The Tragedy Of Barack Obama

On the night of November 5, 2008, standing in the crisp autumn air of Chicago’s Grant Park at the end of a long and bitter campaign, President-Elect Barack Obama told America that the hard work was yet to come:

Even as we celebrate tonight, we know the challenges that tomorrow will bring are the greatest of our lifetime – two wars, a planet in peril, the worst financial crisis in a century. Even as we stand here tonight, we know there are brave Americans waking up in the deserts of Iraq and the mountains of Afghanistan to risk their lives for us. There are mothers and fathers who will lie awake after their children fall asleep and wonder how they’ll make the mortgage, or pay their doctors bills, or save enough for college. There is new energy to harness and new jobs to be created; new schools to build and threats to meet and alliances to repair.

The road ahead will be long. Our climb will be steep. We may not get there in one year or even one term, but America – I have never been more hopeful than I am tonight that we will get there. I promise you – we as a people will get there.

Today, nearly two years later, enough Americans wonder if we will, in fact, ever get there that the Republican Party — which teetered on the brink of irrelevance that night when Barack Obama spoke in Grant Park — has surged to unprecedented levels of electoral support.

It’s safe to say that the journey that began that night in Chicago has taken us somewhere very different than President Obama anticipated.

This is not to say that the first two years of the Obama Administration have been without accomplishments. Far from it. And you can sense occasionally in the words of Administration figures their frustration at seeing their support slide away even as they rack up legislative achievements.

During an interview with The Hill in his West Wing office, White House press secretary Robert Gibbs blasted liberal naysayers, whom he said would never regard anything the president did as good enough…

The press secretary dismissed the “professional left” in terms very similar to those used by their opponents on the ideological right, saying, “They will be satisfied when we have Canadian healthcare and we’ve eliminated the Pentagon. That’s not reality.”

Mr. Gibbs’ barbs are aimed at the wrong flank; it’s unlikely that it’s the “professional left” that is seriously weighing voting Republican this fall. And yet, his remarks are important nonetheless, because they contain the key to understanding the disconnect between the Administration’s ambitions and its fortune: the sense that, for his critics, nothing President Barack Obama does is ever good enough.

Why, the Administration wonders, are these people so upset? We’ve done so much! We’ve passed health care reform! Financial reform! A stimulus package! An agenda this ambitious hasn’t been seen in Washington since the days of LBJ! And we passed it!

And it’s true: they have indeed done all these things. But it is also beside the point.

In the final analysis, the measure of a President is not how many programs he passes, or how sweeping those programs are. It’s how those initiatives impact the lives of the American people. The bills and the programs are not the ball game; they are merely the ball.

And while it is true that the Obama agenda has been legislatively ambitious, it has also been, in practical terms, invisible to people outside Washington, D.C. A stimulus was passed, true; but it was so severely gimped that it barely dented the unemployment rate. Health reform was passed, true; but the parts that will touch most peoples’ lives won’t take effect until 2014. Financial reform was passed, true; but the “too big to fail” banks that dragged us into financial crisis managed to pull most of its teeth. And so forth.

Plenty of bills have been passed, in other words; but for the average American, very little has changed in their daily lives. They still live in fear of losing their job or their health insurance. They still struggle under the burden of crushing credit card interest and deceptive fees from their banks. They still see their government run with greater concern for the tender sensibilities of hedge fund billionaires than for the future of the middle class.

They voted for change, but when they look around, there is precious little change to be seen.

Contrast these past two years to the two years after Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office. Unlike Obama, Roosevelt understood that in order to restore confidence in a time of depression, people had to see things around them changing. There had to be unmissable signs that the old days — the days of fear and uncertainty — were really over.

So when Roosevelt set up his First Hundred Days — the brace of legislation that he set about passing immediately upon taking office — it didn’t just include a push for legislation to insure bank depositors wouldn’t lose their savings if the bank collapsed; he closed the banks for a week, to make the point that their business was being well and truly reorganized. It didn’t just include a push for a National Recovery Administration to fight deflation; it urged businesses participating in the NRA’s “fair competition” programs to display a new symbol, the Blue Eagle, to show customers that they were doing their part to turn things around. And Blue Eagles were soon found in shop windows across America.

The point of this comparison isn’t to say that Roosevelt was an unmitigated genius. Plenty of early New Deal projects ended up failing, including the NRA, which was struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935. But by the time that happened, the point had been made; even people who paid no attention to politics whatsoever could see while going about their everyday lives that Roosevelt was taking action, trying things, and in times of crisis Americans prefer a President who tries things and fails to one who appears to be trying nothing at all. And they demonstrated this in the 1934 midterm elections by giving the Democrats an even bigger majority than they had won on Roosevelt’s coattails in 1932.

The irony is this: for all the cries from the Right that Obama is a dangerous radical with revolutionary ambitions, he has led his party into unpopularity by being too cautious — too unwilling to use his power to affect peoples’ lives directly, especially when doing so would risk confrontation with powerful lobbies and entrenched interests.

Now, based on his remarks noted above, I imagine Robert Gibbs would probably say that this criticism is unfair. We weren’t lucky enough to have the Congress FDR had, he’d argue; we had to compromise, had to go for the half loaf, because it was all we could get from them. What we got was the best that could be gotten.

And perhaps that, too, is true. But it, too, is also beside the point.

The reputations of Presidents are not made by one and only one thing: accomplishment. Presidents who get things done are remembered fondly; Presidents who do not, or cannot, are swiftly forgotten.

Is this fair? Maybe, maybe not. But it’s the nature of the job. And Barack Obama wasn’t drafted for this job; he sought it out. He’s a smart, well-educated man; presumably he knew, at least to some degree, what he was getting into.

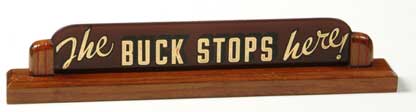

When he was President, Harry Truman had a sign on his desk to remind him of this fact. It read “The Buck Stops Here.”

That’s how our system works. If you want to be President, you have to accept that you will be judged by your accomplishments — not your legislative accomplishments, mind you, but accomplishments that ordinary people can see and feel and hear.

How many lives did you make better, Mr. President? How much suffering did you ameliorate? How many American dreams did you help your people realize? These are the metrics by which a President’s legacy is measured, not how many bills you passed.

This, then, is the tragedy of Barack Obama: he has focused on amassing an impressive portfolio of legislative accomplishments, only to discover that passing all those bills is, by itself, not enough. It has not led to the real-world accomplishments that his Administration and party will be judged on when voters go to the polls in November. And confronted with a situation where they are evaluated by standards that can’t be found in the Congressional Record, they seem lost at sea.

As they consider how to turn that trend around, it might be useful for the President and his advisors to take Truman’s desk sign to heart. The problems they face are only reflected by their critics, not created by them. They have it within their power to turn things around, to change the trajectory of history — or, at least, to make a creditable attempt! — if they want to.

The office where Barack Obama sits is the same one that Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman sat in, after all. Even today, the buck still stops there.