There is no good reason to ever buy an inkjet printer

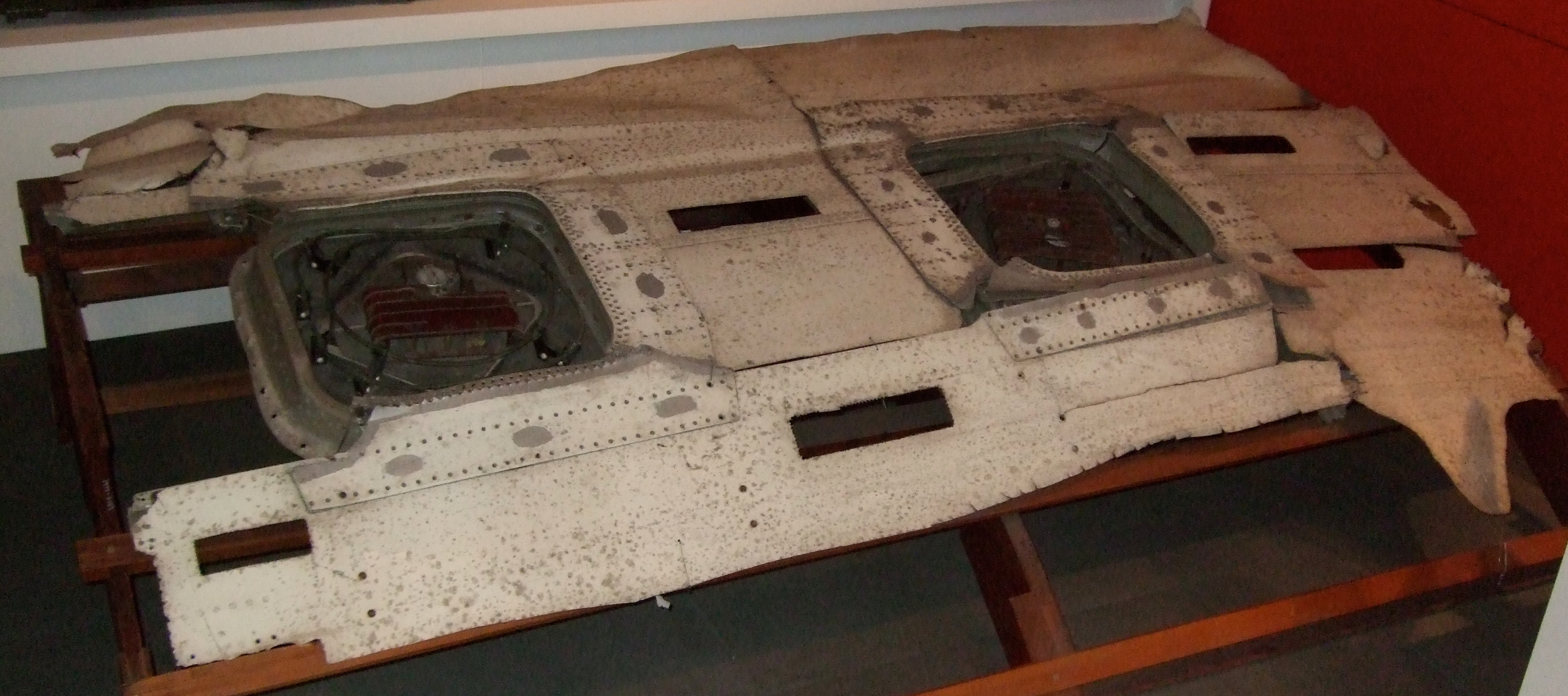

Epson 127-series (high yield) ink cartridges installed in an Epson WorkForce WF-3540 inkjet printer. Photo credit: Wikipedia user DragonLord. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Inkjet printers have been in the news lately, thanks to HP’s attempt to fleece their customers by pushing out an update that would cause those printers to reject third-party ink cartridges. (They were forced to backtrack on this plan by understandable consumer outrage.) Which gives me, as your nerd friend who gets asked about this stuff all the time, an opportunity to pre-emptively pass along to you a little bit of purchasing advice.

The advice is this: under no circumstances should you ever buy an inkjet printer.

This advice isn’t specifically about printers from HP; it’s about the entire category. Despite their enormous popularity, inkjet printers are always a bad deal.

Inkjets became popular in the 1990s as a middle ground between laser printers, which produced superior output but were then very expensive, and dot matrix printers, which were loud and ugly but cheap. Back then, inkjets gave home and small-busines users an affordable way to produce printed documents that, while still a bit rough-looking, were at least better than what they could have gotten before.

But that was twenty years ago, which is a long time in computer-world, and today the landscape of printer options is very different. Dot matrix printers, which were everywhere in 1990, have completely disappeared. And laser printers, which in 1990 were huge, colossally expensive machines only suitable for large offices, have plummeted in price and size to a point where they’re nearly as cheap as their inkjet cousins.

Which changes everything, because literally the only thing that inkjets had going for them was the fact that they were massively cheaper than lasers. They lose on every other front. Laser-printed documents are so much sharper and clearer than inkjet-printed ones that it’s silly to even compare the two. Inkjet printing uses, well, ink, which means that if an inkjet-printed document gets wet the ink can blot and run; laser-printed documents don’t have this problem.

And then there is the big problem with inkjets, which is that ink for them is just ludicrously expensive. Printer makers have taken advantage of the fact that inkjet buyers tend to be less technically savvy for decades, luring them in with cheap printers and then gouging them on ink. The result of all that gouging is that, ounce for ounce, printer ink these days costs more than Chanel No. 5. For the same amount you’d spend on a gallon of ink, you could buy more than 2,600 gallons of gasoline! That’s ridiculous.

Today’s laser printers, on the other hand, are cheap, efficient and reliable. You’ll pay a little more up front to buy the printer, but not that much; you can get a very capable black-and-white laser these days for around $100. (Here’s an example.) And the cost to operate that printer will be much lower. Lasers use “toner” rather than ink; a replacement toner cartridge for the printer I linked to costs around $45 and is good for 2,600 pages, which works out to just under two cents per page.

Compared to that, an HP black ink cartridge may seem cheaper, since it’s priced at around $14; but it’s only good for 190 pages (!), which means you’re paying more than seven cents for each page you’ll get out of it. That’s more than four times as much as what that page would cost you to produce with a laser. Or, to put this slightly differently: a $14 ink cartridge is no bargain when you’d have to buy 14 of them to print as many pages as you could print with one $45 toner cartridge.

There’s two common reasons people give for holding on to inkjets, despite this economic logic. The first is that inkjet printers are cheaper up front than lasers are. And that’s true! You can walk into a Best Buy and walk out with a basic inkjet printer for under $50. But this only seems cheaper, because while you’re saving a little money up front, you’ll end up spending lots more to keep that thirsty inkjet filled with ink. Saving $40 on the printer doesn’t gain you much if you end up spending $145 more on consumables.

The second is that they want to print in color. Even the cheapest inkjets offer color printing, while the cheapest lasers are black and white only, so at first glance this seems to make sense. Like the “cheaper up front” argument, though, it makes less sense the more you look into it.

First, while the cheapest lasers do not offer color printing, it’s certainly possible to get a color laser. You’ll just pay more for it; color lasers generally start at around $150-200 these days, and toner for them is more expensive than plain black-and-white toner.

But there’s a more fundamental problem with this argument for inkjets, namely this: you probably don’t want to print in color as much as you think you do.

Think about it. When was the last time you printed anything that absolutely had to be printed in color? Most documents are just that, documents — which is to say, mostly text, which benefits next to nothing from being printed in color versus black-and-white.

There are things that do have to be printed in color, of course; the most obvious example is photographs. But even here, the argument for inkjets fails to impress, because being able to print in color isn’t the same thing as being able to print in color well. Reproducing colors in photographs accurately demands a lot more than just some barrels of color ink; it demands a high-resolution printer and special, treated paper that can hold colors better than plain old printer paper can. You can buy that stuff too, of course, but doing so expensive and complicated, which makes it hard to recommend when you could alternately just send your photos to a photo printing service and get much better results than you’d get at home for a fraction of the price.

So take my advice: next time you’re in the market for a printer for your home or small office, don’t get fooled by the low price of inkjets. Spend a little bit more up front and get yourself a laser printer instead. You’ll get better output, save a ton of money over time, and stick it to the greedy bastards who have been gouging unsuspecting inkjet customers for years.

That’s what’s called a “win-win.”

Twitter is in trouble. The microblogging service, which is coming up on ten years of struggling to reach a mass audience, has recently admitted defeat and started looking for a buyer. And so far, the results have not been great:

Twitter is in trouble. The microblogging service, which is coming up on ten years of struggling to reach a mass audience, has recently admitted defeat and started looking for a buyer. And so far, the results have not been great:

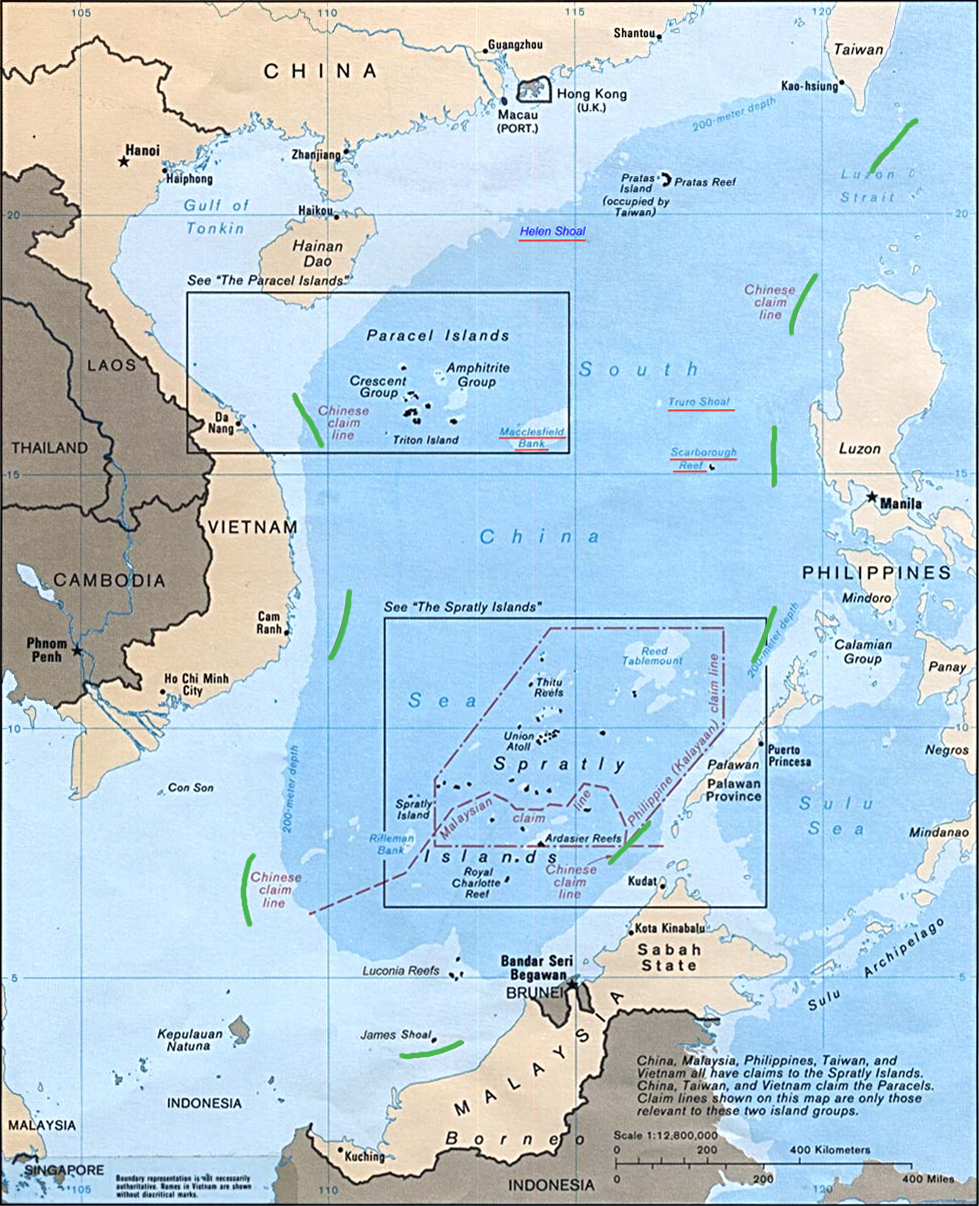

We here in the United States are in the middle of an election season, which means that our attention at the moment is focused like a laser beam on domestic problems. But the world doesn’t stop turning just because we’re not paying attention, and over the last year we’ve drifted closer to conflict with a range of other major powers than we’ve been in a long time. So this is the first post in an occasional series, “Better Know an Apocalypse,” whose purpose is to bring you up to to speed on these potentially catastrophic flashpoints.

We here in the United States are in the middle of an election season, which means that our attention at the moment is focused like a laser beam on domestic problems. But the world doesn’t stop turning just because we’re not paying attention, and over the last year we’ve drifted closer to conflict with a range of other major powers than we’ve been in a long time. So this is the first post in an occasional series, “Better Know an Apocalypse,” whose purpose is to bring you up to to speed on these potentially catastrophic flashpoints.