The question about bombing Iran that nobody is asking

Posted on March 9, 2012

There’s been a lot of loose talk lately about either Israel or the U.S. launching an air attack on Iran in the near future to degrade or cripple that country’s nuclear program. Nitwitted Republican Presidential candidates casting about for a way to look macho and idiot pundits who never saw a war they didn’t like (as long as it doesn’t cost them anything personally) have latched on to this idea with a vengeance. And while it would be bad enough if such talk were confined to those quarters, it’s been quietly seeping into the mainstream as well.

There’s been a lot of loose talk lately about either Israel or the U.S. launching an air attack on Iran in the near future to degrade or cripple that country’s nuclear program. Nitwitted Republican Presidential candidates casting about for a way to look macho and idiot pundits who never saw a war they didn’t like (as long as it doesn’t cost them anything personally) have latched on to this idea with a vengeance. And while it would be bad enough if such talk were confined to those quarters, it’s been quietly seeping into the mainstream as well.

There’s been some pushback on the idea, thankfully. President Obama has spoken out against it, for example, which is heartening. But most of the counterargument has been based on the premise that taking out Iran’s nuclear facilities with air strikes would either be counterproductive, hardening Iranian resolve, or that it’s simply not necessary because Iran’s nuclear program isn’t as far along as the hawks fear it is.

Those things may or may not be true, I have no idea. But there’s one question about an attack that nobody on either side of the question appears to be asking, and that’s disturbing, because it’s probably the most important question that could be asked. That question is whether or not we even have the capability to take out Iran’s nuclear facilities from the air.

The History

First, some history. The pattern for an attack like this was set in 1981, when the Israelis launched an air strike to take out a nuclear reactor the Iraqis were in the process of setting up, known as “Osirak.” Since Israel and Iraq were not at war and it wasn’t clear that the purpose of the Osirak reactor was actually military, the raid provoked a firestorm of controversy around the world, but it achieved its strategic purpose — the reactor was destroyed, and a setback was dealt to Iraq’s nuclear ambitions which they never really came back from. Advocates for a strike on Iran point to the Osirak raid as an example of how Iran could be curbed.

But here’s the thing: the situation in Iran in 2012 is very different than it was in Iraq in 1981. The Iranians may be fanatics, but they’re not stupid; they paid close attention to the lessons of Osirak when they set up their own nuclear program. So unlike Osirak, which was built out in the open air, Iran’s nuclear facilities are buried deep underground — so deep underground that it’s not clear that they can be reached by even the most powerful conventional bombs.

The Targets

To see what I mean, look at two of the key Iranian nuclear facilities. (Detailed information on them is understandably hard to come by, but we can get at least a general understanding of their construction from unclassified sources.)

The first is the uranium enrichment facility at Natanz. This facility houses thousands of the gas centrifuges that are required to turn raw uranium into nuclear fuel for either civil or military purposes. Unlike Osirak, the Natanz facility is a “hardened target” — a target built specifically to be difficult to destroy with bombs. It was built somewhere around thirty feet underground, with walls of reinforced concrete designed to buffer shock from explosions.

The second is a newer facility in northern Iran, near the village of Fordo. Even less information is available in the public domain about this facility than about Natanz, since the Fordo facility was only revealed publicly by Iran in 2009. However, even with this limited information it’s clear that Fordo is designed to be an even tougher nut to crack than Natanz. The Fordo facility was built directly into a mountainside, possibly hundreds of feet deep, with even thicker layers of protective concrete. Unlike Natanz, which has enough centrifuge capacity to create fuel for either civil or military purposes, Fordo has much more limited capacity; this limits its utility in creating fuel for civilian energy projects, but not necessarily for producing uranium for weapons.

(Despite Fordo’s hardened construction, its design is believed to still have points of weakness to air attack; Iran has started moving to remove those, and to prepare Fordo for the installation of new centrifuges. This is what has reignited discussion of a pre-emptive strike — the argument is that the facilities have a “window of vulnerability” that is rapidly closing, so if there’s going to be an air strike it’s now or never.)

The Weapons

When the Israelis destroyed the Osirak reactor, they used conventional air-dropped 2,000-pound bombs. Weapons such as these would be completely ineffective against hardened targets like Natanz and Fordo, however; their explosive payload is simply insufficient to dig through so much dirt and concrete. What would be needed is a much more powerful bomb that is designed specifically to channel its blast down deep, rather than exploding in all directions like a normal bomb does. This type of weapon is known as a “bunker buster.”

Israel and the U.S. both possess bunker-buster weapons, though in different amounts and sizes. Both nations have stocks of the GBU-28, an air-dropped, laser-guided bomb that can be armed with a bunker-buster warhead such as the 2,000-pound BLU-109 and the 5,000-pound BLU-113. The largest Western conventional bunker-buster bomb, the huge 30,000-pound GBU-57 (a.k.a. “Massive Ordnance Penetrator,” or “MOP”) is only in the U.S. arsenal, not Israel’s; this is in part because it’s a very new weapon, with deliveries to the U.S. Air Force starting just last year, and in part because Israel has no aircraft big enough to carry it even if we made it available to them — while the GBU-28 can be carried on small fighters like the F-15, the GBU-57 can only be carried in the B-2 stealth bomber.

The Problem

The problem with using these weapons to take out Natanz and Fordo is three-fold.

The first problem is that while the BLU-109 and BLU-113 warheads that Israel has access to are powerful weapons, it’s not certain that they are actually powerful enough to blast through the thick layers of earth and concrete surrounding Natanz and (especially) Fordo. A strike with these weapons might destroy the facilities; but then again, it might not. (The BLU-109, for instance, is rated to penetrate around six feet of concrete — but even at the less heavily hardened Natanz facility, you’re looking at thirty-plus feet of earth, along with an unknown number more of concrete.) It might just put some cracks in concrete and throw a bunch of dirt around. And for Israel, that would be a worst-case scenario; if you’re going to hit a nation you’re not already at war with, that hit needs to be so overwhelming and successful that the enemy decides retaliation is pointless. Otherwise you get the Pearl Harbor problem — an aroused and angry opponent who you haven’t completely knocked out of the ring.

(A 2006 study of the problem by researchers at MIT’s Security Studies Program argued that Israel could have high confidence of taking out Natanz with BLU-113s, but only in a large-scale strike involving 80+ warheads — a much larger and more complex operation than the Osirak raid, which involved only sixteen bombs.)

The second problem is that the only conventional bunker-buster that would offer a high probability of destroying the targets is the gigantic GBU-57, and the Israelis don’t have that weapon — only the U.S. does. So if the Israelis want to strike Iran, their options are either to go it alone and risk the possibility that their own weapons are insufficient for the task, or to go in with the U.S. and risk whatever conditions and terms we would put on the conduct of the operation.

The third problem is that even the Massive Ordnance Penetrator might not be quite massive enough to destroy a facility like Fordo. When deciding whether or not to run risks of war, political leaders understandably strive for certainty; they want to know that the risk of the operation failing is as close to zero as it can possibly be. And the Iranian facilities are so dug-in that even the MOP doesn’t offer that certainty. The MOP is a gigantic weapon, and it stands a better chance of penetrating the walls of Natanz and Fordo than the smaller bunker-busters do; but it’s never been used in battle before, so it’s always possible that there’s some problem with it that nobody foresaw, and there’s less than 20 of them in the Air Force’s kit bag currently, so if it turns out that it takes multiple MOPs to clean up the targets the bag can empty out pretty quickly. (Don’t forget that Iran may have other secret sites that we don’t know about; it would accomplish little to destroy Natanz and Fordo if they reveal a backup site the next day and we don’t have the ordnance to take out that one too.)

There’s a more ominous way to think about that third problem, too. The MOP is our biggest conventional bunker-buster, and even it might not be big enough, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have weapons that we could be certain are big enough to destroy these facilities. The problem is that those weapons are nuclear weapons. An attack with “nuclear bunker-busters” could deploy many times the explosive weight of even the largest conventional bombs. The problem there is, well, you’ve just used nuclear weapons in anger for the first time in world history since the end of World War II, and that opens up a whole new can of worms. (Not to mention that Fordo is near the Shia holy city of Qom; you can imagine the outcry if that city were to become collateral damage in an American nuclear attack.)

The Conclusion

I should preface this by saying that all the above information could be completely invalid. It’s possible that either we or Israel have classified weapons in our arsenal that would make an attack much more likely to succeed, and that these are just so deeply secret that a layman like myself doesn’t know about them. It’s also possible that there’s a particularly brilliant tactical approach to this problem that works around the problems and hits the Iranians in some undisclosed blind spot that a dumb civilian like myself would never see. And the men and women of the IAF and U.S. Air Force are among the world’s most elite practitioners of aerial warfare, so if anyone can pull off the unlikely, they can.

However, putting all that aside, the weight of the problems and uncertainties outlined above make me extremely skeptical that an air strike (or a series of air strikes) is the way to try and resolve this problem. Put bluntly, it seems like the probabilities of it causing new problems are higher than the probabilities of it solving the old ones.

My guess is this is why, while politicians are waxing rhapsodic about how we can bomb our way to a non-nuclear Iran, professional soldiers are being a bit more circumspect. General Norton Schwartz, the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, for instance, who is sounding pretty skeptical:

“Everything we have to do has to have an objective,” Schwartz told reporters at a breakfast meeting Wednesday. “What is the objective? Is it to eliminate [Iran’s nuclear program]? Is it to delay? Is it to complicate? What is the national security objective?”

“There’s a tendency for all of us to go tactical too quickly, and worry about weaponeering and things of that nature,” Schwartz continued. “Iran bears watching” is about as far as the top Air Force officer was willing to go.

As is the chairman of the Joint Chiefs:

“It’s not prudent at this point to decide to attack Iran,” said Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff…

“A strike at this time would be destabilizing and wouldn’t achieve their long-term objectives,” Dempsey said about the Israelis, according to Bloomberg. “I wouldn’t suggest, sitting here today, that we’ve persuaded them that our view is the correct view and that they are acting in an ill-advised fashion.”

This isn’t to say that there aren’t things we can do to hinder Iran’s nuclear ambitions. There’s increasing evidence that last year’s Stuxnet computer virus, which infected computers around the world, was actually a clever cyberattack on the computers that run the centrifuges at Natanz, for example; if that’s the case, it would be a brilliant example of thinking outside the box, avoiding the need to dig through dirt and concrete by creating a weapon that an unwitting Iranian engineer would carry right through the front door on a USB stick. And there’s low-tech countermeasures that can be taken as well, as somebody has been quietly demonstrating by arranging a series of “accidents” to happen to Iranian nuclear scientists.

In other words, espionage and spycraft may be the prudent decisionmaker’s weapons of choice here, rather than big bombs and fast jets. Maybe they don’t provide a big enough testosterone rush for the likes of Newt Gingrich, but they make pills that can help with that. (Ask Bob Dole, he can hook you up.) A rational policymaker, however, needs to make decisions based on what military power can realistically achieve, not on juvenile fantasies of unlimited power.

One would think the last ten years would have taught America’s leaders that lesson pretty clearly. Or hope, anyway.

There’s been a lot of loose talk lately about either Israel or the U.S. launching an air attack on Iran in the near future to degrade or cripple that country’s nuclear program. Nitwitted Republican Presidential candidates casting about for a way to look macho and idiot pundits who never saw a war they didn’t like (as long as it doesn’t cost them anything personally) have latched on to this idea with a vengeance. And while it would be bad enough if such talk were confined to those quarters,

There’s been a lot of loose talk lately about either Israel or the U.S. launching an air attack on Iran in the near future to degrade or cripple that country’s nuclear program. Nitwitted Republican Presidential candidates casting about for a way to look macho and idiot pundits who never saw a war they didn’t like (as long as it doesn’t cost them anything personally) have latched on to this idea with a vengeance. And while it would be bad enough if such talk were confined to those quarters,

It’s starting to look like I need a new cellphone. My current one is two and a half years old now, and while it’s served me well, the hardware is starting to fail in various minor but annoying ways. And since we don’t fix things anymore, that means it’s time to go cellphone shopping.

It’s starting to look like I need a new cellphone. My current one is two and a half years old now, and while it’s served me well, the hardware is starting to fail in various minor but annoying ways. And since we don’t fix things anymore, that means it’s time to go cellphone shopping. Today’s Web blackout against the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA)

Today’s Web blackout against the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) The New York Times’ ombudsman, Arthur S. Brisbane, asks today

The New York Times’ ombudsman, Arthur S. Brisbane, asks today  It’s the end of another year, and that means it’s time for a look back at the year’s best posts here at Just Well Mixed.

It’s the end of another year, and that means it’s time for a look back at the year’s best posts here at Just Well Mixed. Since

Since  The most recent release of Ubuntu Linux, Ubuntu 11.10, included a big change — a shift from the standard GNOME desktop environment to a new one, called Unity. (If you’re not familiar with it,

The most recent release of Ubuntu Linux, Ubuntu 11.10, included a big change — a shift from the standard GNOME desktop environment to a new one, called Unity. (If you’re not familiar with it,

It’s the day after Thanksgiving again, and that means it’s time for this year’s spate of “Black Friday” horror stories as the retail sector and the media whip shoppers into a frothing frenzy and then profess to be shocked! shocked! as those shoppers proceed to fold, spindle and mutilate one another in a mad stampede to save fifteen cents.

It’s the day after Thanksgiving again, and that means it’s time for this year’s spate of “Black Friday” horror stories as the retail sector and the media whip shoppers into a frothing frenzy and then profess to be shocked! shocked! as those shoppers proceed to fold, spindle and mutilate one another in a mad stampede to save fifteen cents. You’ve probably heard already about how the

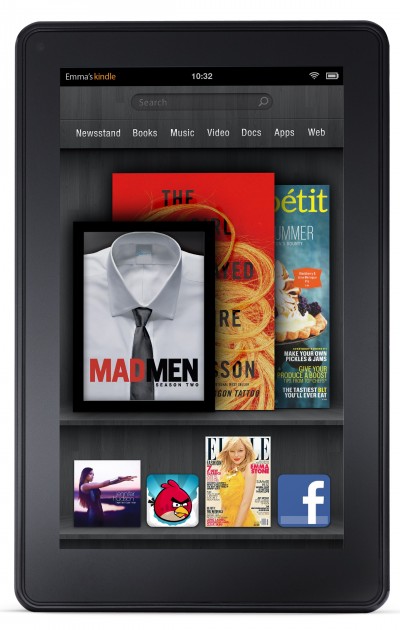

You’ve probably heard already about how the  Since Amazon has moved up the shipping dates of their new generation Kindle e-readers — the tablet-ish Kindle Fire ships today, with the new eInk Kindles following tomorrow — this seems like as good a time as any for me to explain why I refuse to buy one.

Since Amazon has moved up the shipping dates of their new generation Kindle e-readers — the tablet-ish Kindle Fire ships today, with the new eInk Kindles following tomorrow — this seems like as good a time as any for me to explain why I refuse to buy one.

“Waiter, this food is terrible! And the portions are so small!”

“Waiter, this food is terrible! And the portions are so small!” I want to talk about something that’s looming in the not-so-distant future that could kill a whole bunch of the most promising online businesses: metered billing for mobile data.

I want to talk about something that’s looming in the not-so-distant future that could kill a whole bunch of the most promising online businesses: metered billing for mobile data.

My recent post about Firefox problems on Linux

My recent post about Firefox problems on Linux This ought to be the top story on every news outlet in the world —

This ought to be the top story on every news outlet in the world —  In The New Republic, Evgeny Morozov has

In The New Republic, Evgeny Morozov has