Braddock’s Dark and Bloody Road

Today, a history lesson.

Not far from my apartment in Alexandria, Virginia, a road begins. It looks like any other suburban road, except for a small marker capped with a bronze cannon.

This cannon marks the beginning of Braddock Road. Today, Braddock Road is a significant traffic artery in Northern Virginia; thousands of people pass over it every day without a second thought.

But today is the 250th anniversary of the christening of this road — and it got its name from one of the most violent convulsions of early American history, from which came the first glimmer of possible independence from Britain.

That convulsion began when an army set out along this very road that we drive upon today — and it set in motion a chain of events that would change the history of the world.

Empires Colliding: America in 1755

By 1755, colonization of North America had reached its (perhaps) inevitable conclusion: after brushing away all the minor colonizing powers, the two that remained, France and England, eyed each others’ holdings warily. Neither believed that the other would permit them to continue to colonize unmolested. Both were determined to hold on to their position in this rich new land.

Beyond that, however, any similarities in the two powers’ approaches to colonization ended. England’s colonies, clustered along the Atlantic coast and hemmed in to the west by the Appalachian Mountains, were teeming, populous centers of commerce. By contrast, the French colony of New France was only sparsely populated; the social pressures that led thousands of Englishmen to leave their home for the New World were simply not present in the more stable, aristocratic French society. New France was a land that a few hardy colonists and enterprising voyageurs called home, but England’s colonies were rapidly growing into a culture all their own.

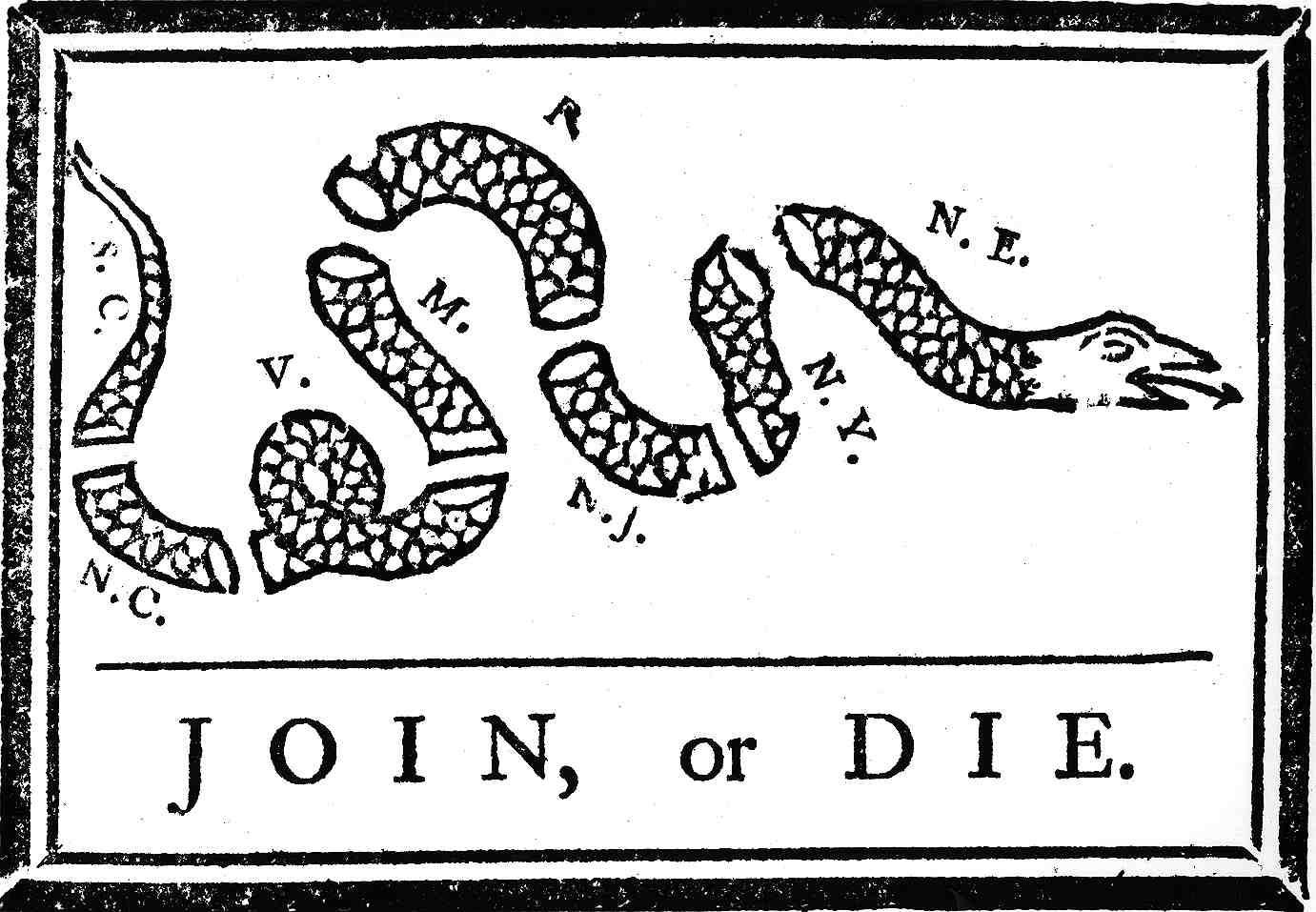

This is not to say that the English model of colonization was inherently superior to the French, however. While New France was small in population, it was all directed by the same authority: the royal court in Paris. England’s colonies, in contrast, each went their own way; their local governors, appointed by the King, had broad authority to act in his name however they saw fit. The result was that the English were (in)famous for squabbling amongst themselves, even in moments of grave danger. Benjamin Franklin protested this tendency with what has been called the first editorial cartoon ever printed:

This inability to unite would prove costly in the future.

Perched precariously between the two colonial powers were the nations of the Native Americans; and among these, the most strategically placed was the Iroquois Confederacy, a remarkable federation of tribes that had risen to power in upstate New York through political innovation and ruthless conquest. With the French pressing on their borders from the north and west and the English from the south and east, the Iroquois found themselves pushed to choose: would they ally with one colonial power, or try to stay neutral and steer a middle course?

Fort Necessity

As England’s colonies grew, and English colonists continued to stream to the New World, French policymakers began to fear that they would be crowded out of their own colony. Even with the formidable barrier of the Appalachians in the way, the English were already starting to expand westward; what would happen when the numbers spilling over the mountains grew large enough to displace the tiny population of New France altogether?

Their small population, and a lack of interest at court in Versailles, made a direct confrontation impossible. The French colonial authorities therefore undertook to try and dam the flood by establishing a series of forts at strategic locations in New France — forts that would make English expansion impossible by controlling traffic along the rivers, which (in an age when the fastest land transportation was by horse) were the arteries of commerce and communication.

Of all the river points to be secured, the most important was one where two smaller rivers — the Allegheny and Monongahela — joined to become a much larger river, the Ohio. Since their only access to the Ohio was via these rivers, a fort placed here could prevent the English from floating even a rowboat onto the broad highway of the Ohio. The French rapidly began construction of a fort at this critical point, and christened it Fort Duquesne.

Word of the construction of this fort quickly got back to the British, and they decided to respond — but, in true colonial fashion, they could not pull together a united effort. Instead, the governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, unilaterally sent a small force of militia towards Fort Duquesne to inform the French that, as far as he was concerned, that land belonged to Virginia. At the head of this force he placed a young militia officer from the state’s planter aristocracy with no prior military experience — a fellow named George Washington.

Washington’s expedition ended in disaster when he ambushed a French force and killed one of their officers. Realizing the French would strike back, he cobbled together a makeshift fort of his own near Fort Duquesne and christened it “Fort Necessity“.

Fort Necessity was to have only a brief life. Angry and out for revenge, the French soon descended upon it, and they far outnumbered Washington’s tiny force. After a day’s fighting, Washington surrendered — the only time in his career he would ever do so — and led his defeated force back to Virginia in shame.

News of the Virginians’ defeat shook the British colonies. Clearly the French meant business; and the fort they were building at the forks of the Ohio now loomed in the British imagination as a kind of colonial Death Star.

It was obviously time to call in the professionals.

Comments

TerryB

October 21, 2008

6:09 pm

You have an excellent sense of history and write it well. I enjoyed it.