The End of New Orleans: What Leadership Isn’t

Posted on September 9, 2005

One of the most often offered defenses for the President in the Katrina who’s-to-blame sweepstakes has been that it’s not his job to respond to natural disasters — that this role belongs to state and local officials instead. Therefore, the argument goes, the real blame belongs to the governor and the mayor, not the President.

Even before the water stopped flowing into the soup bowl, this pathetic defense was being proffered by Bush’s most stalwart defenders. For the purposes of this essay let us refer to these dogged souls as the proud citizens of Wingnutistan.

To address this defense, let’s play a little game of “what if”.

First we must lay down the ground rules of the exercise. The central one is that — in order to plumb the true accuracy of the argument — we will temporarily suspend disbelief and grant the citizens of Wingnutistan their every fevered postulation. We will accept the portrait of Mayor Nagin as a clueless bumbler fleeing the scene of the disaster. We will accept the characterization of Governor Blanco as a weak reed prone to uncontrollable fits of emotion (she is, after all, a — gasp! — woman). We will accept that President Bush, down on his ranch in Crawford, was pleading in mounting frustration with the feckless Blanco and the clueless Nagin to do something, dammit! in between his photo ops with the cake and the gee-tar. We will even accept that not even a declaration of a state of emergency, issued by Governor Blanco and signed by the President, provides enough authority for the Federal government to act decisively. And — finally — we will accept that, when he realized that Blanco and Nagin weren’t going to act, that he himself was powerless to do so due to Constitutional Impediments of Unusual Size.

In other words, we shall swallow in toto the way the story was being reported in Wingnutistan, no matter how implausible some of its ingredients are.

And now, our thought exercise. Imagine the President, sitting there on his ranch, seeing the disaster unfold in New Orleans and being unable to stop it. Since he was completely on top of the situation, he would have been notified immediately when the levees failed on Monday morning.

Now, imagine for a moment if that night — Monday night, as water poured into the city and the rescue teams tried desperately to plug the breach — President Bush had requested time from the television networks and addressed the nation with the following:

My fellow Americans,

Like you, I have been watching the situation developing along our nation’s Gulf Coast with great concern. A natural disaster of a scope unprecedented in our lifetimes appears to be underway. I want to share with you what we, as a nation, are going to do to respond.

The first line of protection we have in crises like this are the brave men and women who work as first responders at the local and state levels. Right now, in the city of New Orleans, hundreds of these dedicated professionals are at work doing everything they can to save lives. The scale of the disaster, however, threatens to overwhelm them; and unless they receive assistance, American lives will certainly be lost.

Therefore, after much consideration, I have decided to step in and deploy the resources of the Federal government to ensure as many lives as possible are saved.

Effective as of now, under my authority as the Commander in Chief of the United States Armed Forces, and in response to the declaration of a state of emergency by the Governor of Louisiana, I declare the city of New Orleans, Louisiana and its surrounding parishes to be under martial law. Troops of the United States Army are being deployed as I speak to restore order to the city and allow relief supplies to be provided efficiently. Civilian authorities at the state and local level will be incorporated into the military chain of command.

“But!” I can hear you thinking. “But what about those Constitutional Impediments of Unusual Size?” The President continues:

Some of you may be wondering if I have the legal authority to take such a step. Others of you may fear that to do so would set a dangerous precedent, even if the law grants me the authority.

These are valid and important questions. The continuing freedom of any republican government is ensured only when the powers of the executive office are kept within bounds. The alternative is tyranny.

The relevant law in this case is the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878. This Act forbids the use of military forces for law enforcement within the United States unless approved by Congress.

I could submit this proposal to Congress and wait for their approval. However, even if they reconvene and approve it as quickly as possible, another day will have gone by and hundreds more citizens will have died. I cannot in good conscience allow that to happen.

Therefore, I have spoken with the majority and minority leaders of both houses of Congress and informed them of my decision to declare martial law over the affected area. I have also requested them to empanel a joint committee to oversee this action, and to investigate, once the crisis is resolved, whether or not my action is in accordance with the Posse Comitatus Act, the Homeland Security Act of 2002, and my oath of office.

I am confident that the committee will find that this step was not taken lightly, and that any other course would have led to greater loss of life. I have also requested them to review the laws governing our disaster response system for consistency, so that my successors in this office need not resort to measures such as this to save American lives in times of crisis.

If, however, the committee should find that I arbitrarily and without sufficient justification acted outside my Constitutional authority, I shall accept their decision and step down from the office of President of the United States. In that circumstance, the Vice President will serve the remainder of my term in office.

My fellow Americans, the time to argue questions of jurisdiction is not when our neighbors and loved ones are drowning. I act now to prevent that, and the responsibility for the action is mine and mine alone. Let us turn now together to the work of rescuing the people of the Gulf Coast from the terrible circumstances that have befallen them.

The lesson of our thought exercise is that, when you are the President — the Chief Executive — you can always do something. Even when everything breaks against you; when you are tied down by a million threads; even when the letter of the law conspires to undermine its spirit, you can still act. You can still make the difference…

…if you’re willing to take the responsibility for your actions.

Taking responsibility, you see, is what leaders do. They use their own prestige to break the Gordian knots that tangle up every human endeavor. They give others permission to act by saying to them “don’t worry — if it doesn’t work out, it’s my fault, not yours”, allowing them to sidestep the nagging fear that keeps people so often from stepping up.

And that is what is so craven about the Wingnutistani defense, and indeed about Bush’s handling of Katrina in general. It’s that even if you grant the wingnuts everything — even if you spread the blame to everyone else but the President — things could still have been different had Bush been willing to take charge, to take responsibility. But he did not, or could not, for reasons known only to him.

Did Nagin and Blanco screw up? Probably; I’m sure there will be more than enough blame to go around when all is said and done. However, in the final analysis, when a natural disaster of this size hits, it’s just silly for the Chief Executive of the nation (or his lackeys) to argue that dealing with it is not in his job description. Even if it isn’t, he should know that at his level excuses are not acceptable: nobody cares if the dog ate his homework and he is evaluated, in the end, on performance in very simple terms. Did he do everything he could to protect the general welfare, or didn’t he? Did he do everything he could to provide for the common defense, or didn’t he?

Does he take his office and its responsibilities seriously? Or doesn’t he?

These are the metrics that history uses to cast its judgements.

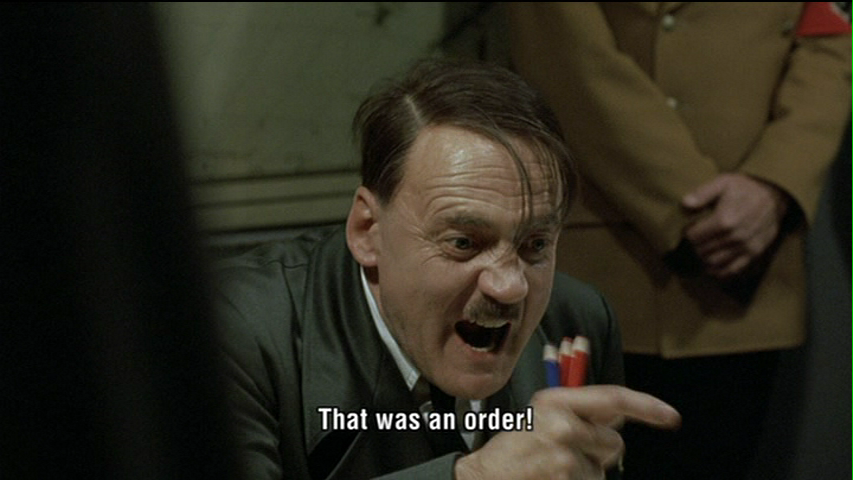

Can you imagine George W. Bush making a statement like the one above? Can you imagine him stepping out on a limb to save the life of a stranger, if that’s what it takes to save that life?

If not, ask yourself whether that feels like “leadership” to you. And if it doesn’t, ask yourself if maybe the next time you go to the voting booth you shouldn’t demand more for your vote.

UPDATE: Tony Pierce is making the same point, more eloquently than I, as usual:

let me tell you a few things about being a leader.

a leader saves peoples lives and worries about his job later.

a leader cuts his vacation short when he sees that people of his nation are drowning and help is not in the way.

a leader is that help on the way…

a leader says, just like he said at gitmo, what law, im going to fucking save the world, i dare you to impeach me for saving 10,000 people you fucking fucks, impeach me for saving lives and watch your party disappear.

a leader does what the group is either too afraid to do or too stuck in excuses to do. its why they say leaders rise to the top. its why they say leaders are born not made. its why they say follow the leader. its why i say mr bush is not a leader.