Going All In, Or Emerson In Tahrir Square

I wrote last Friday that the uprising in Egypt appeared to be heading for a moment of decision, with protesters’ calls for that to be President Hosni Mubarak’s “day of departure” set to collide with Mubarak’s gradually increasing use of force to try to back them down.

I wrote last Friday that the uprising in Egypt appeared to be heading for a moment of decision, with protesters’ calls for that to be President Hosni Mubarak’s “day of departure” set to collide with Mubarak’s gradually increasing use of force to try to back them down.

It didn’t turn out that way. The protesters managed to once again rally hundreds of thousands of people in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, and untold thousands more in cities across Egypt, but in the end the day passed with no confrontation between the protesters and the government. And Mubarak hasn’t gone anywhere. Moreover, it seems increasingly unlikely that he actually will go, at least until elections are held in September.

How did things come to this?

Mubarak’s Gambit

For the student of power politics, one of the fascinating things to watch as this crisis has unfolded has been how masterfully Mubarak has played what initially appeared to be a pretty weak hand. He didn’t start strong; he ignored the protests for far too long after they began on January 25, and on January 28, the “day of rage,” he inexplicably waited all day before making a statement, leading to widespread speculation that he had fled the country or simply died. (The man’s 82 years old, after all; it wasn’t hard to imagine him simply keeling over from shock.)

When he did speak on the 28th, though, he managed to take a storyline that seemed already written and turn it upside down. Up to that point, he seemed stuck in a no-win scenario; the only options that appeared open to him were either to give the protesters want they wanted and step down, or drive them from the streets with force and risk igniting a revolt by the army and becoming an international pariah.

Mubarak’s speech on the 28th broke him out of the lose-lose scenario by rejecting both choices and presenting instead a third option. He had heard the public’s anger, he said, and he would act to address it, but only by turning out his cabinet, not by stepping down himself; and while he did not approve of the protests, he would not crack down on them and make the protesters into martyrs of democracy, either.

By doing so, he took the lose-lose situation that had previously been his to wrestle with and flipped it onto the protesters. Mubarak’s January 28th speech established that he did not see peaceful protests, in and of themselves, as enough to drive him from office. As long as the army supported him, or at least stayed neutral, he seems to have calculated that he could ride them out; he would respond to such protests with some incremental reform proposals, but that’s it.

Mubarak, in short, told them that their protests alone would not be enough to send him packing — and then dared them to do something that would.

This turned out to be a remarkably potent strategy. We’re now more than a week down the line from that speech, and it’s clear that the protesters are still trying to figure out how to respond to it effectively. If peaceful protest is not enough, does that mean that Mubarak can only be unseated with violence? If so, how do liberal-minded protesters go down that road without risking things spinning sickeningly out of control?

These are questions that nobody in the democracy movement appears to have answers to. Which was probably why Mubarak wanted to throw them on the horns of this dilemma in the first place. He was gambling that they wouldn’t call his bluff, and so far it’s a gamble that seems to be working.

The Stakes

Currently, the Obama administration appears to be trying to split the difference between the protesters’ demands and Mubarak’s “concessions” by accepting the concessions and urging the protesters to accept them as good enough. But to ask that of them now defies the logic of living in a police state.

The proposal is that the protesters take the concessions, go home, and then come out again at election time in September and support pro-democracy candidates. The problem is that if they leave the square now and Mubarak is still in office, it’s unlikely that many of them will still be alive and on the streets in September.

The organizers of the protests are safe from Mubarak’s wrath today because the glare of the world media is upon them. If they were to suddenly “disappear,” they would instantly be missed. Take, for instance, the case of Google executive and protest organizer Wael Ghonim, who was seized by Mubarak’s secret police on January 28 and released today. Ghonim’s absence was immediately noted, because while the protests go on the protesters are all in contact with each other.

Imagine, though, if the protesters accepted Mubarak’s half loaf, packed up their signs and went home. Mubarak — or, more accurately, Mubarak’s feared secret police, the Mukhabarat — would then have eight long months in which to pick each of them up as they go about their daily lives, far from the prying lens of al-Jazeera. Locally they might be missed, but what are the odds that the world media would notice? Would anyone connect the dots of a vanished student here, a mysterious car accident there, and realize that Mubarak was quietly spending his eight month reprieve taking his revenge? And even if they did, would it be a front page story?

Of course not.

That’s the dilemma the protesters are up against. At this point, they are, effectively, all in. Either Mubarak goes down loudly, or they go down silently, picked off in the shadows, one by one.

Emerson’s Law

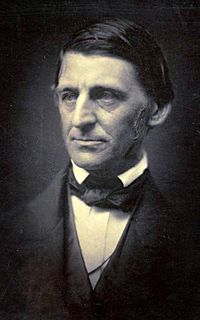

In his 1884 biography of his friend, Transcendentalist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, the celebrated physician and writer Oliver Wendell Holmes recounts a nugget of practical wisdom from the Sage of Concord:

In his 1884 biography of his friend, Transcendentalist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, the celebrated physician and writer Oliver Wendell Holmes recounts a nugget of practical wisdom from the Sage of Concord:

A young friend of mine in his college days wrote an essay on Plato. When he mentioned his subject to Mr. Emerson, he got the caution, long remembered, “When you strike at a King, you must kill him.”

This is advice that has pertinence far beyond Plato. For those who would make a revolution, the worst-case scenario is to strike at the established order and merely wound it; a wounded dictator is much like a wounded beast, lashing out furiously with tooth and claw, mauling both those who struck it and those innocent civilians who happen merely to be in the way.

This does not mean that you must kill a dictator to kill the dictatorship — the web of institutions that make up a government is not necessarily the same as the man inside it. (In Egypt, for example, Mubarak could likely be unseated without violence if a way could be found to separate him from the army, or to force the army to choose between standing with Mubarak and standing with the people, rather than straddling the fence.)

However, it does mean that if you wish to strike at a dictatorship, you must understand that the only blow you will have the luxury of striking unopposed will be your first. Should that miss its mark, you will urgently need to have an answer to a simple question: what do we do now?

This is the question the Egyptian revolution is wrestling with today. Only time will tell if they will find an answer before it is too late.

UPDATE (Feb 10): Mubarak blinks? Several news outlets are reporting that he may step down…

UPDATE (Feb 11): Nope, didn’t happen. I was watching the live Al-Jazeera feed from Tahrir Square when Mubarak made his non-announcement announcement, and the anger and frustration in the crowd there was palpable.