Playing Machiavelli in the Middle East in “Conflict: Middle East Political Simulator”

As long as I’m on a kick of writing about old DOS strategy games too good to be left languishing in abandonware limbo, I’ll throw in one more: 1990’s Conflict: Middle East Political Simulator.

Conflict MEPS: Title screen

Conflict took the wrenching, intractable problems of the modern Middle East and turned them into a cracking little strategy game.

The basic premise was simple. You, the player, start the game as a newly-elected Prime Minister of Israel in the distant future of 1997 (!). In this role, you have to guide your country in its relations with the other nations of the region, particularly those which share a land border with Israel — Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt.

Your goal: to bring down the governments of all four of those states.

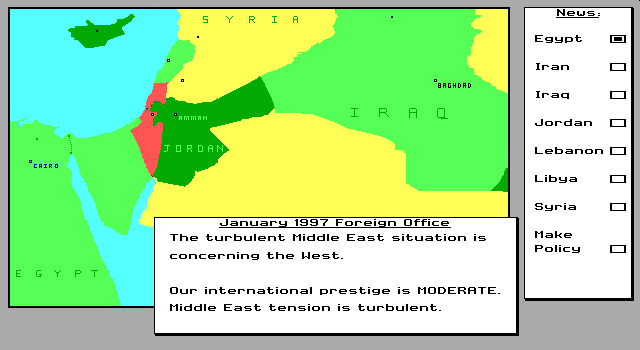

Conflict MEPS: User interface

As you may have deduced from the description above, Conflict‘s worldview is unapologetically driven by Realpolitik. There is no room in this game for peaceful co-existence between Israel and its neighbors; they may get along for a time, but that is generally only to provide a breathing space in which they can rest and re-arm before going for the jugular once again. The smiles and handshakes only last until one side or the other feels strong again; then the tanks and fighter-bombers come out.

As PM, you have three basic sets of tools at your disposal for dealing with your neighbors:

- Diplomatic: You have diplomatic relationships with all the region’s nations; not just your immediate neighbors, but also more distant countries like Libya, Iraq and Iran. You can use these relationships to make friendly or hostile overtures, with the hopes of improving your relationship if you don’t want to fight that country just yet or souring it if you do.

- Covert: You also have relationships with various “opposition parties” in each country. (I put “opposition parties” in scare quotes there, because it’s not like these groups are out to win any elections. They want to overthrow the goverment and take control of it for themselves.) Few of these groups are strong enough to directly challenge their nation’s government on their own. However, with sufficient supplies of Israeli arms and cash, who knows?

- Military: A big part of your responsibility as PM is managing the size and disposition of Israel’s military resources. Israel is a small nation, with a small military budget; you can only afford to buy so many M1 Abrams tanks or F-111 fighter bombers per month, making building up your military a long-term process. And a war with one of the big regional powers like Egypt or Syria can burn through all that hardware fast. Still, in a dangerous world, having a strong military is a sound investment; and when it comes to toppling your neighbors, invading them and seizing their capital city is the gold standard.

The strategy of the game comes in how you balance each of these factors month by month in your relations with other nations in the region. Maybe you notice Lebanon has become unstable all on its own, so you choose to just maintain friendly diplomatic relations with their government while quietly arming the opposition. But meanwhile, Syria has started building up its tank forces, so you start investing in anti-tank helicopters so you’re ready in case they make a move against you; but that means Egypt, with whom you have friendly relations, sees you building up your own forces and starts to wonder if you’re the one with designs against them, so they start their own military expansion, just in case…

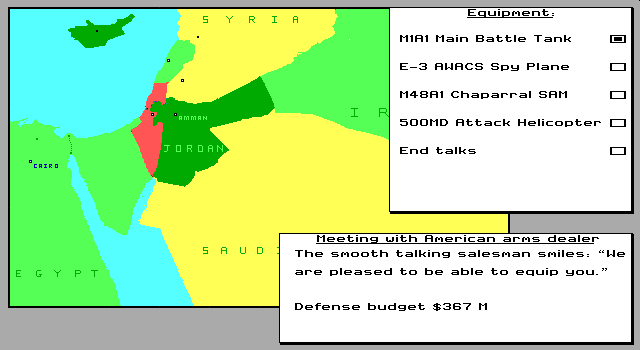

Conflict MEPS: Give the gift of tanks

Beyond the three core gameplay elements above, the game also throws in some additional mechanics to liven things up and keep them interesting. Weapons, for instance, can be purchased from any of four sources — the U.S., the U.S.S.R, Britain, and France — and none of these vendors will offer you the really good stuff at the outset; you have to demonstrate you’re a good customer by buying plenty of their bargain-bin items first. And of course, buying from one vendor can affect your relations with the others; if you spend years buying nothing but Russian hardware, the Americans and British will eventually shut you out of their marketplaces, and vice versa. (The French, on the other hand, will happily trade with anyone.) This can make life difficult if, say, your primary source of weapons decides that your invasion of Jordan is unjustifiable and hits you with an arms embargo.

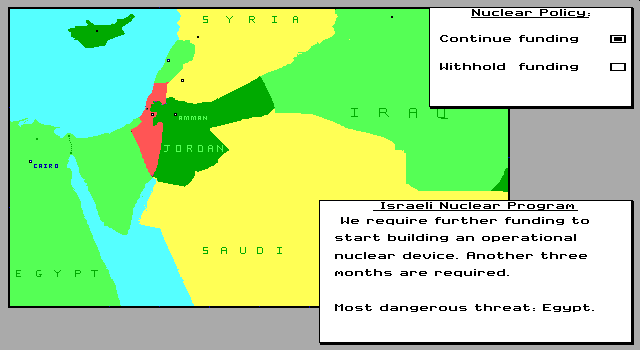

Conflict MEPS: Nuke shopping

The game also lets you invest, if you wish, in a program to develop nuclear weapons. These programs are expensive, and can take years to show results — a long time in a game where each turn is a month long. And money you funnel towards nukes is money you can’t spend on conventional weapons, which weakens your military posture. But if you manage to actually build one, your position in the game changes overnight — nobody’s going to invade a country with nuclear weapons. Except a country with nuclear weapons of its own, of course. And your opponents can invest in their own nuclear programs, just as you can. If your intelligence services spot another country working on a nuke program, you can use your air force to try and bomb it out of existence before it bears fruit, a la Operation Opera. But the success of such a raid is not guaranteed, and a failed raid can leave you with a furious neighbor on the verge of having its own nuclear arsenal. (And, of course, your neighbors can try to bomb your reactors, too.)

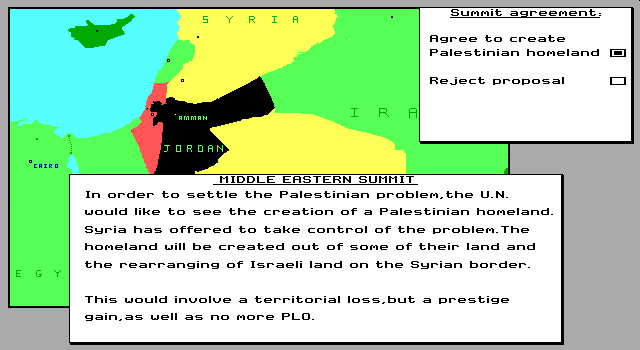

Conflict MEPS: Fine, here’s your freaking homeland

Meanwhile, while all of this is going on, you have to deal with the Palestinians and the United Nations as well. The “Palestinian Problem” will periodically flare up, requiring deployment of troops in the West Bank to tamp it down — troops who thus can’t be available to defend your borders or fight your wars. And the U.N. constantly wants you to sign agreements to limit the size of your military and make concessions to the Palestinians — agreements that can buy you better relations with the world, but at the cost of reducing your freedom of action in the region.

The beauty of Conflict is the way a simple design and set of rules interact to create real, compelling stories each time you play. Maybe in one game you build up a public image as a man of peace, giving the Palestinians their homeland and conspicuously abstaining from military action, while quietly overthrowing all your neighbors via covert action. In another, you might find yourself locked in a stalemated, years-long war with Egypt, only to be delivered just before your own government falls by a sudden invasion of your enemy by the Libyans. Or maybe you’re the PM whose nuclear ambitions drive an atomic arms race that ends with every capital in the region a pile of radioactive ash. Each game provides a different experience, a different story.

Which isn’t to say that Conflict is perfect. Like most games of its era, its interface can be opaque and hard to learn at first, though unlike many of its peers it at least provides colorful graphics and an interface that works equally well with keyboard or mouse. And its design is obviously highly stylized, meaning that it provides more of a Middle Eastern-flavored Machiavellian fantasy than an educational look as the region as it actually is or was.

Still, it plays fast, offers lots of interesting choices, and is generally a blast to play. It’s a game I still play today, 25 years after my father bought a copy for me to play on a computer that had less processing power than the smartphone in your pocket. That’s the true test of a game design — the technology used to implement it may age and fade, but does the design itself stay compelling? Conflict did, and does.

UPDATE (November 7, 2019): Thanks to the wizards at the Internet Archive, you can now play Conflict: Middle East Political Simulator right in your Web browser.