A brief consideration of various strategic problems in “Rule the Waves”

Posted on May 9, 2016

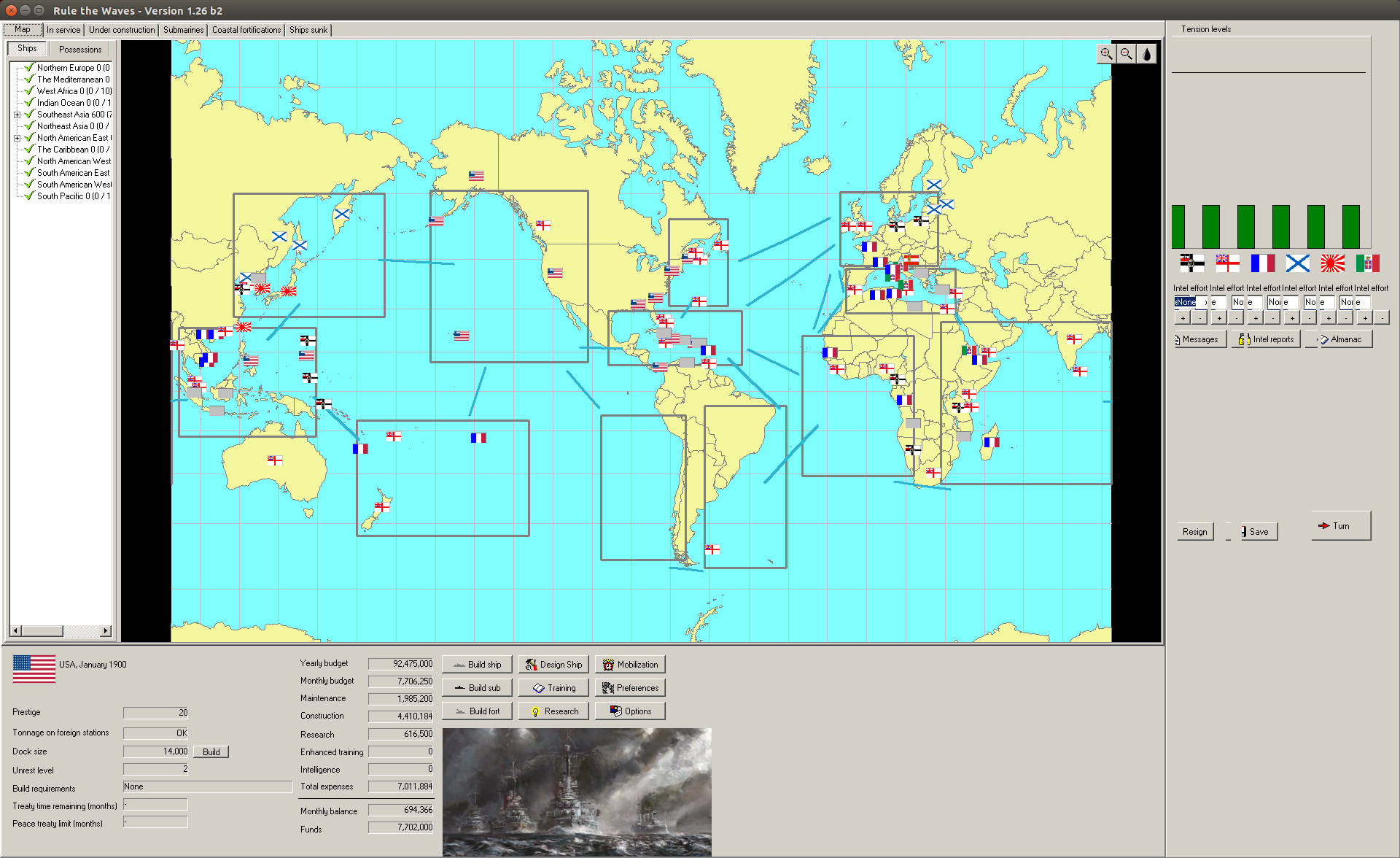

I’ve written in this space before about my love for Rule the Waves, a quirky but brilliant little game of naval strategy. It’s been a couple of months since then, and I’m still completely addicted to it; but the more I’ve played the more the game’s rough edges have come to stick out for me, and one big one is its complete unwillingness to even meet the new player half-way in terms of learning how to play it. You have to learn those lessons the hard way, by trial and error.

I’ve written in this space before about my love for Rule the Waves, a quirky but brilliant little game of naval strategy. It’s been a couple of months since then, and I’m still completely addicted to it; but the more I’ve played the more the game’s rough edges have come to stick out for me, and one big one is its complete unwillingness to even meet the new player half-way in terms of learning how to play it. You have to learn those lessons the hard way, by trial and error.

One of the most important of those lessons is learning how to play the various nations in the game, each of which has its own set of strategic challenges and unique resources to meet those challenges. So, for the benefit of newbies, I thought I’d take a moment to summarize the strategic mindset you have to take when playing each of the game’s nations to lead that power to success.

I’m going to address these in order of generally difficulty, taking the easiest nations to play as first and working my way to the hardest ones down the line.

The United States of America

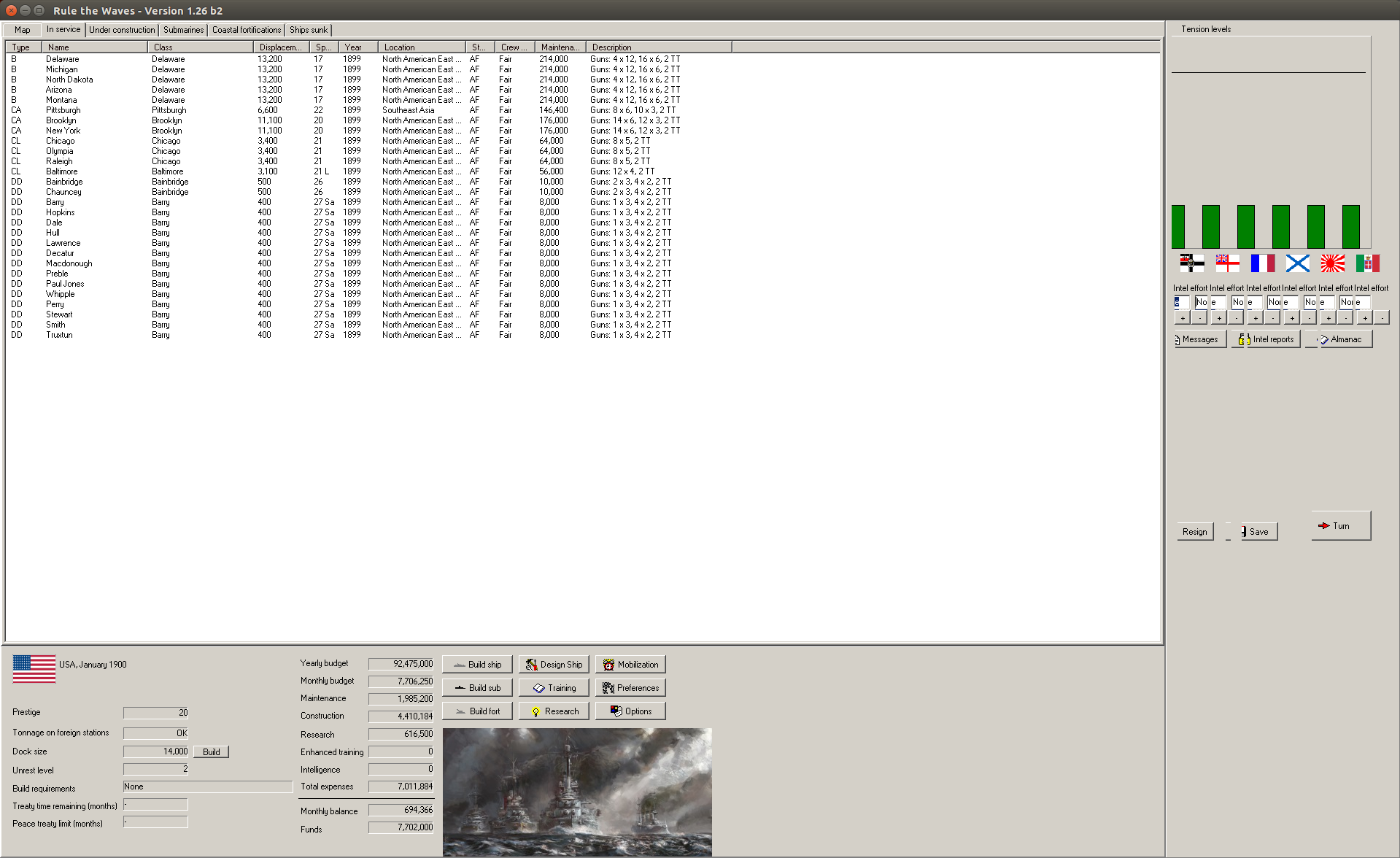

The U.S. is by far the easiest power to play as in RtW. For this reason, I generally recommend it to new players as an ideal starting point from which to learn the game’s ins and outs. It is very hard for a player playing as the U.S. to do badly. You have to work at it.

There’s a few reasons why this is. The first is geography; the home coasts of the U.S. are separated from all other powers by broad oceans, making it extremely difficult for them to operate fleets there. Only Britain, with its bases in Canada, can plausibly mount a blockade of your home ports; and Britain’s need to meet responsibilities around the world (see below) can turn even this into an opportunity for the U.S. player, since you can concentrate your fleets in North American waters and thus open the door to landings that can seize those British bases.

The U.S. has overseas responsibilities of its own, but they are minimal. Bases in Southeast Asia and the Caribbean are large enough at the start to support fleets that include battleships, but in peacetime a couple of old cruisers is sufficient to cover them. In wartime things get more complicated, since Britain, France, Germany and Japan can all operate fleets of their own in Southeast Asia while Britain and France can do so in the Caribbean, but since these stations are relatively close to your home ports (the West Coast for Southeast Asia, the East Coast for the Caribbean) you can usually reinforce your fleets there quickly. And if you can build up forces in either station, the opportunity arises to gobble up those foreign colonies and expand your own presence there.

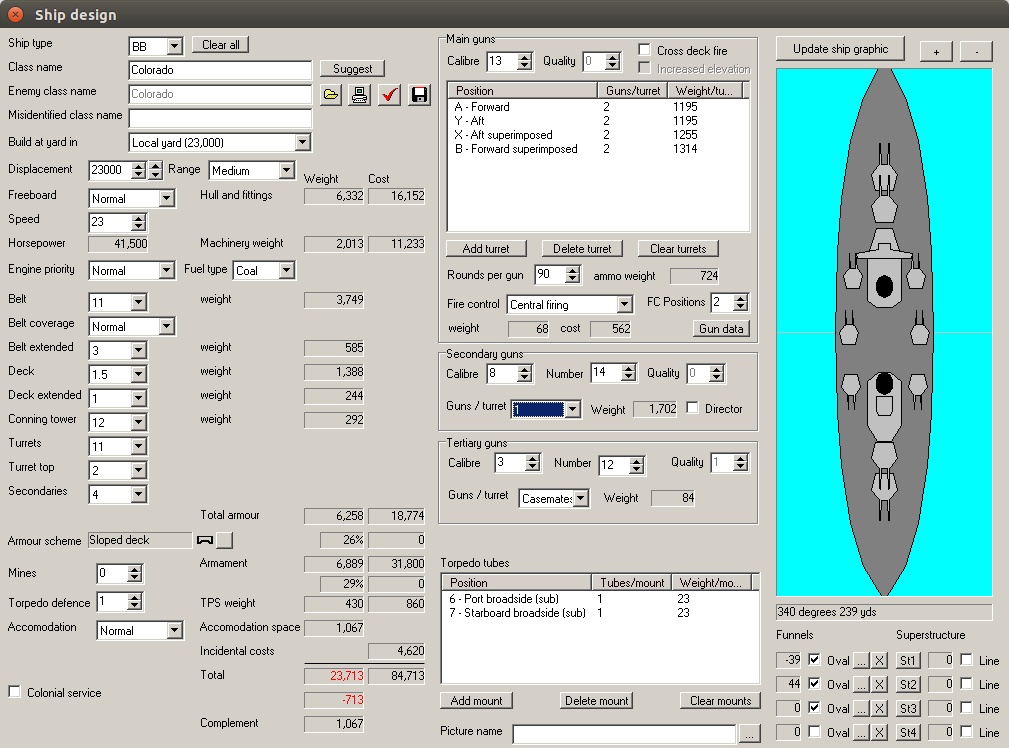

Your navy starts off with a small budget and a middling fleet, but rapid industrial development means that by mid-game you’re able to build fleets big and fast enough to directly challenge any other power. Even at the game’s start in 1900 you have ample dock space (14,000 tons) to build even large battleships without needing to rely on foreign shipyards, and if you invest modestly in dock expansion you can easily be building 40,000+-ton dreadnoughts by the 1920s.

This is not to say that everything is cream and strawberries for the U.S. player. One strategic challenge the U.S. faces is the need to divide your fleet between the East and West Coasts in order to be able to respond quickly to overseas developments; this can make concentrating your forces difficult, especially in the years before 1914 when the Panama Canal doesn’t exist. (In the absence of the canal, repositioning ships requires making the long voyage around Cape Horn, which can take four months to traverse.) Your lack of overseas possessions in places like Northern Europe, the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean can make it difficult for you to “take the fight to the enemy” in wars against powers like Britain and France. And if you do end up gobbling up those tempting foreign colonies, you can find yourself having to divide your fleet up further to meet the requirements those new possessions have for locally stationed ships to protect trade.

None of these problems are insurmountable, though, and most of them can be solved simply by relying on the nation’s increasing industrial might. In 1900, it is difficult for the U.S. to field a fleet that can truly operate globally; by 1915-1920, it’s child’s play. You have the money, you have the technology, you have the capacity to field a navy that is second to none. All that remains is for you to put those resources to work.

Great Britain

The British start the game as they started the 20th century in real life: in unquestioned control of the world’s oceans. The legacy fleet they begin with in 1900 generally outclasses all contemporaries, frequently many times over. They have the largest naval budget, the most advanced technology, and a worldwide network of overseas bases they can use to bring their fleet to bear against any opponent they wish. It’s an enviable position.

The story of most games of RtW for the British player, however, is one of managing the decline of most of those advantages. The other powers in the game are simply building too many good-quality ships too fast for Britain to be able to continue to outclass them all. And as the relative margin of strength between the Royal Navy and the rest of the world’s navies erodes, that network of overseas bases starts to look less like an advantage and more like a liability; for protecting them all means dividing your fleet up into lots of smaller units, one to cover each sea zone, and it’s impossible to make each of those fleets strong enough to be able to counter every possible local opponent. Powers like Germany, Japan and the U.S. can, by concentrating forces in their home waters, force you to reduce your fleets elsewhere to dangerous levels just to keep up with them there. It all begins to feel a bit like a game of Whack-a-Mole.

Again as in real life, the main tool available for Britain to arrest this decline is technological. You start the game with shipyards large enough to build even the largest contemporary battleships, and if you invest in research you can have the tools you need to start building dreadnoughts as early as 1903-1904. Britain is one of the few powers with such a large naval budget that it can afford to periodically completely reinvent itself, scrapping old ships before they even technically become obsolete and replacing them with new ones using the latest bleeding-edge tech. This gives you opportunities to push other powers into naval arms races they simply cannot afford to win, with aggressive construction of dreadnoughts and battlecruisers driving even well-designed foreign fleets into early obsolescence.

And if things ever do come to a shooting war, all that technology can give you serious edge. You may never have as many ships as you’d like, but the ships you do have will generally be so good that you can even send them up against superior numbers without having to worry too much. When everyone else is fielding 25,000-ton dreadnoughts with 12 or 13 inch guns, it can be a real gut check for them to have to go up against a 36,000-ton British one with 15 inch guns and several extra inches of armor. If you keep such a ship out of the range of enemy torpedoes (read: avoid night battles if at all possible), it can be very, very hard for anyone to take it down.

There is one thing to be wary of, however. To reflect the real-world British experience at the Battle of Jutland — at which Admiral David Beatty, after watching three British battlecruisers explode spectacularly upon being hit due to insufficient protection against fires reaching their internal stockpiles of shells, exclaimed “there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today” — the game occasionally throws unseen weaknesses into the British player’s ship designs, which can lead in battle to catastrophic failure. (Once as the U.S. player I was forced to take one American dreadnought into what seemed a hopeless battle with four British, only to watch in astonishment as three of the British capital ships blew into smithereens one after the other.) There’s not really anything you as the player can do to defend against this, and how pervasive these flaws are aren’t documented anywhere; all you can do is be aware they exist, and that even the most impressive, modern class of battleships in your fleet could turn out to have an Achilles’ heel.

Germany

The German player starts off the game in a moderately awkward position.

In 1900, she has what appears to be an impressive network of overseas possessions, ranging from the west coast of Africa through the Indian Ocean to Southeast and Northeast Asia. However, when you look more closely at these, you quickly realize that these bases are all too small to support operations by battleships, or really anything larger than a single armored cruiser. But if you want to keep them, you have to protect them — so you have to find a way to get them into shape before another power with better basing in that sea zone comes along and takes them off your hands.

What’s worse, the legacy fleet you usually start the game with isn’t set up to defend those overseas possessions even if you want them to. You usually start with a few battleships, but they’re frequently battleships with short range and cramped accommodations; such ships can’t operate effectively too far from a large base, and in wartime short-range ships can’t transit through sea zones occupied by enemy ships at all. So if all you’ve got is short-range battleships, and you haven’t pre-positioned any of them in, say, Southeast Asia before war is declared, they’re simply never going to get there until the shooting stops again; too many enemy fleets lie between Germany’s home bases in the North and Baltic seas and the German bases in the Bismarck Archipelago and Caroline Islands for such a transit to be practical.

So if you want to hold on to all those colonies, at game’s start you have a lot of building to do, and in two directions at once. First, you have to be building ships with the range to make the kind of oceanic voyages you’ll need them to make in wartime — and that can mean spending the game’s first decade deferring getting into new-fangled ship types like dreadnoughts and battlecruisers in order to build up longer-ranged conventional ships. And while you’re doing that, you also need to be building up the naval bases at your possessions overseas so they are big enough to receive and support those ships once they arrive; and even if you limit that building program to one single base in each sea zone, that’s four bases you’ll need to put through a program of expansion that will take years and consume many millions of marks.

But despite the network of useless colonies it has built up, Germany remains in 1900 a continental empire, which means that maintaining those colonies could be argued to be secondary to the protection of German home waters. And in the game’s Northern Europe sea zone, which is where those home waters lie, you face powerful opponents: Britain, France and Russia, all of which are strong enough to pose a credible threat at the game’s opening. So now, alongside all that building you have to do to make those colonies defensible, you also have to be building up a fleet in the North Sea that can at least prevent those powers from putting you under blockade. And you have to do all this with a limited budget, less advanced technology, and a mercurial Kaiser.

(In the real world, the architect of the German Navy, Alfred von Tirpitz, didn’t even try to square this impossible circle. Instead, he promoted a mission for the fleet based on what he called “risk theory.” Risk theory argued that the Germans didn’t need to have a battle fleet large enough to overwhelm the main naval power in Northern European waters, the British; they just needed a fleet that was large enough to damage the British fleet so severely that it would be unable after a clash to meet its requirements around the world. Tirpitz argued that the simple possibility of such an outcome would deter the British from ever confronting Germany at sea. As it happened, this theory turned out to be completely wrong; having plowed so much money into its own battle fleet, it was the Germans who when war came shied away from a confrontation which could see that investment humiliatingly sent to the bottom of the sea.)

Despite all that, though, Germany comes into the game with some distinct advantages as well. If you’re willing to abandon your colonies, for instance, you can narrow the list of sea zones that Germany has to care about down to just one — Northern Europe — which means you really can build up a fleet that can challenge the British there, especially if they have to cover their overseas possessions too. While your guns will generally lag behind those of British and American ships in terms of caliber, they will often be of higher quality, letting those smaller guns hit more reliably and fail less often. And while your budget starts off limited, as the game goes on it’s one of the few that can grow large enough to keep up with those of the British and Americans. (Who, if you’re lucky, will at some point go to war with each other, letting you watch from the sidelines as your two biggest threats whittle each other down.)

Unlike many powers, Germany is also ideally positioned to make use of submarines. Submarines are useless as oceanic combatants, as their range is too limited to range beyond your home waters and they don’t count towards the tonnage requirements you have to keep on station at your overseas possessions. But they can be absolutely deadly off your home coasts, especially later in the game when the rickety, unreliable submersibles of 1900 have become the swift, deadly raiders of 1915; and since your home waters are also the home waters of your most dangerous enemies, a fleet of submarines can wreak havoc both on their shipping and on their battle fleets.

And, if you decide you really do want to fight for a colonial empire, opportunities can present themselves there as well. If you build up your foreign bases and build out ships with the range to reach them, it can be possible to mass enough force in one sea zone to permit your army to land at your opponent’s bases there, seizing them. France, Britain and the United States have lots of colonies in Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean and West Africa; if you’re nimble, you can mass in one of those zones and overwhelm some of those colonies before your opponent can gather enough force to drive you out. (This can have a virtuous-circle effect, too; when you capture an enemy colony you capture its naval base too, so capturing colonies can be just as effective a way to increase the size and number of ships you can operate in a sea zone as building up your existing bases there is.)

So: Germany’s position is awkward, but it’s not impossible, and at least you have options.

Japan

Japan doesn’t have a lot of options.

In 1900, Japan is a second-tier naval power at best. In your own home waters of Northeast Asia you can face direct opposition by both Russia and Germany; your only overseas possessions are in Southeast Asia, where you can potentially run into conflict with Britain, France and the U.S. Your fleet is small, your budget is smaller, and your domestic shipyards can only build vessels up to 10,000 tons, which means that if you want to build a battleship you have to pay a foreign shipyard to do it for you. You can build up your own yards to a size where you can do your building locally, but doing so takes time — as with expanding naval bases, each round of improvements to your shipyards takes a year to complete — and unless you’re building out your yards very aggressively, you’re always going to be running behind the capacity of the first-tier powers.

All of which sounds pretty limiting, I know. But we know that, in the real world, Japan managed to build up sufficiently just a few years after 1900 to crush the Russians at sea in a war that dramatically established them as a naval power to be reckoned with. Can a Japanese player do the same in RtW?

The answer is yes. Japan has limitations, but it also has important advantages.

The first is positional. Unlike the Great Powers, you as the Japanese player have no globe-spanning network of colonies; but that can actually be a source of strength, because it means you can completely abandon the need to build a large enough fleet to meet any possible enemy anywhere in the world. All you need to care about is being strong enough in two sea zones — Northeast and Southeast Asia — to handle whatever forces the other powers station there. Additionally, since these sea zones are far from the home waters of most of the colonial powers, what you’re generally going to be facing there is second-line stuff, old cruisers and pre-dreadnought battleships and the like; Britain and Germany and France will all want to keep their cutting-edge ships closer to home for the purpose of fighting each other. Finally, that great distance means that, if you can overcome whatever forces they have on station when the shooting starts, it can take many months for them to sail reinforcements out to meet you; months that you can use to seize their bases, disrupt their merchant fleets, and generally make hay while the sun shines.

Since your home waters are just one sea zone away from Southeast Asia, of course, all of those positional problems are flipped on their heads for you. You can focus your limited resources on building enough ships to be competitive in just the two sea zones you care about, rather than having to disperse forces across the world’s oceans. You can concentrate powerful, modern forces in your two zones without having to worry about potential foes elsewhere. You can move forces between these two zones in just one month’s time, making you agile and hard to pin down.

In other words, so long as you can limit your ambitions to Asian waters, you can punch far above your weight.

You have some other advantages as well, including a special ability that only the Japanese possess; when war breaks out, if you and the opponent have fleets in the same sea zone, you can launch a night-time surprise attack that will catch the enemy fleet at anchor. While their ships are frantically trying to raise steam and get to battle stations, they are stationary and unable to fight back effectively; your ships, meanwhile, are sailing at full speed with decks cleared for battle. There are no guarantees that you will win this battle — fighting at night is difficult in this pre-radar era, wandering too close to the anchored enemy can result in your ships getting hit by torpedoes, and once the enemy is alerted and moving the advantages surprise gives you are gone. But it certainly lets you enter battle with your opponent severely handicapped; and if you’ve built wisely and can handle your ships effectively, you can take advantage of those handicaps to deal a devastating blow.

France

France starts the game in what seems like a good, strong position. It has bases around the world, a respectable legacy fleet, and a decent naval budget. But its strategic position is undermined by a fatal problem — the same fatal problem that made France a negligible naval power during this period in the real world as well.

That problem is France’s geography. Having both Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts, simply protecting her home waters requires maintaining two separate fleets; and these fleets each share waters with regional enemies strong enough to take on a fractional French fleet with reasonable hope of success (Germany in the Atlantic/North Sea, Italy in the Med). Concentrating to face one, however, leaves the other wide open. And France’s far-flung colonies need protection too, of course. If France had the resources of, say, the United States, she might be able to deal with this strategic incoherence simply by throwing money at it; but she doesn’t, so her strategy becomes a series of unenviable choices, of robbing Peter to pay Paul.

And then of course there is France’s traditional enemy, lurking right across the English Channel: Great Britain. Unlike France, Britain has the resources to maintain strong fleets in both the Northern Europe and Mediterranean sea zones, as well as to guard her overseas empire. And while in the real world Britain and France, both struggling to keep up with the pace of German naval construction, eventually came together in alliance to meet the threat together, there’s no guarantees of such a rapprochemont emerging in RtW. For all you as the French player know, it may be Britain and Germany teaming up, which from the French perspective is pretty much an apocalyptic scenario.

All of which locks France inside a puzzle box that it’s not clear how to open. If you try to abandon either the Mediterranean or Northern Europe sea zone to concentrate your strength in the other, you’ll quickly receive a tongue-lashing (and an accompanying prestige loss) from the civilian government, which has yet to come to terms with just how far France’s ambitions have outstripped her means. Pulling back from the colonies means losing them when war breaks out, or watching your prestige erode further as complaints from colonists and merchant mariners that you’re not protecting their supply routes pile up. You can try to build up a large enough fleet to meet the German threat, but you simply do not have the resources to meet every threat in every theater.

France is the first power on this list whose handicaps are sufficiently great to make it difficult to identify any really good strategy to overcome them. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t play as France, of course; struggling to overcome challenges is what makes a strategy game fun, after all. It does mean, however, that the powers on this list from this point on are best left to advanced, experienced players looking for something to really test their strategic mettle.

Russia

On paper, Russia looks like it should be a pretty formidable power in RtW. It starts you off docks nearly as large as those of England and France, a naval budget that’s in line with up-and-coming powers like the U.S., and a strong legacy fleet that includes a respectable number of battleships. If you play with an historical distribution of natural resources, Russia is even one of the few powers that has access to oil right from the start of the game, letting you switch from coal-fired ships to faster, lighter oil-fired ships as soon as you can get your hands on the technology to do so.

You may have noticed, however, that Russia is pretty far down this list. And that’s because, in RtW as in the real world, Russian naval power in 1900 is more or less a Potemkin village.

The handicaps Russia labors under are many and serious. You start with a healthy naval budget, but Russia’s failure to industrialize during this period means that it stays stagnant as other powers’ coffers swell. Russia’s backwards educational system and lack of naval expertise means that research pays off less and more slowly for you than it does for your rivals, which in turn makes your advantages in natural resources harder to tap; who cares if you have oil wells if you have no idea how to build an oil-fired ship?

Beyond cultural challenges, there are geographic ones to grapple with as well. Like the U.S., you have to split your fleet to defend two distant coasts, Northern Europe and Northeast Asia, simultaneously; but unlike the U.S., you have strong rivals right on your doorstep in each of those zones, and there’s no canal coming to cut down the length of the voyage required for ships to transfer from one to the other.

What’s worst of all, though, is the way these handicaps interlock to reinforce each other. You need to get your prestige up to get your budget increased, but to keep it up you need to win battles, and you can’t win battles with obsolescent ships that have to sail for half a year just to reach the battle zone. You need to increase your research spending to field ships that are competitive, but the game caps research spending at 10% of your overall budget, which means going beyond that requires increasing your budget; but that requires increasing your prestige, which, see above. When you turn from one problem you just encounter another.

If you’re playing as Russia, then, the key to getting to some kind of successful-looking conclusion is to be modest in your ambitions. Husband your fleet; don’t send it off to bravely confront enemy fleets if you can avoid doing so, keep it in port so it can at least stop your opponent from being able to put you under blockade. Your lack of overseas possessions can be a positive here — it means fewer flashpoints that can bring you into collision with better-equipped powers. You’ll never be able to take on Britain directly, so focus on Germany in Northern Europe and Japan in Northeast Asia.

Submarines can be useful, even though your subs will never be cutting-edge technically; the same is true of long-range commerce raiders, which can disrupt your enemy’s trade networks (building up political pressure on them back home to end the war). Your surface raiders are going to lag technologically too, though, so concentrate on making them fast and cheap — they’re going to get run down by more capable ships from time to time, so the extra speed can help them get out of danger, and making them cheap means you can afford to lose some without breaking the bank.

It’s not a great strategy, but then Russia doesn’t really have access to a lot of great strategies. You have to work with the materials you have.

Italy/Austria-Hungary

I’m grouping Italy and Austria-Hungary together on this list, because they both have more or less the same strategic position.

These nations are Mediterranean powers only. They can muster fleets that are strong and capable enough to guard their interests inside that inland sea, but that’s about it. Italy has just one overseas possession outside the Med, a naval base in the Indian Ocean at Eritrea that’s too small to support battleship operations; Austria has no overseas possessions whatsoever.

What this means in practice is that these two powers are each others’ natural enemies. There are plenty of possessions inside the Mediterranean sea zone that they can both dream of seizing; Italy has respectable bases in Sicily and Sardinia, Albania, Rhodes and Libya all start the game independent, and even France’s four bases can become targets if France gets tied down fighting strong opponents elsewhere.

Expansion outside the Mediterranean, though, is difficult at best. Italy’s tiny base in Eritrea provides what seems like a starting point; but its small size and Italy’s inability to field powerful fleets in the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean simultaneously mean that it’s frequently snapped up by other powers.

Austria lacks any such springboard altogether. It’s possible for them to obtain one via random events or some other freakishly lucky chance, but then she has the problem of defending these new holdings, which is difficult at best for a nation with an undersized fleet. Of all the powers in the game, Austria starts the farthest behind in shipbuilding — while her dockyards are able in 1900 to build ships up to 13,000 tons, the ships of her legacy fleet are almost comically small, with “battleships” so small that in any other nation they would be designated as armored cruisers. You can build up new, larger ships, but that takes money you probably don’t have and time your opponents may not be inclined to allow you.

In this respect, if Austria can be said to have any advantage, it’s a simple one: her naval presence is so small that it’s unlikely to attract much hostile attention. There are no Austrian colonies for other powers to eye greedily, no Austrian dreadnoughts standing in the way of some important supply line. Italy, while weak, can in at least some circumstances contemplate challenging larger powers like France; if Austria is to grow, it will have to be at the expense of the only power she can challenge on anything like similar terms: Italy.

If I was going to be stranded on a desert island for the rest of my life and could only take one book with me, I’m not 100% certain which one I’d pick. But I am 100% certain that Stephen Mitchell’s Tao Te Ching: A New English Version would be on the short list. It is one of the very few books I’ve read that legitimately changed my life.

If I was going to be stranded on a desert island for the rest of my life and could only take one book with me, I’m not 100% certain which one I’d pick. But I am 100% certain that Stephen Mitchell’s Tao Te Ching: A New English Version would be on the short list. It is one of the very few books I’ve read that legitimately changed my life. Like many others, I was surprised when I woke up this morning to discover that

Like many others, I was surprised when I woke up this morning to discover that  There’s been a lot of coverage over the last week to findings by The Intercept that Chris Kyle, legendary Navy SEAL and famed author of the bestselling book American Sniper,

There’s been a lot of coverage over the last week to findings by The Intercept that Chris Kyle, legendary Navy SEAL and famed author of the bestselling book American Sniper,  I’ve written in this space before about my love for Rule the Waves,

I’ve written in this space before about my love for Rule the Waves,  Just a quick note to tell you about a good little movie you should check out: 2014’s

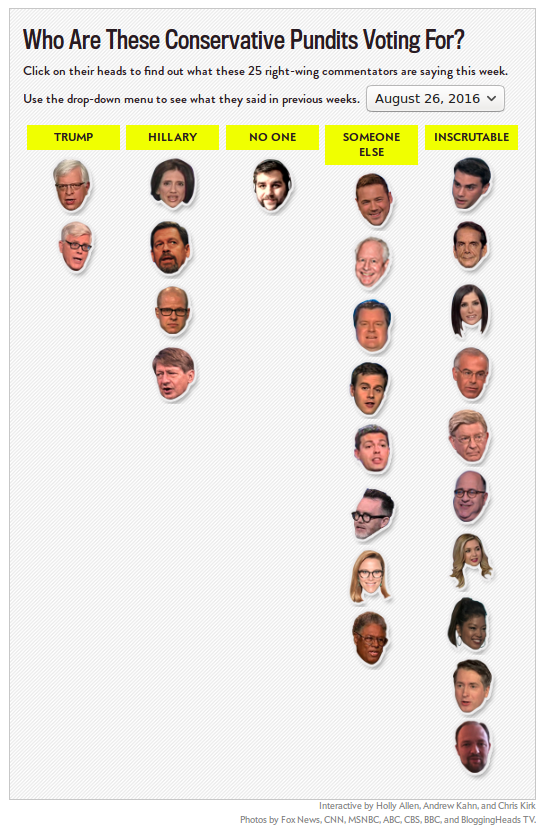

Just a quick note to tell you about a good little movie you should check out: 2014’s  Now that Donald Trump has pulled out into a strong lead in the GOP presidential primaries, it might seem like he has a lock on that party’s nomination. But party leaders and other dissatisfied Republicans, desperate for a way to keep that from happening, have started talking about doing something that hasn’t happened in American politics in a long, long time: putting up a fight against him at the party’s nominating convention, regardless of how many votes he’s won. This would produce what’s known as a “brokered” or “contested” convention.

Now that Donald Trump has pulled out into a strong lead in the GOP presidential primaries, it might seem like he has a lock on that party’s nomination. But party leaders and other dissatisfied Republicans, desperate for a way to keep that from happening, have started talking about doing something that hasn’t happened in American politics in a long, long time: putting up a fight against him at the party’s nominating convention, regardless of how many votes he’s won. This would produce what’s known as a “brokered” or “contested” convention. The Virginia Democratic primary is tomorrow, March 1, so I just thought I’d take a moment to let you know that I’ll be voting for Bernie Sanders.

The Virginia Democratic primary is tomorrow, March 1, so I just thought I’d take a moment to let you know that I’ll be voting for Bernie Sanders.

I’ve

I’ve

I want to tip you off to something really good I came across while digging through Netflix’s catalog the other day. It’s a 3-episode miniseries called

I want to tip you off to something really good I came across while digging through Netflix’s catalog the other day. It’s a 3-episode miniseries called  I’ve never really been a comics nerd. (I’m certainly a lot of other kinds of nerd, just not that kind.) I read ’em as a kid, of course, so I know enough to know who the Avengers are and that Aquaman sucks. But I lost interest in them in adolescence and never really came back, so I missed out on their remarkable creative efflorescence over the last twenty years or so.

I’ve never really been a comics nerd. (I’m certainly a lot of other kinds of nerd, just not that kind.) I read ’em as a kid, of course, so I know enough to know who the Avengers are and that Aquaman sucks. But I lost interest in them in adolescence and never really came back, so I missed out on their remarkable creative efflorescence over the last twenty years or so. Dear Jack,

Dear Jack,

It’s been a little more than fifteen years now since I was first diagnosed as

It’s been a little more than fifteen years now since I was first diagnosed as

This will just be a brief note on strategy. Nobody ever reads these and they never change anything, so I have no idea why I still bother, but here we go anyway.

This will just be a brief note on strategy. Nobody ever reads these and they never change anything, so I have no idea why I still bother, but here we go anyway.

After I rolled out

After I rolled out  The JWM Summer of Fiction hit a bit of a snag over the last couple of weeks, due to some unexpected personal difficulties. But those are now (more or less) resolved, so I can finally get around to posting the last review: Hilary Mantel’s 2009 Man Booker Prize winner, Wolf Hall.

The JWM Summer of Fiction hit a bit of a snag over the last couple of weeks, due to some unexpected personal difficulties. But those are now (more or less) resolved, so I can finally get around to posting the last review: Hilary Mantel’s 2009 Man Booker Prize winner, Wolf Hall. The HBO miniseries

The HBO miniseries