The act of generosity that changed the world

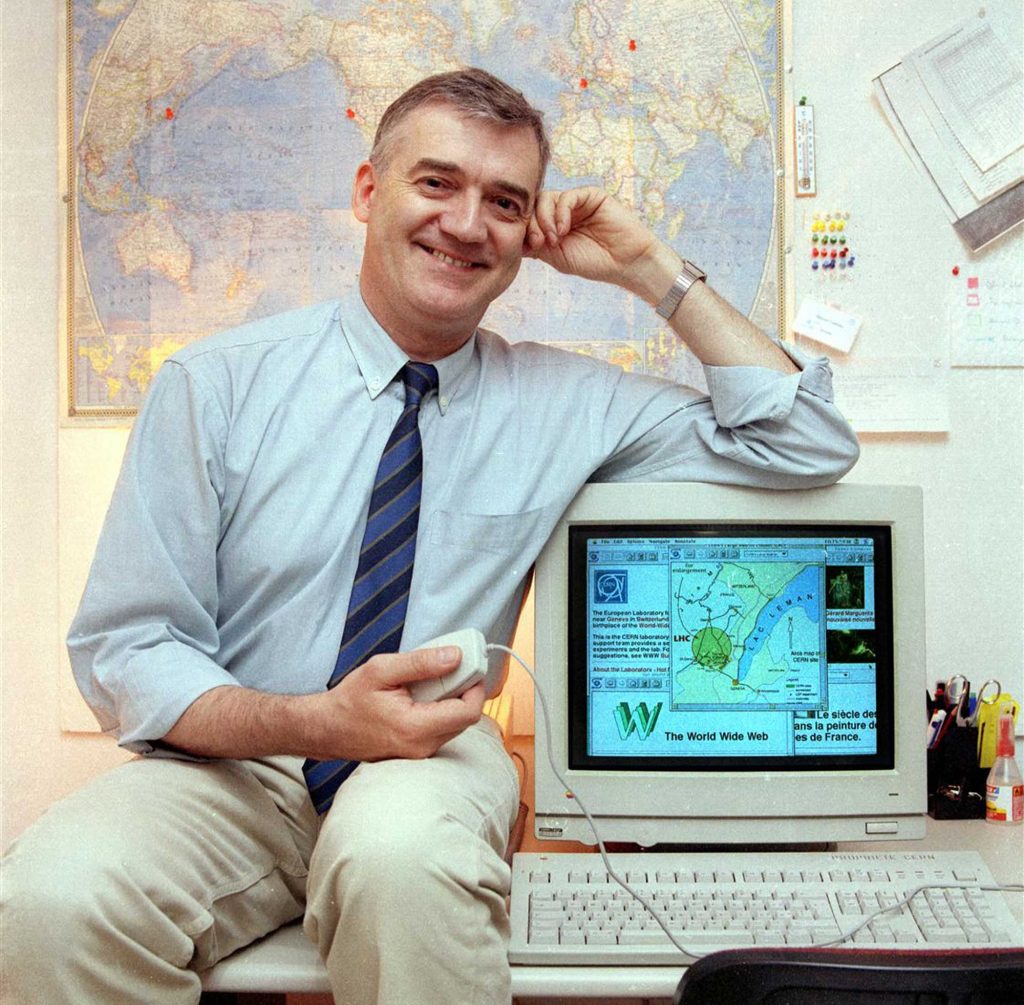

Robert Cailliau, June 1995

April 30th was the 20-year anniversary of the decision by CERN, the institute where Tim Berners-Lee worked when he invented the World Wide Web, to place the original Web technologies into the public domain. The original legal statement that did so is here.

It is difficult to overstate the significance of that decision. Putting the WWW technologies into the public domain meant that anyone could pick them up and hack on them, without needing to get permission from CERN or pay a licensing fee. This led to lots of people around the world doing just that, which gave the Web a huge surge of early momentum that propelled it past other hypertext systems and started it on the road to becoming the universal gateway to information it has become.

The decision to release WWW into the public domain came from Berners-Lee and his first collaborator on the project at CERN, Robert Cailliau (pictured, in June 1995). Cailliau then spent months (Cailliau’s account says six, Berners-Lee’s says eighteen) lobbying CERN’s bureaucracy to bring them around to the same conclusion.

It was never a given that CERN would go the route it did with WWW. They could have chosen to patent it, in hopes of having more direct control over its future and reaping licensing fees from those who would use it. In fact, that was the route that was taken by the fledgling WWW’s biggest contemporary competitor.

Gopher was an information system developed by a team at the University of Minnesota led by Mark McCahill. Like WWW, it was a hypertext system, and also like WWW it was built on the Internet rather than on a proprietary corporate network. Gopher sites were connected together in “Gopherspace” via hypertext links, so you could surf from one to another in much the same way Web users do. Also like WWW, it found an early niche in academia, one of the few sectors where connectivity to the Internet was widespread in the early ’90s.

So Gopher was a lot like WWW. But in one crucial way, it was different — the University of Minnesota didn’t set it free. They chose instead to charge a licensing fee to anyone who wanted to use their version of the Gopher software. This decision was damaging to Gopher in two ways: first, it turned off lots of potential new users from just picking up the existing Gopher software and doing cool stuff with it; and second, it dampened the enthusiasm of developers outside the U of M for writing their own Gopher software, out of fear that the university might claim their ownership of the Gopher concept gave them an ownership stake in their product too. Using the WWW meant not having to deal with any of these worries, so people fell away from Gopher and went to the WWW, and the rest is history.

And that history changed a lot of peoples’ lives, including mine. I first encountered the Web during my freshman year in college, back in 1994. It was one of those moments you remember for the rest of your life; I’d been tinkering with computers since I was a little kid, and I came out of high school convinced that widespread ownership of computers was going to change society in some profound way, but I had no idea what that way would be. Then I saw the Web, and all the exciting things that were bubbling up around it thanks to CERN’s decision to free it, and was struck with the thought that this is it — this is the lever that is going to move the world.

The next thought I had was I need to find a way to be a part of this, and the rest of my life since that day has more or less flowed directly out of that thought.

(It was such a strong feeling that I actually spent the next couple of weeks after that first experience debating whether I should drop out of school and go to Silicon Valley to try and get in on it somehow. In retrospect, I’m glad I didn’t — I didn’t have any skill at that point in the kinds of programming languages needed to get a foot in the door then, like C/C++, so I probably would have failed spectacularly. The adventurous side of me still wonders occasionally if I might have gotten lucky had I tried it, though.)

So while I haven’t been doing this for twenty years quite yet, it’s getting pretty close to that. Had CERN locked up the Web behind patents or licensing fees, it’s unlikely the Web would ever have become as lively and interesting as the one I encountered in the university computer lab that day. (I actually used Gopher a bit around the same time, and it struck me as interesting but less fundamentally important; in retrospect, that was probably because you could just see more people doing more interesting things with the Web than you could with Gopher, thanks to Gopher’s more restrictive licensing.) And if that had been the case — if the Web had struck me as an interesting toy, but nothing more — I honestly can’t tell you what I would be doing today. The direction of my life was altered too fundamentally by Berners-Lee and Caillau’s decision for me to imagine now what other way it would have gone.

And there are lots of others who could tell the same story, some of whom have made billions. It’s easy to add up all the money people have made off their invention and say “wow, if Berners-Lee and Cailliau had chosen to lock WWW up they could have made all that money themselves.” But of course, the foundation for all those successes was the fact that the Web was an open platform. Building something like the Web we know today, in other words, required as its first, catalytic step a fundamental act of generosity. Without the galvanic effect of that step, none of the online services we know today, large or small, would have crawled out of the primordial ooze.

So this seems like as good a moment as any to say thank you to Berners-Lee, Cailliau and CERN. Their generosity changed the direction of history — but (more importantly to me!) it changed my life, too. It made my life, at least that part of it I have lived to date. And that’s something worth being thankful for.