Cities die, too

So I’m clicking around Reddit this evening looking for something interesting to read, and I find a link to an article about the dynamics of creativity from a publication called Greater Good, out of UC Berkeley. It’s an interview with author Jonah Lehrer, who’s just written a book on the subject called Imagine: How Creativity Works.

I haven’t read Mr. Lehrer’s book, but I sure as hell hope the arguments he makes there are more compelling than the ones he gave this interviewer. Because by the end of the interview I was goggle-eyed in disbelief at some of the things he was saying.

The first half of the interview isn’t so bad — there’s lots of hand-wavy, citation-less assertions, but that’s (unfortunately) par for the course in pop science writing, so I can live with it. But then the interview nears its end and Lehrer, apparently afraid to leave without making a Big Impression, guns his engines and jumps over credibility like Evel Knievel over Snake River Canyon.

Vroom!

Geoffrey West, a researcher I interviewed for the book, asks provocative questions about the differences between cities and companies. They look similar from a certain perspective, but they’re also quite different. Cities never die. Cities are immortal. You can have a devastating earthquake like San Francisco did in 1906—but the city is still here. You can nuke a city—it comes back. You flood a city—it comes back.

OK, point number one: cities are not “immortal.” Anyone with a sense of history knows that they die all the time. Sudden disasters like earthquakes and floods tend not to kill them, because if the underlying economics of the area are solid, people will spend the money to rebuild the buildings and drain the floodwaters. But if those economics are shaky, there’s no guarantees that people will decide rebuilding is worth the money. (Anyone from New Orleans can explain to you how this is decidedly not theoretical.)

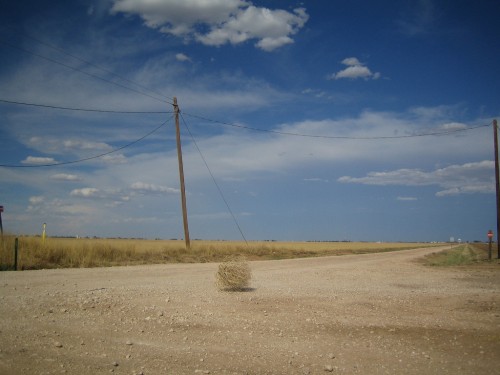

And cities can die even without suffering an external shock, just from the slow action of broad forces. Commercial and demographic tides ebb and flow, making yesterday’s capital tomorrow’s ruin; there’s not much creativity going on right now in Chichen Itza, or Leptis Magna, or Cahokia. And you don’t have to look back centuries to see it happen, either. There’s ghost towns all over the United States that used to be thriving settlements until the silver ran out or the canal shut down or the highway passed them by.

It may look like cities don’t die, but I would argue that’s due to a flaw in the way we as humans observe these things: we tend to miss changes that develop over a timespan longer than our own life. Take Rochester, New York, for instance. Rochester existed when I was born, and I don’t doubt it will exist when I die. But the population of Rochester has been declining for fifty years now; the 2010 Census found the city with a lower population than it had in 1910.

What will Rochester look like in 2110, or 2210? There’s no way to know. It may turn things around and start growing again — much of the city’s growth in the first half of the 20th century was driven by the growth of hometown businesses like Kodak and Xerox that became synonymous with the industrial economy, and it’s not inconceivable that some future business cycle could put Rochester on the upswing again. But assume for a moment that the trend continues in a straight line of slow decline. It’s likely in that scenario that there will be an incorporated jurisdiction of some type in upstate New York named “Rochester” for a long time, even as the area hemorrhages residents, but that’s a far cry from the spirit of the Unkillable City that Lehrer conjures up.

Which brings me to Lehrer’s next point:

But companies die all the time. The average lifetime of a Fortune 100 company is 45 years. Twenty-five percent of Fortune 500 companies die every decade. Only two companies in the original Dow Jones still exist.

So why do companies die while cities live forever? What’s the difference? And what does that tell us about creativity?

Lehrer again turns to West for his answer:

Geoffrey West found that as a city gets bigger, everyone in that city becomes more productive. They invent more patents, make more trademarks, make more money, and so on. As companies get bigger, the opposite happens. Everyone in the company becomes less productive. There are fewer patents and fewer profits per employee.

In the end, this makes companies very vulnerable. Wall Streets says, “Get bigger! Get bigger!” Then they have this big expensive bureaucracy to maintain and they become more aligned with their old ideas. They’ve got to invest lots of money in expensive new acquisitions and sometimes those acquisitions don’t work out. Eventually their old ideas are no longer relevant, and they go belly up.

Which, frankly, strikes me as seriously off-base. There is a much simpler explanation for why companies die more frequently than cities: economic diversity.

A city, in other words, is a big, hairy bundle of thousands upon thousands of streams of economic activity, each of which operates independently of most of the others. If a major corporation sets up its headquarters in the city, it brings with it a large number of new economic streams, but the city is by definition bigger than the corporation; its lifeblood comes not just from the new HQ, but from all the other economic actors in the city as well — taxicabs and delis, condos and dry cleaners, as well as all the operations of all the other corporations in town.

This is important, because it means that a city is not an economic monoculture, and that means that if the economic environment changes — if a line of business that used to be reliably profitable suddenly becomes less so — the city’s overall economic rationale can not disappear overnight. Which isn’t to say that it can’t disappear — as we discussed above, it certainly can — but that process takes time to operate, as the ripple effects spread through the local economy. A major change in the economic climate can take decades to fully shake itself out. And that time buffer is what makes cities resilient; it gives their residents time to adapt, to create new economic streams to replace the old ones. Sometimes that works out, sometimes it doesn’t, but cities at least have the chance.

Corporations, on the other hand, generally do not. A corporation is an economic monoculture; the rationale for its existence is premised on a single set of economic facts. If those facts change dramatically — if the price of a key input goes up, or public tastes change, or a process previously thought harmless is discovered to have health-threatening side effects — it’s entirely possible for a business that looked economically sound yesterday to suddenly look unsound today. And once a business stops looking economically sound, it doesn’t take long for people (customers, partners, investors, creditors, etc.) to start pulling their money away from it.

(It’s worth noting that cities aren’t necessarily economically diverse, and corporations aren’t necessarily economic monocultures. “Company towns” whose economy is tied to a single key business or industry, for instance, certainly exist; think of Detroit and the domestic auto industry. But that’s an exception that proves the rule; if you make your city more of an economic monoculture, you open it up to the same risks that other economic monocultures run.)

So what does all this have to do with creativity? I’m honestly not sure. I haven’t read Geoffrey West’s research, so I’m just going on how Lehrer characterizes it, but at this level, at least, it seems contrived.

But that could just be me not being sufficiently creative, I guess.

Comments

Aunt Rooney

April 17, 2012

3:37 pm

And your very hometown is declining, too. Houses are abandoned… no jobs as production is being shipped overseas… and not outsourcing customer service by one of our largest employers is creating another vacuum.

You are correct it is pop science and not founded in any empirical evidence.

Great thoughts, Jason! Keep them coming!

Jason Lefkowitz

April 17, 2012

10:06 pm

Yup. It’s true all over the upper Midwest… fingers crossed that someone can figure out how to turn things around.

Ben Withman

April 19, 2012

6:20 pm

Dead cities can be worth money, though. Ghost town Scenic, SD was bought by a Filipino church for $700,000 and Buford Wyoming, pop. 1, was bought by a Vietnamese investor for $900,000, and ghost town Henry river, NC, which was in The Hunger Games is on sale for $1,400,000. Also, Montgomery County, OH has actually increased in population since the 2010 census.