Creation is a beautiful torture

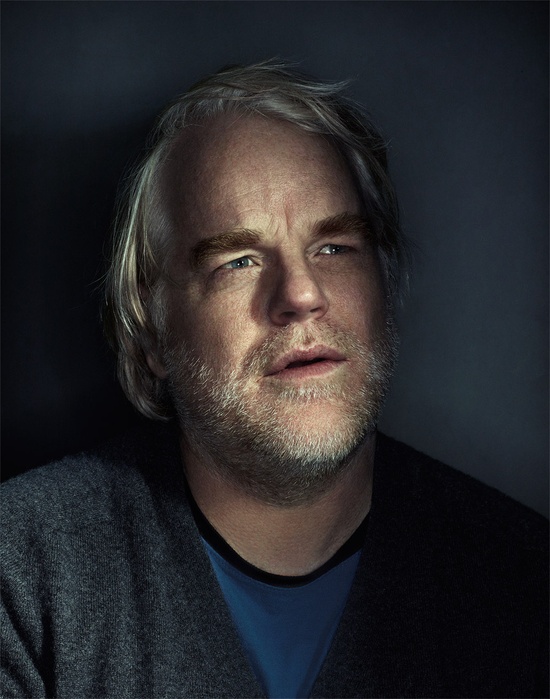

Philip Seymour Hoffman. Photograph by Miller Mobley.

As I imagine many of you were, I was taken aback to learn this morning of the death of actor Philip Seymour Hoffman, apparently from a heroin overdose, at the too-young age of 46. He was one of the great actors of his generation, so his loss will be keenly felt by all who love film and theatre.

I was surprised though, as I saw people I knew pay tribute to him on social media, to see how many of them expressed surprise at why someone like him would turn to drugs. He was successful, famous, widely renowned as one of the greatest in his profession, the argument went; what would someone with all those blessings need to run from?

I don’t claim to have any particular insight into Mr. Hoffman’s psyche, but a quote from a 2008 New York Times Magazine profile of him resonated with me as at least a partial explanation:

For me, acting is torturous, and it’s torturous because you know it’s a beautiful thing. I was young once, and I said, That’s beautiful and I want that. Wanting it is easy, but trying to be great — well, that’s absolutely torturous.

I think any creative person will understand what he was getting at. When you first start thinking about making something, doing something, the vision of it in your head is pure, perfect; you see not the thing itself, but the Platonic ideal of the thing, the thing as it should be. And then you spend some amount of time getting your hands grubby, rooting around in the mud and clay of everyday human experience, trying to bring that thing to life — only to discover, once you’ve finally finished, that the product of your labors is flawed. It’s not perfect. It’s not the vision that shimmered in your head, but an imperfect interpretation of it; a translation by someone who doesn’t really speak the language.

This is the inevitable end state of all creative endeavors. If you care about the work — really care about it — you quickly find that no matter how hard you work, how hard you try, inevitably the final result disappoints you. The only real questions are in what way and by how much.

I experience this all the time in my own work. I have high standards for what’s good and what isn’t, and even the projects that complete with happy clients and happy users usually leave me thinking of a couple of small things that I could have done better. This might sound like perfectionism, but I don’t think that’s it; it’s more just the frustration of having seen the perfect version of it in my head, and then not having the talent, the ability, to realize it. (And I’m just a schmuck who builds Web sites! Hoffman’s work was scrutinized to a degree mine will never be.)

The thing is, though, nobody has that talent. We’re all human beings, imperfect ourselves, and our imperfection inevitably seeps through into our works. Or as Kant put it, “out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.” The vision in your head is of the straight thing, but the only wood you have to build with is that crooked timber. The best you can do is never good enough. But understanding that intellectually is one thing, while understanding it in your heart and gut is something else entirely. So learning how to cope with that feeling and move past it without letting it erode your self-esteem becomes a valuable survival skill.

I have to think this struggle must be especially frustrating for actors who work in film. On the stage, you give a new performance each night, so if tonight’s performance doesn’t feel right, you can tell yourself that tomorrow’s will be better. But film is permanent, immutable; at some point the director says “print” and your performance gets frozen in amber. Which means that you, the actor, lose something most other creative people have: the thought (even if it’s usually just an illusion) that someday you can go back and fix it. Authors can issue revised editions of their books; musicians can publish remixes of their songs; but for the film actor, once the performance is done, it’s done.

(Which isn’t to say that the film itself will never be revisited; the director might come back and fiddle with the film someday, but even in that case all the power in the situation is hers, not yours. Nobody’s going to ask you to come out and shoot new scenes for that. And of course, time passes, so perhaps you you don’t look quite the same now as you did then — making it impossible to step back into the role even if you want to, unless you have access to a time machine.)

Hoffman was right; it’s torture. Or it can be torture, at least, if you don’t learn how to live with it. So for someone like him — someone who is universally spoken of as caring about his work even more than the average artist — I can totally see how that person might find himself reaching for anything that might promise relief, even if that relief is fleeting and ultimately self-destructive.

The main thing about torture, after all, is how much you want it to stop.

Comments

DaisyDee

February 3, 2014

12:01 am

He was a great actor and artist, for sure. The thing about great artists is that they also tend to be very self-centered. PSH left behind 3 children, and while I’ll never know the tumult within his psyche or the extent of his inner demons, I do feel his drug relapse was self-indulgent and irresponsible. As a result, his death leaves me feeling shock and then disappointment.