We did it, all by ourselves

So I stumbled across this documentary on Netflix yesterday called Holy Hell, which isn’t bad. (If not as great as some of the critical buzz would suggest.)

Holy Hell is the work of a filmmaker named Will Allen, who after graduating from film school in the mid-80s wandered into the orbit of a group of charismatic young people who called themselves “the Buddhafield.” Led by an eccentric guru and former actor named Michel, the Buddhafield sought enlightenment through a very California combination of meditation, physical fitness and contemporary ballet. (Yes! You did in fact read that correctly!) Intrigued by their sunny spirituality, Allen joined them. He wouldn’t leave for 22 years.

Allen’s film-school background and cinematic ambitions led Michel to appoint him as the group’s in-house filmmaker; much of Holy Hell is drawn from the enormous amount of footage he shot over his two decades documenting the life of the Buddhafield. And as soon as you start watching that footage, which focuses like a laser on the person of Michel, you realize where the story is going: the Buddhafield is going to become a cult.

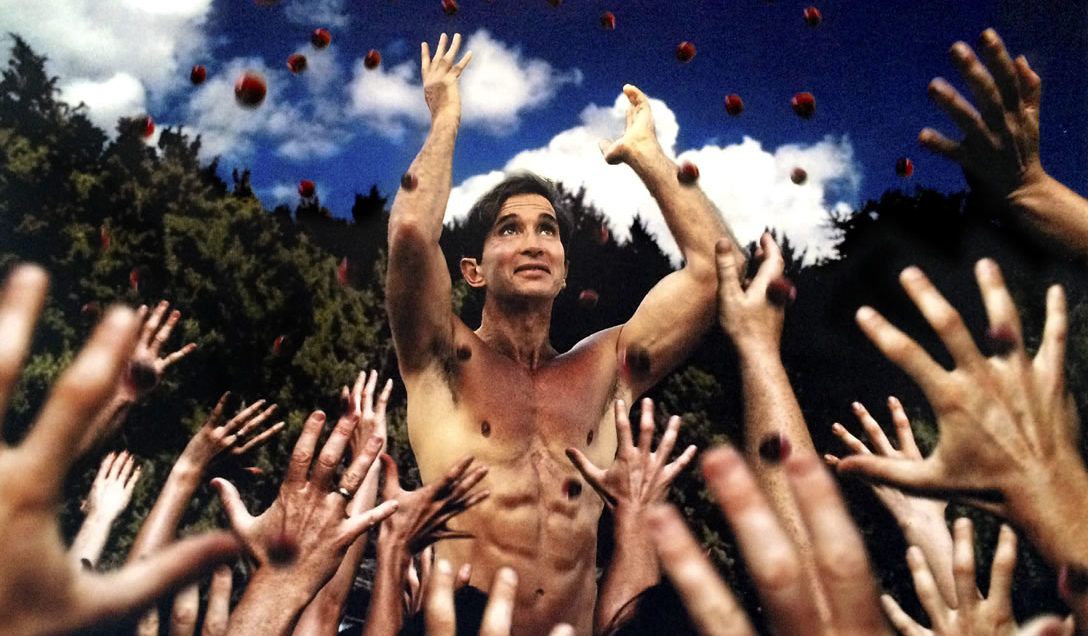

I have a kind of fascination with cults — or maybe with what William James called “the varieties of religious experience.” Not least because they tend to an outsider to look very silly. It’s easy to laugh at the true believers of the Buddhafield for dedicating their lives to a personage like Michel, who appears (to our outsiders’ eyes) completely ridiculous: a fey New Age Yoda, spouting watered-down Buddhism while clad in nothing but Ray-Bans and a banana hammock.

But they’re not alone in this kind of thing, after all. They’ve disengaged their critical faculties, certainly, but then billions of people do that while contemplating more mainstream prophets every day. Disengaging your critical faculties is sort of what faith is all about.

So what’s interesting about cults isn’t generally their members, who are just human beings responding to a need that’s as old as humanity itself. What’s interesting about cults is their leaders — or, more accurately, what being on the receiving end of all that faith does to them. Because human beings just aren’t wired to handle that sort of thing gracefully.

You can see that dynamic in action in Holy Hell. The ideology of the Buddhafield is built around service, and early on we see that being interpreted broadly, as the members work to serve both each other and the community at large. But as Michel’s following grows, the message changes; it becomes less about serving others and more and more about serving Michel. Devotees we saw in the early days of the cult cooking meals for each other and helping local quadriplegics with their daily chores show up later weeding Michel’s garden, carrying an ersatz throne for Michel to sit on, even building an entire dance hall for Michel to perform in. He stops being a messenger of veneration and instead becomes its object.

And then his demands get really personal, and things take a turn that is both disturbing and completely, utterly predictable.

I felt for the members of the Buddhafield, because I understand why put themselves in the position they did. I feel the same drive they did; I would love to have a spiritual teacher, someone who could help me understand why the world is the way it is. But while I’ve run into a fair few people who put themselves forward in that role, what I have yet to find is one who seemed worthy of being followed.

Prophets are easy to find, if you don’t care whether they are false. It gets much harder if you do.

So what would a real leader look like? I think the key is in the word I used above. Not a prophet, not a guru, but a teacher. Someone whose interest in her students is what she can do to improve the students, rather than in what the students can do to improve her.

A leader who starts by following.

I wrote a bit in this space recently about my fondness for Stephen Mitchell’s translation of the Tao Te Ching. A quote from that work on this subject has stuck with me ever since I first read it.

The Master doesn’t talk, he acts.

When his work is done,

the people say, “Amazing:

we did it, all by ourselves!”

Amazing.