Better know an apocalypse: South China Sea edition

We here in the United States are in the middle of an election season, which means that our attention at the moment is focused like a laser beam on domestic problems. But the world doesn’t stop turning just because we’re not paying attention, and over the last year we’ve drifted closer to conflict with a range of other major powers than we’ve been in a long time. So this is the first post in an occasional series, “Better Know an Apocalypse,” whose purpose is to bring you up to to speed on these potentially catastrophic flashpoints.

We here in the United States are in the middle of an election season, which means that our attention at the moment is focused like a laser beam on domestic problems. But the world doesn’t stop turning just because we’re not paying attention, and over the last year we’ve drifted closer to conflict with a range of other major powers than we’ve been in a long time. So this is the first post in an occasional series, “Better Know an Apocalypse,” whose purpose is to bring you up to to speed on these potentially catastrophic flashpoints.

Today’s flashpoint: the South China Sea!

Where it is

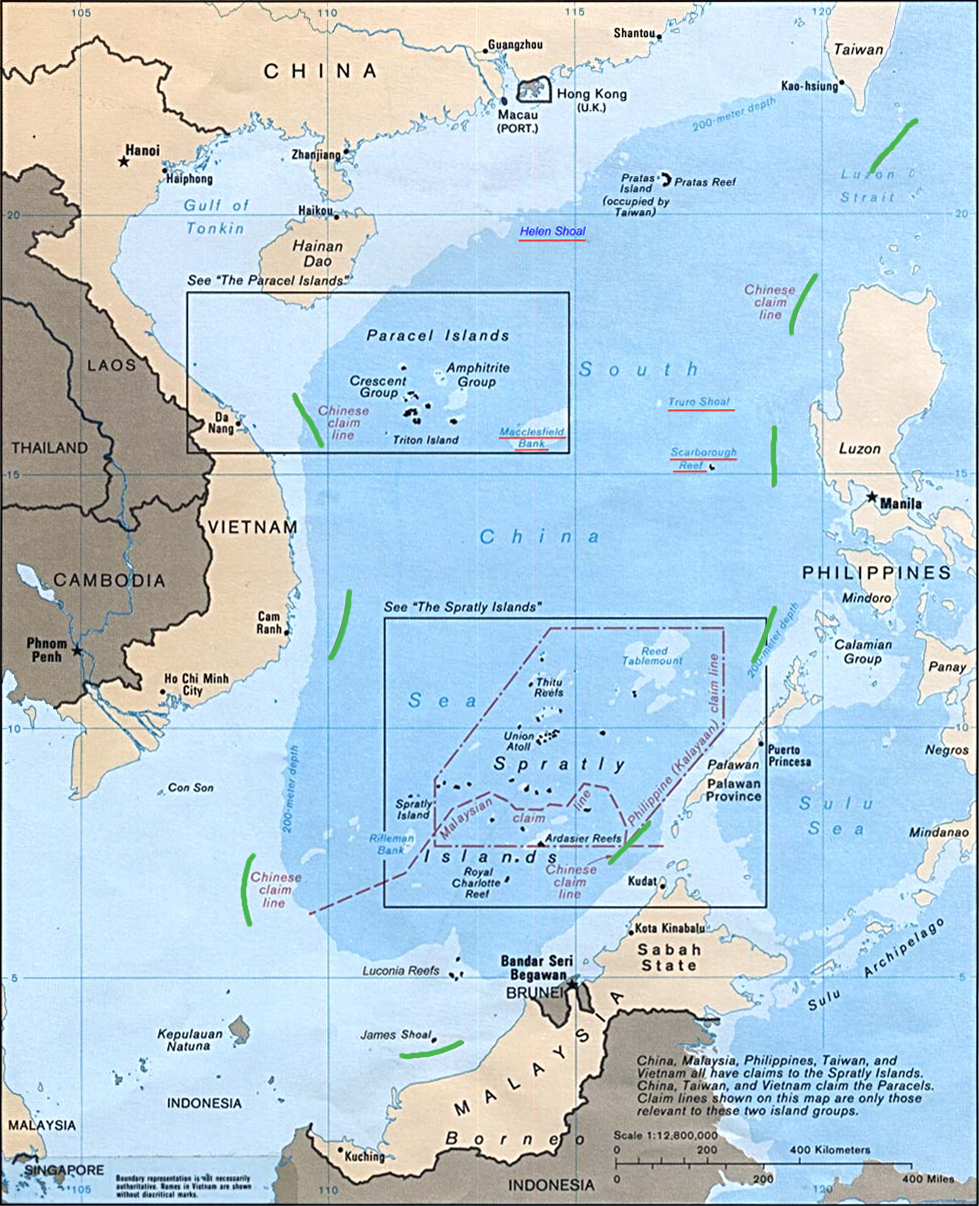

Part of the western Pacific Rim, the South China Sea comprises the waters off the coasts of the nations of Southeast Asia. Roughly speaking, it can be defined as those waters south of China and Taiwan, west of the Philippines, north of Indonesia and Malaysia, and east of Vietnam.

Who’s quarreling over it

China on one side, and just about everybody else in the region plus the United States on the other.

Why it matters

Access to the South China Sea is critical to the economic interests of the United States. By volume of goods traded, Taiwan is the US’ 11th biggest trading partner, Vietnam 13th, Malaysia 14th, Indonesia 20th, the Philippines 30th. Nearly all of those goods are transported back and forth by container ship, which means that access to the South China Sea is critical for these trade relationships to function.

China, of course, has major economic interests in the region as well. With a long coastline running directly along the South China Sea, it is critical to the ability of her own burgeoning economy to be able to import raw materials and export goods. Additionally, the Chinese economy is increasingly dependent on imported oil, and the roughly two-thirds of its imported oil that it acquires from Middle Eastern and African sources passes through the South China Sea on its way to Chinese ports.

Also relevant to China’s oil needs is the belief held by some that substantial untapped oil reserves exist under the South China Sea itself. If the South China Sea proves to be a fertile place to drill for oil, and China has exclusive control over resources found in the region, it could reduce her need to import oil from abroad.

What’s in dispute

The basic issue is the question of where exactly the territorial waters of the nations around it end and where international waters begin.

What’s the difference, you ask? It’s a distinction designed to answer an obvious question. On land, national borders tell us where a particular nation’s laws apply. But what tells us that at sea? Once we leave shore, how do we know where one nation’s laws end and another’s begin?

In the modern world, the generally accepted answer is that a nation’s laws only apply in their territorial waters, which are defined as those waters that begin at their shoreline and extend out 12 miles from there. (Borders drawn on land are extended out to sea in a straight line, to avoid situations where Country A’s beach is lapped by waters legally controlled by Country B.) Within those waters, the laws of the each nation are in effect every bit as much as they are on land.

Once you get out past the 12-mile limit, though, that stops being the case. There can be situations where a nation has a limited set of rights outside its territorial waters. (An example is an exclusive economic zone, where international law has granted a nation a monopoly on exploiting particular oceanic resources like fish, water or wind.) But generally speaking, everything outside the 12-mile limit is held to be international waters — a region outside the realm of the laws of nations, governed instead by the much more limited law of the sea.

The heart of the dispute is that, when it comes to the South China Sea, China disputes that its territorial waters end 12 miles out from its shoreline. Instead, the Chinese government asserts that its territorial waters reach out to include nearly all of the South China Sea itself — an expansive claim that has come to be known as “the nine-dash line,” after the markings Chinese maps use to enclose the claimed area.

An international tribunal in the Hague rejected China’s claims in the region in July, but as of this writing the Chinese have not retracted them.

The dispute, therefore, boils down to this: who controls the terms under which ships transit and resources are extracted from the South China Sea? Are these international waters, essentially open to all comers? Or are they Chinese waters, with the Chinese government having claim on their resources and determining who can or cannot pass?

What’s causing conflict

China making sweeping territorial claims in this region is not a new development — the People’s Republic of China has held that it possesses everything within the nine-dash line ever since it took over mainland China in 1949. What is new, however, is China being willing to expend resources and political power to back up those claims with diplomatic and military force.

Poor and surrounded by enemies, the Chinese Communist state spent most of its history focused on the Asian mainland, with relatively little interest in asserting herself at sea. As she has risen into the first rank of world powers, however, that has begun to change. Major investments have been made in expanding the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), including expansion into “blue-water navy” functions like carrier aviation that the PLAN has in the past eschewed.

Beyond building ships, China is also bolstering her claims that the entire “nine-dash line” is Chinese territory by creating new Chinese territory within it. Starting in 2014, she began dredging sand onto coral reefs in two island chains in the region — the Paracel Islands in the northwest, and the Spratly Islands in the south — to create new, artificial islands in each. (One U.S. admiral dubbed this project “the Great Wall of Sand.“)

These islands threaten the interests of other nations in the region, along with the U.S., in two ways. First, if there really is a substantial amount of oil to be tapped under the sea there, they could in theory allow China to claim that her territorial waters now extend out 12 miles from the shorelines of each of the new islands, rather than from the shore of the Chinese mainland. Given the position of the Spratly and Paracel island chains, this would create a legal rationale for the “nine-dash line” claim that had not existed in the past — which, if accepted, would allow her to cut the other nations in the region out of that potential oil bonanza.

Second, if push were to come to shove, those islands could also provide convenient bases for Chinese military aircraft, along with anti-ship and anti-aircraft missiles. Such a network of bases could in theory permit China to simply throw legality aside and declare de facto control over the region, and any power that wanted to challenge the claim would then have to face the prospect of going to war with China to do so.

A war with China would be a fearsome prospect for any nation, even the United States, whose military position in the region is not terrific. And a war between China and the U.S. would be a war with nuclear-armed powers on both sides, which could spiral out of control very quickly even if both nations intend at the outset to keep it limited.

What happens next

As noted above, as of this writing China is continuing to press its claims in the region despite international disapproval, so it doesn’t appear that the conflict will de-escalate on its own any time soon.

The Chinese claims are prompting many nations in the region to escalate their military spending, both to deter any theoretical aggression and to put them in a better position if that aggression stops being theoretical. Vietnam is estimated to have quadrupled its annual military spending over the last decade, and the government of nearby Japan is seeking to expand its own forces as well.

The United States has been working to pull the various nations in the region challenged by China’s claims into a more closely-knit, unified opposition. President Obama visited Vietnam earlier this year, in part to further this process.

That effort was dealt a blow in May, however, when the people of the Philippines elected a new president. Rodrigo Duterte is best known internationally for the draconian crackdown on crime he has launched — a crackdown that has claimed nearly 2,000 lives in just sixty days — but in foreign policy he has positioned himself as open to a rapprochement with China, including having the Philippines settle their territorial disputes with China one-on-one rather than as part of a broader, U.S.-oriented regional bloc.