How to crusade like a king in Crusader Kings II

Posted on July 24, 2012

I’ve written in this space before about how impressed I’ve been with the latest strategy game from Paradox Interactive, Crusader Kings II, and its first expansion, Sword of Islam. Those posts led to a discussion on Facebook asking me to expand on them a bit, by taking them down to a more concrete level: strategies for how to play them and win. So, here’s a post that will do just that.

I should preface this with a couple of notes. First, the tips below all assume you’re playing a Christian king; Sword of Islam allows you to play as a Muslim, and introduces some new mechanics for Muslim characters, but that’s a subject for another post. Next, I’m hardly one of the world’s foremost experts on CK2. There’s lots of people who have delved far more deeply into the game’s mechanics than I ever have, and you can find them all in one place: the indispensable Paradox forums. The community that posts there is thoughtful, respectful, and really, really smart. If you’re interested in talking CK2, you should definitely create an account and join the discussion there. There’s also a Wiki where players are gathering information to make a comprehensive reference on how CK2 works. Finally, if you want more of a tutorial walkthrough than a collection of general tips, there’s an excellent thread at Something Awful that walks you through the game in great detail.

That being said, on to the tips…

Start small. New players have a natural tendency to want to start the game playing one of the larger empires — France, say, or Byzantium. The assumption they’re making is that it’s easier to play a big, powerful kingdom than it is to play a small, weak one. But in CK2, the opposite is true. CK2 is a game about relationships, and when you’re running a huge empire, you have a lot of relationships to manage all at once, which can be overwhelming. Choosing a smaller nation lets you learn the ropes by dealing with a much smaller cast of characters.

Start small. New players have a natural tendency to want to start the game playing one of the larger empires — France, say, or Byzantium. The assumption they’re making is that it’s easier to play a big, powerful kingdom than it is to play a small, weak one. But in CK2, the opposite is true. CK2 is a game about relationships, and when you’re running a huge empire, you have a lot of relationships to manage all at once, which can be overwhelming. Choosing a smaller nation lets you learn the ropes by dealing with a much smaller cast of characters.

There’s lots of opinions about which kingdom is the best for new players to start with, but the consensus in the forums is that (if you’re starting the game at its earliest start date, 1066) any of the provinces of Ireland are ideal “starter kingdoms.”

There are several reasons for this. Most of them only have a couple of provinces you need to manage, which reduces the number of variables you have to juggle to the absolute minimum. In 1066, Ireland is divided pretty equally among several small kingdoms, so you don’t have a big, powerful neighbor threatening you right away; all your neighbors are just as weak as you are. There are powerful nations in the region, like the Normans; but they’re all separated from you by ocean, which makes it harder for them to invade you and thus defers the day when you’ll have to deal with them. And all the Irish provinces have a natural goal — unification of the island into a single Kingdom of Ireland — that makes for an ideal “tutorial quest”; once you’ve learned the game enough to bring the rest of Ireland under your control, you’ll have learned all the essential skills you need to run a kingdom of any size.

Think like a Godfather, not like a President. If you’ve played strategy games before, or really if you grew up anytime after the year 1648, it’s natural to think of your kingdom in terms of a nation — a cohesive political entity that has a unique identity transcending whomever happens to be ruling it at the moment.

To be successful in CK2, you need to rid yourself of that notion, because it didn’t exist in the medieval world. Back then, the concept of the state was inextricably mixed up with the concept of the ruler; the state, and everything in it, were the personal property of the king and his family. Or at least they were as long as the king could keep another king from coming along and taking it from him. It wasn’t a nation as we understand the word today; it was the king’s “turf.”

Take the example of the Irish provinces, mentioned above. Let’s say you choose to play as the duchy of Connacht. That might sound like you’re choosing a nation to play as. But really, you’re choosing a family — specifically the Ua Conchobair, the family from which sprang the historic Kings of Connacht during that period.

The reason this is important to understand is that your job in CK2, if you go down this road, is not to work for the greater glory of Connacht. Let me say that again: as Duke of Connacht, your job is not to protect and expand the power of Connacht. Your job is to protect and expand the power of the Ua Conchobair family. Connacht is merely the raw material you use to make that happen.

This means like the road to success isn’t to think of yourself as “leader of Connacht.” It’s to think of yourself as the Godfather of the Ua Conchobair family, in the same way that Michael Corleone was the Godfather of the Corleone family in the Godfather movies.

This particular example, in fact, is instructive. If you think back to the first Godfather movie, you’ll remember that it’s established that the “turf” of the Corleone family is in New York City, and has been ever since the original Godfather, Vito Corleone, carved it out after arriving from Sicily at the beginning of the 20th century. At the end, though, we see Michael pick up the entire Corleone empire and move it to Nevada, because he judges (correctly!) that the future of organized crime is going to be found there. Lieutenants who want to stay in New York for sentimental reasons are ruthlessly cut loose from the family. Crime figures in Nevada who stand between Corleone and the “turf” he wants there are gunned down.

This is how you have to think to be successful in CK2. Playing as Connacht, for instance, it’s possible to win glory for your family by taking on your immediate neighbors, wresting their kingdoms from them, and taking them as your own. But it’s equally possible to win glory for your family by marrying your children strategically into the dynasties of a distant, powerful kingdom, yielding children of your own blood who grow to rule it, or by taking the cross and carving out a Crusader kingdom in the Middle East, planting crowns of sandy kingdoms upon the heads of your children. It’s quite possible for the family Ua Conchobair to grow to great power, in other words, without Connacht growing any further on the island of Ireland. It’s even possible for the family to prosper without any holdings on the Irish isle at all.

Play dynastically. This leads to a related point, which is that if playing as a family rather than a nation is the way to go, ensuring the continuance of your family line is of the utmost importance.

What this means, at the most basic level, is heirs; specifically, male heirs. You must have male heirs for the family to continue. There are lots of ways to lose a game of CK2,but the easiest is to get so wrapped up in other things that your character never gets around to fathering any male children. Whoops! Game over.

Image from Something Awful’s CK2 tutorial thread (click image to read)

And it’s not enough to just produce male heirs. You have to produce decent male heirs — “throne-worthy” male heirs, in the terminology of the time. Here is where understanding of character statistics and traits comes in. Statistics are the numeric scores that are attached to a character — things like “Diplomacy,” “Intrigue,” “Martial,” etc. Traits are the character attributes displayed as icons — things like “Brave,” or “Drunkard,” or “Hunchback.” Together these define a character.

How they affect what the character himself does is pretty obvious; a character with a high Martial score and the “Brave” trait will do well on the battlefield, for example. What’s less obvious is that a character’s statistics and traits also affect how other characters perceive and react to that character. So if your male heir has that “Brave” trait mentioned above, other “Brave” characters will admire his courage, raising their opinion of him; but characters with the “Craven” trait, importantly, will envy his courage, lowering their opinion of him.

This means that whether or not your heir is accepted by the rest of your court will depend in part on his raw stats, and in part on who exactly the other people in the court are. Some traits are seen as more “kingly” than others — an heir who is Charitable will generally have an easier time picking up his father’s crown than one who is Greedy. (In CK2’s taxonomy of traits, these are known as virtues — trait icons with a green background and a number on them. The opposite of virtues are sins — numbered trait icons with a red background.) But a Charitable heir in a court full of Greedy vassals and advisors may find that his virtue alone is not enough to ensure his succession.

The less “throne-worthy” your heir is judged by your other vassals (including his siblings!) to be, the more likely it is that upon your character’s death they will launch bids to wrest the crown from your heir’s hands into their own. These bids can lead to long, destructive civil wars that break up a mighty empire, so it’s critical that you do everything you can to ensure that when your character dies, a strong, capable heir is waiting for you to play as next.

Breeding is important. There’s three ways you can affect the likelihood of producing a throne-worthy heir.

The first: marry the right person. Parents can pass some of their traits on to their children, so if you marry your character to a paranoid, lunatic hunchback, you should not be surprised when your kids turn out to be less than ideal. Similarly, a child who has the “Inbred” trait has huge negative modifiers applied to their stats, so you don’t want to marry within your own family if you can avoid it.

The second: have lots of kids. Having too many kids can pose a problem, since kids (especially male kids) tend to expect Dad to give them a province to run when they reach adulthood at age 16, so having more kids than provinces can cause disputes within the family. But those problems are usually easier to deal with than the ones that come from not having a decent male heir.

The third: educate your kids well. When a child is born in CK2, his or her initial stats and traits come from the stats and traits of its parents. But as he/she grows up, his/her “personality” is shaped by the people you surround them with. This gets more pronounced at age 6, which is the age when a child can start their education. “Education” in the world of CK2 doesn’t mean sending them to school, though — it means assigning them a guardian, another character from your court, to whom they become a sort of apprentice. The traits of a child’s guardian can be picked up by the child, so for your oldest kids, anyway, it’s worth taking a little time to find someone with good, throne-worthy traits to educate them; there’s no guarantees the kid will learn from their example, but it can’t hurt to try. (Note that you can choose to make your own character your child’s guardian if you wish; this gives you the chance to mold the child’s character directly by choosing how to react to events in the child’s life, but if your character has negative traits, it’s possible you can pass them on to the child as well.)

Note that guardians don’t just have the opportunity to pass along their traits to the children they educate; they also have the opportunity to pass along their culture as well. That means that if you’re an Irish king, and you give your oldest son to a character from France to educate, there’s an outside chance that when the kid’s education ends he’ll come away acting a lot more like a Frenchman than an Irishman. This kind of cultural difference is a huge turn-off for vassals — no self-respecting Irishman in 1100 would want to live under a Frenchified king! — which can make passing the crown to them quite difficult, as vassals revolt left and right to install a “true Irish king” instead of your weird son. Similarly, a guardian can pass along their religion as well, and heretics have a hard time rising to the throne of a Christian kingdom; so if there’s a guardian who looks great except for the minor problem that they belong to an heretical church, think hard before handing your kid over to them.

Know the law. The last piece of keeping your dynasty alive is making sure that the laws of your kingdom make it easy to do so. Different kingdoms in CK2 have different laws governing which children can succeed a king. You can change these laws to better suit you, but you can only do so once in each character’s lifetime, and only after that character has held the throne for at least ten years; and changing it can have major negative impacts among those characters who are affected negatively by the change (like children who used to be in the line of succession, but now are not). So it’s worth thinking carefully about which approach you want to take to succession over the long term.

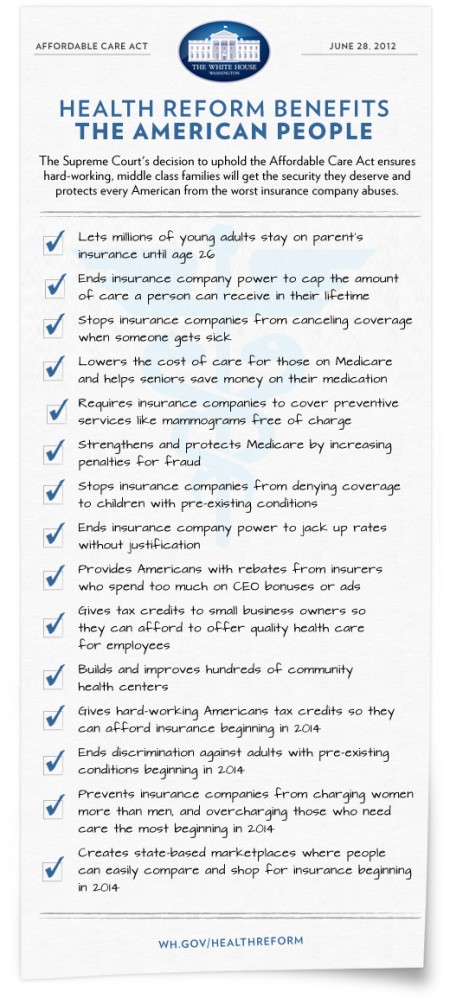

The relevant laws fall into two basic categories: gender laws and succession laws. Gender laws determine how (if at all) women fit into the line of succession; succession laws determine how the line of succession is organized. Not all cultures have access to all the available gender and succession laws; while it is possible to have a gender law that makes women equal to men as candidates for succession, this option is only available to a small number of cultures.

Gender laws break down as follows:

- Agnatic: Only men can succeed to the throne.

- Agnatic-Cognatic: Women can succeed to the throne, but only if no eligible male heirs are available.

- Absolute Cognatic: Women and men have equal eligibility for succession.

Succession laws break down like this:

- Seniority: The oldest member of your dynasty inherits all your holdings. (Note that this doesn’t mean your oldest child inherits; it means that the oldest dynasty member inherits, who might be your character’s younger brother, or second cousin, or even his father.)

- Gavelkind: Your holdings are divided equally among all eligible heirs.

- Primogeniture: Your oldest eligible child inherits all your holdings. If that child has died, their oldest eligible child inherits, and so on down their branch of the family tree. If they died without having any children, the process repeats with your second-oldest eligible child’s branch of the family, then the third, etc.

- Elective: You nominate a successor, who can be anyone in your court (not just your children), for each of your titles. Others can put themselves forward as candidates for succession to one or all of your titles as well. Your vassals vote on which candidate to give each title to when your character dies.

You will note that, from the player’s perspective, none of these laws are perfect; all of them carry a degree of risk to the continuation of your family line. To a lot of new players, Gavelkind succession seems like the fairest choice — why not give each of the children a slice of the pie? But when you try it you quickly discover the answer to that question: because it takes your vast kingdom and turns it into several smaller kingdoms, each with a child on the throne scheming to take over all the others. Elective seems fair to our modern, democratic sensibilities, until you realize that each of your titles gets voted on separately by the vassals who belong to that title, so if your heir is popular everywhere but one corner of your empire, it’s entirely possible for that corner to give the title to a Favorite Son of their own, peeling it off from your kingdom. And so forth.

Because of this, there’s no one “best” succession law that you should always go with; the choice depends on your play style and the makeup of your court. Personally, I tend to go with Elective — it gives you the flexibility to put a more-capable younger son up for your throne if your oldest is a drooling idiot or a heretic, and it’s usually possible to bribe or strongarm difficult vassals into voting the way you want them to. But your choice may be different.

And that’s where I’ll wrap this set of tips up for now. If you have questions about other elements of CK2, feel free to ask in the comments or on Facebook/Twitter/etc. and I’ll be happy to answer them there, or in a second post if they’re complicated.

So over at a site called “LibertarianRepublican.net” (which should give you a pretty good idea what they’re on about), Eric Dondero is pretty sure that

So over at a site called “LibertarianRepublican.net” (which should give you a pretty good idea what they’re on about), Eric Dondero is pretty sure that

Hurricane Sandy

Hurricane Sandy

Americans don’t trust their press corps to tell them the truth.

Americans don’t trust their press corps to tell them the truth.

The Interwebs have been up in arms since Michael Sippey of Twitter posted

The Interwebs have been up in arms since Michael Sippey of Twitter posted  Last year in this space I took note of the launch of a new product from Amazon.com called Cloud Player, and asked “

Last year in this space I took note of the launch of a new product from Amazon.com called Cloud Player, and asked “

I’ve been getting a kick lately out of a game called

I’ve been getting a kick lately out of a game called

Here’s something I was reminded of this morning when I checked in on Twitter and saw a stream of comments from the just-started

Here’s something I was reminded of this morning when I checked in on Twitter and saw a stream of comments from the just-started