All the little Harveys

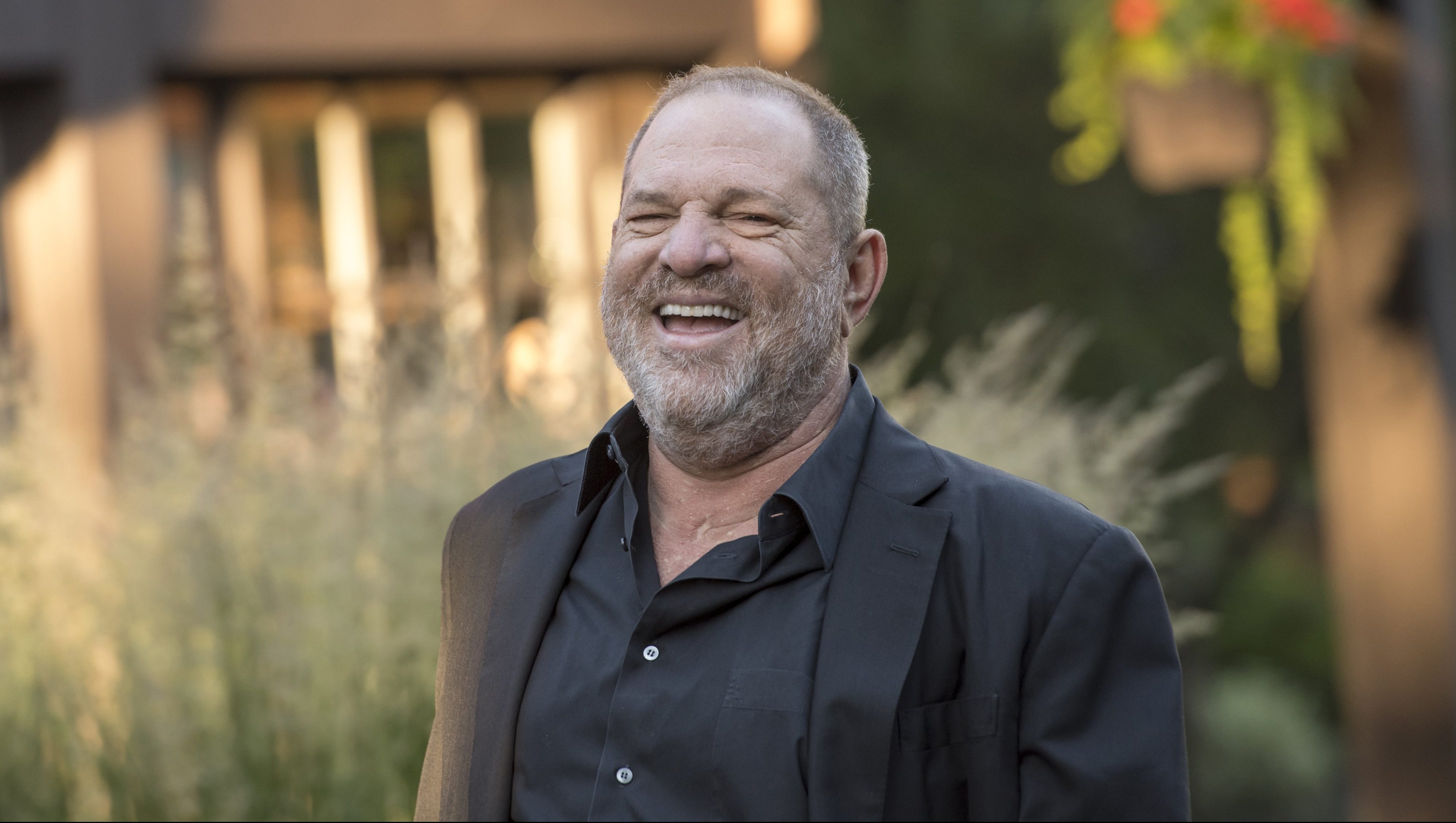

Harvey Weinstein arrives for a morning session during the Allen & Co. Media and Technology conference in Sun Valley, Idaho, U.S., on Wednesday, July 12, 2017. Photo credit: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg.

The big news over the last couple of weeks has been the spectacular downfall of movie producer and Hollywood player Harvey Weinstein, after the New York Times revealed that he had been sexually assaulting women for decades and using his money and power to cover it up. That story opened a floodgate, as dozens of women, including such famous actresses as Ashley Judd, Gwyneth Paltrow and Angelina Jolie, came forward one by one to recount their personal experience of being molested by Mr. Weinstein. (As of today, more than 40 women have reported such assaults.)

The reaction was swift — Weinstein’s wife has left him, he has been fired from the production company he co-founded, and he has been expelled from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the Producers Guild of America. Even if he never faces any legal consequences for his loathsome actions, his career, reputation and family all lie in ruins, which seems only fair given the pain he inflicted on so many for so long.

So: good riddance to bad rubbish.

But, while it’s satisfying to see Weinstein finally reap what he has sown, I worry that the focus on him is obscuring the deeper crisis he represents. Because the problem isn’t one rich, powerful man using his money and power to abuse women for his own gratification. The problem is that there are lots of men doing that.

Just keeping our eyes on the entertainment industry, for instance, the last few months has seen the exposure of many other offenders besides Weinstein:

- Roy Price, head of Amazon Studios, lost his job after charges emerged both of him harassing women personally and of his moving forward with deals with others after being informed that those others had assaulted women

- Devin Faraci, movie critic and blogger, lost his job as editor-in-chief at Birth.Movies.Death after a woman accused him of sexually assaulting her, and was dropped from a new gig with trendy theater chain Alamo Drafthouse a year later after a wave of disgusted Drafthouse customers protested his hiring

- Harry Knowles, founder of the pioneering movie blog Ain’t It Cool News, took a “leave of absence” from AICN after five women came forward to accuse him of sexually assaulting them during his tenure with the site

- Gilbert Rozon, founder of the famous Montreal comedy festival Just For Laughs, quit the festival this week amid allegations from nine women of sexual abuse and assault spanning three decades

And these men are not the only ones, of course. There are some we already know about, like Bill Cosby. There are others who, the way Cosby used to be, are followed around by persistent but so-far unproven rumors, like Louis C.K. And there others whose names we’ll never know, uncountable small-timers who aren’t famous enough for their crimes to make the news, little men with little hearts who used what little power they could claim to force women to bend to their will.

There’s a bright red thread running through all these stories, too. Inevitably, when the truth about the disgraced man finally comes out, other men start coming forward and admitting that they knew what was going on. Maybe not knew knew, as inevitably it was never explicitly discussed; but everyone around the predator understood that he was periodically going to make some new woman among them his prey, leaping upon her and dragging her off into the underbrush. None of them followed, of course; they didn’t want to know too much about the gory details of what happened after that. But in a general sense, they knew.

Everybody knows what predators do with their prey.

Some might argue that this epidemic is specific to the entertainment industry, but I have trouble believing that. We have a President who proudly bragged of using his power to get away with assaulting women, after all, along with an ex-President who spent his entire career dodging allegations of sexual abuse. It’s hard to argue that either of them is Hollywood’s fault.

What’s happening here, I think, is different. And I think what’s happening in Hollywood is the proverbial canary in the coal mine — a preview of what we’re going to be seeing in lots of industries, lots of communities, all across America.

One of the reasons harassers get away with it so often is that their victims feel isolated; they fear that, if they do go public and report their attacker, nobody around them will believe them. And for a long time that has been true, because the faces those victims saw when they looked around were overwhelmingly male. They feared that, when the crunch came, the men who lived behind those faces would choose to believe their attacker instead of them, simply because the attacker was a man too. That men would stick together, regardless of how much evidence piled up.

This may seem like a dim view for these women to take of men. But it turns out that it was absolutely correct! In case after case after case, after the predator is unmasked we meet all the men around him who knew what was going on and chose to do nothing. Every Harvey Weinstein turns out to have his entourage of Scott Rosenbergs and Quentin Tarantinos and Kevin Smiths, of men who became masters at the art of averting their eyes. They all have their own excuses, of course — It was her word against his! He had power over my career, too! He never victimized any women I knew personally! — and after the unmasking we get to listen to them all, ringing hollowly, too little and too late all at once.

What’s different now is that, when women in entertainment look around themselves today, fewer of those faces belong to those men and more belong to other women — many in positions of real power. Women have been making inroads into all avenues of American business for decades now, but the entertainment business opened up to them earlier than most. (Mary Pickford was a co-founder of United Artists in 1919; the first woman president of a Hollywood studio, Sherry Lansing, was hired in 1980.) So the professional network of women working in entertainment has been growing for longer than the comparable networks in most industries.

We’re seeing now, in other words, a maturation of that network; a collective statement that women have finally achieved enough power in entertainment to not have to put up with the Weinstein treatment anymore. The women in that network know how many of the others, unlike their male colleagues, have suffered quietly through similar experiences of their own.

They know that finally there are people around them, people who matter, who will believe them.

(It’s worth noting here that of the three reporters most associated with breaking the Weinstein story, the two from the Times, Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, are both women.)

But that’s entertainment. In lots of other industries, women in positions of power are still rare, still exceptional, still isolated. But there’s lots of women farther down in all those industries, working diligently, moving forward. What happens when the networks of women in those industries become as robust and confident and powerful as the network of women in entertainment?

I think what will happen is this: we will discover that America’s workplaces are, and have been for a long time, full of little Harveys. That in all kinds of industries, men with power and money have been using those resources to abuse women they work with — and, more disturbingly, to get away with it. That too many of the men around those predators have chosen to let them run wild, to not rock the boat, to take the easy dollar and keep their mouths shut. And that generations of working women in all walks of American life have been suffering silently, burying their stories of abuse down deep, taking them all the way to the grave, for the simple reason that they didn’t think anyone would believe them.

And then, once all the little Harveys and their enablers have finally been forced out into the sunlight, lots of us — especially lots of us men — are going to have some difficult questions to answer.