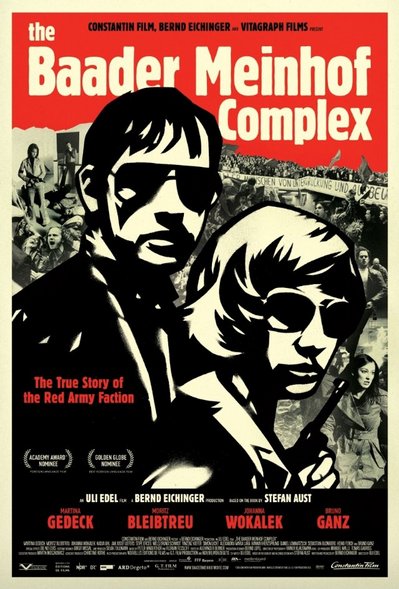

The Baader Meinhof Complex

With homegrown terrorism bubbling into the news in America again, now seemed like an opportune time to check out a movie I’d been hearing good buzz about since it hit the awards circuit last year.

The Baader Meinhof Complex (Der Baader Meinhof Komplex) tells the story of Germany’s most notorious domestic terrorist group, the Red Army Faction (abbreviated RAF) — a group of disaffected leftists who paralyzed German politics with violence for nearly the entire 1970s, known in popular jargon of the time as the “Baader-Meinhof gang” after two of its leaders, Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof.

For Americans unfamiliar with German history, it can be hard to understand the impact the RAF had. America had its own left-wing terror groups during that period, such as the Weather Underground, but in comparison they were amateurish affairs, fringe operations at best. The RAF, on the other hand, was brutally central. Bombing government offices, robbing banks, kidnapping and assassinating political figures they opposed — all in the name of a fiery leftist creed that poked uncomfortably at the guilt Germans still felt about succumbing to Nazism — they left an indelible impression on German politics of the era.

This is, as you might imagine, a touchy subject for a German film to address, even today. Not quite as touchy as 2004’s Downfall (Der Untergang), which touched on a wire even more live — the memory of Adolf Hitler himself — but touchy nonetheless. It was easy to imagine it going off the rails in two directions: either glossing over the real social issues that made many Germans of the time sympathetic to the RAF’s aims to paint them as nihilistic, one-dimensional villains, or going too far in the other direction and glamorizing them as misunderstood youth who weren’t terrorists so much as kids who accessorized their hip ’70s outfits with submachine guns and TNT.

I was encouraged, therefore, to hear that the film was written and produced by Bernd Eichinger, who had also written and produced Downfall; his success at making Hitler a complex, three-dimensional figure in that film seemed to bode well for this one. Additionally, he had assembled a superb cast: Moritz Bleibtreu, who was so good in Run Lola Run (Lola Rennt), for the key role of Andreas Baader; Martina Gedeck, who was similarly good in The Lives of Others (Das Leben des Anderen), which looked back at East Germans’ lives under constant state surveillance, for Ulrike Meinhof; and Bruno Ganz, who unforgettably played Hitler in Downfall, as a policeman chasing them down.

On paper, it seemed like it couldn’t miss.

So what went wrong?

It’s not that The Baader Meinhof Complex is a bad film. It’s just that it’s not particularly good, either.

Now, don’t get me wrong. It’s competently made. It tells the story of the rise and fall of the RAF effectively, from a factual perspective. As a period piece — a recreation of Germany in the early ’70s — it’s simply gorgeous. And that last bit is important — much of the power of the RAF came from the aura of “radical chic” that surrounded it, so any telling of its story has to communicate how a scraggly group of angry terrorists could also be so dangerously cool.

Where The Baader Meinhof Complex falls down is somewhere deeper: it doesn’t know what story it wants to tell.

When it starts, it seems to be building its story around the character of Ulrike Meinhof. We see Meinhof — an established, establishment journalist, sort-of-happily married, who publishes vaguely leftist articles of the kind that can be read aloud at black-tie dinner parties to polite applause — respond to an impending visit to West Germany by the Shah of Iran by writing in protest of the Shah’s treatment of his people. When the Shah actually arrives, he is met by placard-wielding protesters, whom the German police brutally crack down upon; at the climax of the violence, one demonstrator is shot dead by an undercover policeman in cold blood.

(The film doesn’t dwell on his identity, but the murdered man was a student named Benno Ohnesorg, and after the Cold War ended it was revealed that the policeman who killed him was secretly an agent for Communist East Germany — leading to speculation that the murder was deliberately intended to inflame the situation in the democratic West.)

These riots, and the merciless police response to them — along with an assassination attempt on a leftist student leader and the collapse of her marriage — lead Meinhof to begin to question her bourgeois assumptions. She starts to wonder if writing articles in fashionable magazines will ever lead to meaningful change in society. Then she goes to cover the trial of a pair of young arsonists — Andreas Baader and his girlfriend, Gudrun Ensslin, who had burned down a department store in a muddled protest against capitalist materialism — and finds a new direction in their commitment to direct, violent action, compared to which her own muddy liberalism seems wanting. (As do her mousy, bookish personality and bourgeois commitment to marriage and children, when placed next to Baader and Ensslin’s wild charisma and swinging sexuality.) Falling under their spell, she gradually goes from fellow-traveler to full-fledged terrorist herself.

This is an interesting story, and the dynamic between Baader, Ensslin and Meinhof has lots of drama in it. Although the RAF came to be known colloquially as the “Baader-Meinhof gang,” in the movie’s telling, it was Ensslin who was the real shaper of its ideology and tactics; Meinhof’s middle-class background made her a more effective spokesperson than terrorist, and Baader was motivated more by an anti-social personality and desire for cheap thrills than by politics.

But at some point, the movie decides it doesn’t want to be about Meinhof after all; it wants instead to be a comprehensive history of the RAF. And the problem there is that much of the RAF’s later history happened after Baader, Ensslin and Meinhof had all been rounded up and locked away in prison, driven by angry young people who barely (if at all) knew them taking up the RAF “brand” in their absence. So we spend the second half of the movie cutting awkwardly between scenes of RAF attacks being planned and carried out by characters we don’t know or recognize, while the characters we do know — Baader, Ensslin and Meinhof — sit in maximum-security cells, arguing with each other as events beyond their control swirl outside.

These two stories running alongside each other are then further complicated by the introduction of a third story, that of Ganz mobilizing all the resources of the national police to defeat the RAF. He’s effective enough in the role, but it never connects properly with the other two stories; his character is too senior to be out in the field confronting the RAF directly, so we get lots of scenes set around conference tables with people debating how to respond to the terrorists. This might be an accurate depiction of how things were at high levels of government, but as a storytelling device, it’s weak. The audience would be better served by following a cop dealing with the RAF’s grisly terror campaigns on the street, even if that character was a composite of many real people. Heck, you can see how that story — a cop trying to bring down a terror cell that many members of the public sympathize with — could be a movie all by itself.

By trying to jam all these stories together, The Baader Meinhof Complex ends up feeling like a bit of an overstuffed sandwich, rather than a cohesive narrative. The cast give good performances, but they’re let down by the script, which would have been better had it picked one story and stuck with it. Which takes a film that should have been spectacular and turns it instead into a bit of a missed opportunity.

(The poster sure is a knockout, though.)