Trump and Sanders: winning 2016 by a thousand OODA loops

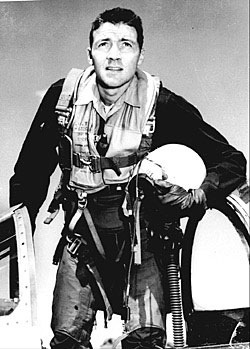

I’ve written before in this space about my admiration for the thinking of John Boyd, the fighter pilot whose ideas on strategy revolutionized the American way of making war. So I wanted to take a moment to point out how brilliantly the 2016 Presidential campaign is illustrating one of his key insights: the central role in deciding victory or defeat of the decision-making model he called “the OODA loop.”

I’ve written before in this space about my admiration for the thinking of John Boyd, the fighter pilot whose ideas on strategy revolutionized the American way of making war. So I wanted to take a moment to point out how brilliantly the 2016 Presidential campaign is illustrating one of his key insights: the central role in deciding victory or defeat of the decision-making model he called “the OODA loop.”

How we make decisions: the OODA loop

One of the subjects Boyd was intrigued by was the question of by what processes people turn the ambiguity they swim in every day into decisions that lead to concrete action. We live in a world of unimaginable complexity, with so many possible variables to consider that if we actually tried to consider them all before acting we’d be frozen in “analysis paralysis” forever. But we’re not frozen; we are constantly acting, in big ways and small. So how does that happen? How do we decide to act, and why do we make the decisions we do?

The name he gave to the model he eventually developed to explain this, the OODA loop, derives from the four stages he believed the human mind goes through in the process of moving from uncertainty to action. These are:

- Observe: Gather facts about the situation

- Orient: Fit the facts together with pre-existing mental models to develop a narrative of what is happening that makes sense

- Decide: Choose a course of action that seems appropriate based on that narrative

- Act: Translate that decision into some real-world activity that we believe will bring the situation more closely in line with our goals and desires

When the action is complete, Boyd argued, we cycle back to the beginning of the process, observing the effects of our actions in order to inform our next decision. (Which is what puts the “loop” in the OODA loop.)

Boyd’s insight went beyond just describing this model, though; he also articulated how central it is to any concept of strategy. In any contest, he said, the adversaries are constantly cycling through their own OODA loops, choosing ways to strike at their opponents and then evaluating how effective those strikes were. In such a process, therefore, the advantage will always go to the contestant who traverses their OODA loop more quickly than the other. As long as you can do so without sacrificing accuracy, cycling through your OODA loop more quickly means having more opportunities for action — more bites at the proverbial apple. Conversely, the slower your trip around the loop, the fewer actions you will be able to squeeze into a given period of time, leaving you vulnerable to a more nimble adversary.

In other words, if you can get yourself in a position where you are consistently lapping your opponent as you make your respective trips through the OODA loop, you are very likely going to defeat them. (In Boydian terms, reaching this position vis-á-vis an adversary is called “getting inside their OODA loop.”)

Get to the point already

So what does all this have to do with Presidential politics in the year 2016?

I would submit that it’s a big part of the reason that Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, two candidates who were widely dismissed as novelty acts when the campaign began, are currently doing so well. They have managed to get inside their opponents’ OODA loops.

This is not because either of them has figured out some particularly novel way of running a presidential campaign. They’re not making their trips around the OODA loop faster. What they are doing though — simply by existing! — is making their opponents’ trips around their OODA loops slower.

The weakest link in anyone’s OODA loop is that second “O” — “orient.” It’s the stage of the process where you take the raw data that is the evidence of your senses and turn it into a narrative about what is happening around you and why. But there’s no way to do that just with the data you’ve just now observed; you need to have a mental model of how the world works already in place to provide scaffolding to hang those data upon.

Luckily, every sentient person develops such a mental model as they live their lives, so that’s rarely a problem. But the thing about those mental models is that, once they’re formed, we tend not to update them very often — even as the facts of the world are changing all around us. Which means that, in times of social change, it’s fantastically easy for those models to slowly drift out of alignment with reality.

And when that happens — when your mental model of how the world works stops corresponding in any meaningful way to the way the world actually does work now — “orientation” in the OODA sense starts becoming more and more difficult the farther from reality your model drifts. You’re suddenly having to take facts that just don’t fit into your mental model, and find a way to jam them in there somehow regardless. That takes work, which takes time; and the longer you spend trying to orient yourself, the slower your trip around the OODA loop becomes.

2016: Death by a thousand loops

This is what Trump’s and Sanders’ opponents are struggling to deal with right now. In their mental models, Trump and Sanders are candidates who should not be viable in a national political contest. The rules of American politics as they understand them don’t admit any possibility for a reality TV clown or an unreconstructed socialist to find success. It simply should not happen. But every day sends them fresh evidence that it actually is happening — evidence that they, and their staff, have to find a way to integrate and react to. So they’re constantly playing catch-up; constantly getting caught on the back foot. And worse, the more the evidence that their model is wrong piles up, the slower the process of orientation becomes; facts that shouldn’t be true but are accumulate on their mental model like barnacles on the hull of a ship, slowing them further with each new one that fastens on.

I don’t think this is due to any individual peculiarity of their opponents. Rather, it’s due to a shared failure to update their mental models after what is probably the most consequential event in recent history: the massive financial meltdown of 2008. They failed to realize how deeply that event discredited the old politics, which opened opportunities for new types of candidates, untainted by the old politics, to find purchase. They thought it was just another bump in the road that could be massaged by tweaking their messaging, adjusting their “optics,” instead of a fundamental challenge to the order of things.

Not only did they think that in 2008, they still think that. Which is why they can’t seem to find a way to react to Trump and Sanders, who, for all their many differences, are the only two candidates in the race who understand that things have changed in deep and fundamental ways. As long as their competitors fail to integrate this reality into their mental models, Trump and Sanders will remain comfortably inside their OODA loops.