavery. So Lincoln set out to build a trap for him — a rhetorical snare into which Douglas could be enticed to step without realizing until it was too late what he had done.

At the town of Freeport, Illinois, on August 27, 1858, Lincoln sprang his trap. It consisted of a simple question:

Can the people of a United States Territory, in any lawful way, against the wish of any citizen of the United States, exclude slavery from its limits prior to the formation of a State Constitution?

This question is not only simple; it is deceptively simple. For Lincoln designed it to throw Douglas upon the horns of a dilemma, thanks to a Supreme Court decision issued the previous year.

In the landmark case of Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Court had ruled that African-Americans had no right to be free anywhere in the United States — an expansion of the “right” to own slaves that went far beyond Douglas’ principle of popular sovereignty, since it implied that even if the people of a state wished to vote freedom for their black neighbors, they had no legal right to do so. Unsurprisingly, Dred Scott agitated the North even more than Kansas-Nebraska had. But Douglas, as a legislative leader and a man who had made his career working within the system, had refused to denounce the decision as illegitimate. The purpose of Lincoln’s question was to force Douglas to choose between supporting the legitimacy of the Court’s decision and supporting his own doctrine of popular sovereignty. Did he still believe that the people of a territory had the right to vote freedom for blacks? If he did, didn’t it logically follow that he should be fighting the Court’s decision, which explicitly removed that right? In this question, to support one was to oppose the other; there was no middle ground for the great compromiser to save himself by standing upon.

Or so Lincoln thought. Douglas, thinking fast, took Lincoln’s choices and carved out a third path which allowed him to escape the carefully laid trap:

It matters not what way the Supreme Court may hereafter decide as to the abstract question whether slavery may or may not go into a Territory under the Constitution, the people have the lawful means to introduce it or exclude it as they please, for the reason that slavery cannot exist a day or an hour anywhere, unless it is supported by local police regulations. Those police regulations can only be established by the local legislature; and if the people are opposed to slavery, they will elect representatives to that body who will by unfriendly legislation effectually prevent the introduction of it into their midst. If, on the contrary, they are for it, their legislation will favor its extension. Hence, no matter what the decision of the Supreme Court may be on that abstract question, still the right of the people to make a Slave Territory or a Free Territory is perfect and complete under the Nebraska bill.

Dred Scott, in other words, was completely compatible with the principles of Kansas-Nebraska. The Court had said that territories could not prevent slave owners from bringing in their slaves by referendum; but, practically speaking, slavery could not exist in a territory if it were not propped up by a web of local laws and regulations, so a state could still make itself “free” by simply refusing to establish those laws and regulations. Slave owners could still bring their slaves in, but who would want to bring slaves into a place where no laws existed to help you recover them if they ran away, or to allow you to punish them if they refused to work? Nobody.

It was an ingenious argument, and it won Douglas victory over Lincoln in that year’s election. But as with Kansas-Nebraska, while it solved an immediate problem for Douglas, it did so in a way that planted the seeds of future trouble for him as well. Douglas’ third way became known as the “Freeport Doctrine,” and while it palliated Illinois, it infuriated the South. Here, Southern leaders thought, was a glimpse into the real way Douglas’ mind worked, setting up formal approval of slavery while at the same time winking to anyone who opposed it that nobody would stop them if they used local law to harry slave owners out of their territory. It made Douglas appear Janus-faced, with one message for the South and a completely different one for the North. And as Douglas rose to become the leader of the national Democratic party, this gave southern Democrats cause to wonder: if our leader is willing to sell us out, will our party do so as well?

Charleston, 1860

This uneasiness with Douglas as a leader boiled over two years later, when the Democrats met in Charleston, South Carolina to nominate a candidate for the 1860 Presidential election.

Douglas, as the only national Democratic leader with a foot in both the Northern and Southern wings of his party, was the front-runner for that position. But it quickly became clear when the convention opened on April 23 that the depth of the South’s anger at the Freeport Doctrine threatened to make it impossible for him to win nomination. Southern “fire-eaters” felt that Douglas’ creation of that doctrine made him an unacceptable candidate, and began to agitate for more openly pro-slavery leaders, such as Robert M.T. Hunter of Virginia and James Guthrie of Kentucky.

Convention rules required a candidate to win two-thirds of the delegates in order to secure the nomination, and as the ballots were cast, it became clear that despite the support of most Northern delegates Southern dissatisfaction with Douglas was great enough to prevent him from reaching that level of support.

The fire-eaters, believing they had Douglas cornered by his own ambition, presented him with a way to break the impasse. He could win their support, they said, by presenting them with a demonstration of his loyalty to the Southern cause — a push to include a call for a Federal slave code in the party platform. The establishment of a national set of laws governing how slaves were to be treated would render the Freeport Doctrine moot (since there would no longer be a need for previously-free states to establish local laws to allow slavery to operate) and put Douglas firmly in the pro-slavery camp. And with the Southern delegates in his pocket, Douglas would have more than enough to win the nomination.

The Southerners didn’t only approach Douglas with this carrot, though. They brandished a stick as well. If Douglas refused to support adding the call for a national slave code to the platform, they threatened, they might be forced to conclude that there was no candidate at the convention they could support — and if that happened, they might simply walk out. Such a walkout would mean doom for the party’s chances in the general election; much of the Democratic Party’s strength in 1860 was in the South, so if Southern Democrats refused to support the party ticket there was no way it could overcome the Republican opposition, whose base was a unified North.

Considering this offer, Douglas knew that it was not as simple as the fire-eaters made it sound. Abandoning the Freeport Doctrine and supporting a national slave code might win him Southern delegates, but it would at the same time alienate Northern ones — the very people he had devised the Freeport Doctrine to appease. But he definitely could not win the nomination with just the Northern delegates alone. Just as he had been in Washington and Freeport, he was trapped — unless he could devise a new way out.

And, great compromiser that he was, he managed to find one. He would not, he told the Southern delegates, support adding a call for a national slave code to the party platform. What he would do, however, was support adding a call for questions of slave owners’ property rights to be decided by the Supreme Court, rather than by local courts and laws.

As with his other compromises, this represented a brilliant threading of the needle. It allowed him to avoid jumping firmly into the pro-slavery side of the debate, since his plan would not definitively establish any laws favoring slave owners. And at the same time, he thought, it should be enough to appease Southerners, since the Supreme Court had demonstrated itself in Dred Scott to be a strongly pro-slavery institution. The pitch to the fire-eaters was simple: this will effectively get you what you want. To avoid inflaming Northern opinion, it won’t do it overtly and explicitly; but in practice, it will still be done. Shouldn’t that be enough?

It was not.

Douglas put forward his compromise, and it garnered enough support to be included in the party platform:

Inasmuch as difference of opinion exists in the Democratic party as to the nature and extent of the powers of a Territorial Legislature, and as to the powers and duties of Congress, under the Constitution of the United States, over the institution of slavery within the Territories,

Resolved, That the Democratic party will abide by the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States upon these questions of Constitutional Law.

There were some Southern Democrats who could swallow this evasion. But the hardest of the hard-core — the fire-eaters — could not. In the first act of what would become a long list of secessions, fifty of them walked out of the convention on April 30, throwing the Democrats into chaos and forcing the convention to close and reconvene later.

“Later” came in June, when the Democrats attempted to reconvene in Baltimore. What began as one convention quickly split into two: one for delegates who had not walked out in Charleston, and another for those who had. With his most vociferous opponents having left for the splinter convention, Douglas had little difficulty winning nomination from those who stayed; but the nomination he finally won was damaged goods, since it was only for the leadership of one part of a fatally split party. The fire-eaters nominated their own candidate, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, putting Douglas in the awkward position of having to run a national campaign for President against two candidates (Breckinridge and the Republican candidate, Lincoln) whose support was explicitly sectional.

It was hopeless, but Douglas tried it anyway. Fearing that the split in the Democratic Party presaged a split in the nation itself, he broke one of the great unwritten rules of the presidency: that it was beneath the dignity of Presidential candidates to campaign in person. He launched an energetic campaign that took him across the country, personally addressing crowds wherever he went. But he was a compromiser in a moment when compromise was disdained as appeasement, and had to struggle everywhere against suspicions that no matter what he told one crowd he really believed something different. He had never supported secession, and in his campaign swings through the South he bravely tried to convince Southern audiences that they should not either — even calling for a tight noose for the necks of traitors:

We do not stop to inquire whether you here in Raleigh [, North Carolina] or the Abolitionists in Maine like every provision of that Constitution or not. It is enough for me that our fathers made it. Every man that holds office under the Constitution is sworn to protect it. Our children are brought up and educated under it, and they are early impressed by the injunction that they shall at all times yield a ready obedience to it. I am in favor of executing in good faith every clause and provision of the Constitution, and of protecting every right under it, and then hanging every man who takes up arms against it. Yes, my friends, I would hang every man higher than Haman who would attempt by force to resist the execution of any provision of the Constitution which our fathers made and bequeathed to us.

To the end, to Election Day, he fought ferociously for his dream of a Union preserved through compromise. But he was simply the last to realize that this dream, which had held the nation together for decades, was now well and truly dead. He ended up coming in second in the popular vote, behind Lincoln, but he carried only one state (Missouri) and his support was otherwise scattered across so many places that out of 303 total electoral votes, he won only twelve. (Breckinridge, the fire-eaters’ candidate, only got half as many total votes as Douglas, but since those votes were concentrated in the South they earned him 72 electoral votes.) His fear of a national schism had been well-grounded; despite all his efforts, within six months the fire-eaters would take their states out of the Union, and Southern shells would be bursting over Fort Sumter. The conflict he had spent his life trying to prevent had finally come — brought on, in no small part, by his efforts to prevent it.

He would live to see the failure of his efforts, but only just. The strain of his 1860 campaign wore upon him, and by early 1861, as the nation began to fall apart, his health collapsed as well. He shared the platform with Abraham Lincoln one last time, at Lincoln’s inauguration on March 4; in a gracious gesture, he held the hat of the man whom history had propelled onto the trajectory he had dreamed of for himself. On June 3, 1861, just days before the armies of North and South met for the first time at the First Battle of Bull Run, he died in Chicago.

Our nation has occasionally elevated fools to high office, and suffered for it. But Stephen A. Douglas was no fool. If anything, he was the opposite — a man intelligent enough to consistently find ways to square impossible circles. But his life instructs us that intelligence, alone, is not enough to a leader make. It needs to be leavened with wisdom, and wit, and humility — none of which were Douglas’ strong suits. Thrust into an age of crisis, he fought throughout his career to erect castles of the mind strong enough for a nation to take shelter in, only to discover that to build a castle of the mind is not enough. You need to know how to convince the nation to shelter with you within it, as well. And it was this failure — his failure to understand that politics is not so much about demonstrating intellect or scoring debating points as it is about being a good shepherd — that doomed him to become a footnote to the tale of his times.

Comments

Iona

March 6, 2013

4:37 pm

Your style is unique in comparison to other people I’ve read stuff from. I appreciate you for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I will just book mark this site.

Mark Curran

May 24, 2015

1:26 am

In all honesty, our article seems rather juvenile, taken it seems directly from standard books, and not from original documents.

No mention of Douglas relationship with David Rice Atchison? Are you kidding, or just unaware? Atchison got Douglas to push for opening up Kansas for slavery. Contrary you shallow and rather stupid meme, Douglas WAS NOT for popular sovereignty, despite the public insistence that he was. To think Douglas was for actual popular sovereignty you have to dismiss as wrong, or just not know, what the LIncoln Douglas debates were about.

Lincoln specifically went after Douglas for the ruse of pretending to be for popular sovereignty, while actually inserting language into the Kansas Act, that prevented it, as events would show.

Do you now know about this — at all? Or you just think Lincoln and others were wrong about Douglas?

Actually, Lincoln and others were quite right, as Atchison’s actions in Kansas proved. Atchison and Douglas both both got KS act passed, after which Atchison personally went to Kansas and started his bullying, then terrorizing, then killing, to spread slavery.

You really should learn about David Rice Atchison, who his superior were (Douglas was, as Chairman of House and Senate committee on Kansas) and Jeff Davis was, as Sect of War.

In fact, you also have to be unaware of Charles Sumners famous speech about Atchison, the speech he was nearly killed for. Sumner exposed -in great detail — what Atchison was up to, and had been up to, since he and Douglas got Kansas Act passed.

You also have to be unaware of the hundreds of newspaper articles at the time, about Douglas’s duplicity. Folks who knew Douglas, said right away, when his first proposed KS Act, that this was a ruse and was actually to PREVENT, not allow, Kansas citizens to reject slavery.

Indeed, the language Douglas inserted in KS act,and refused to get rid of, was the exact language later used by pro slavery folks in KS, to justify their killing sprees, and their violence against citizens of Kansas, in their efforts not only to vote against slavery, but to even speak against slavery.

True, this level of understand of Douglas is often missed, by stupid people who, like you, just repeat the BS.

But when you understand Lincoln and the debates, this is central — Douglas, as Lincoln pointed out, was actually preventing folks from voting against slavery.

Try again. This time, learn what Lincoln was talking about in Lincoln Douglas debate, about popular sovereignty.

Also, learn how Douglas repeatedly and loudly accused Lincoln of being a “Nigger lover” and “obsessed with equality for the Nigger”. Douglas told crowds repeatedly, and with great emphasis, that Lincoln wanted their daughters to sleep with and marry “Niggers”.

Furthermore, Douglas insisted that blacks were, by authority of the SCOTUS, not people, not humans at all, but property. Lincoln, by his “obsession” with equality for the “NIGGER” was “preaching revolution? Blacks are not equal, and to say they were, was “contrary to the Supreme Court of the United States?

Douglas was very specific, the founding fathers were wrong and in error, when they said all men are created equal. The Taney court said as much — and they did!

Douglas again, and again, betrayed whoever he was aligned with. He double crossed those who passed the MO compromise, calling it “a sacred covenant” that “no fool would dare to ever repeal” or words to that effect.

But not three years later, Douglas and Atchison came up with “the first machinery” as LIncoln called it, to force slavery into Kansas. The machinery was the Kansas Act, and LIncoln got back into politics, because of it.

By the way, the silly comments you describe as Douglas, was bullshit made up later. Atchison boasted he had written the Kansas Act, though oddly Douglas would claim in great detail he came up with the language himself.

The particular wording in the Kansas Act made it an Orwellian bit of double speak, claiming people in KS were “perfectly free” to decide slavery issues themsleves, but the details were such that was not the case at all. Plus, Atchison, the cosponsor of the legislation, as indicated, personally went to Kansas after the Act passed, and made physically sure — by hiring hundreds of men — that Kansas citizens would pay a dear price if they even spoke against slavery, much less tried to vote against it.

Remember, Atchison and DOuglas were partners. Douglas stood behind Atchison, for years, claiming Atchison was the most gentle and non-violent man, and mos true patriot, he ever met. When Atchison became a political liability, however, Douglas claimed there were only traitors and patriots, and those who were against Union, were traitors. But that was just before his death, when the South had gotten what they wanted from him — to open up Kansas for slavery.

Douglas, in a late life discussion with John Palmer, oddly told Palmer that the Republicans “had me all wrong” regarding Kansas. Almost hilariously, Douglas told Palmer he was just trying to set up Davis, in Kansas, so Davis would “over play his hand” and be defeated easily earlier.

One of the strangest things I ever heard. His actions regarding Atchison were in order to set up Davis? Holy cow, was that guy eager to sell out anyone, and justify anything.

http://trashinglincoln.blogspot.com/