A well-regulated apocalypse: inside the Code of Emergency Federal Regulations

Posted on November 3, 2016

A few days ago, I mentioned that (with the assistance of the National Archives) I had unearthed a bit of Cold War history previously unavailable to the public: the Code of Emergency Federal Regulations (CEFR), a secret set of official regulations that were to go into effect in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack on the United States.

I couldn’t say much at the time about the actual contents of the CEFR, because it is a binder-full of long documents written in dense governmentese and I needed time to parse them all. But now I’ve put that time in, so I’d like to take you on a guided tour of this remarkable set of documents.

My original post includes a link where you can download the complete contents of the CEFR, and the Archives are already working on converting these PDFs into more accessible formats, so I’m not going to try and summarize every single rule to be found within them here. Instead, I’m going to call out the points that struck me as the most important and/or surprising; the things that will give you the best sense for how America’s regulatory agencies were grappling with the problem of how to deal with a mandate to lay down rules to govern a literally unprecedented situation.

As you read through these documents, you realize just how monumental that challenge was, and how variably those agencies approached what these documents call “the emergency.” Some came at it with bureaucratic gusto, laying down thick volumes of regulations to cope with any possible circumstance. Others took a simpler tack, granting sweeping powers to their leaders and establishing long chains of succession to try and ensure at least that leaders killed in the attack would be replaced. Still others did nothing, becoming conspicuous by their absence. Together they illustrate the ebbs and flows of American enthusiasm for civil defense during this period.

For context, let’s look a little at where the CEFR came from, and then we’ll dig into the documents themselves.

A brief history of the CEFR

The history of the Code of Emergency Federal Regulations begins on June 25, 1956.

On that day, an act of Congress was approved by then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower, becoming Public Law 84-619. This law (which you can read online here) gave the President the power to suspend the requirement that new regulations be published “in the event of an attack or threatened attack upon the continental United States, by air or otherwise,” and directed that

The President shall establish such alternate systems for promulgating, filing, or publishing documents or classes of documents affected by such suspensions… as may be deemed under the then existing circumstances practicable to provide public notice of the issuance and of the contents of such documents.

This mandate would not be acted upon by the executive branch until February 26, 1963. On that day, just four months after the Cuban Missile Crisis had reached its climax, President John F. Kennedy issued a series of executive orders directing various Federal agencies to “develop a state of readiness… with respect to all conditions of national emergency, including attack upon the United States.”

One of these orders, Executive Order 11093, regarded the General Services Administration (GSA). The GSA provides administrative support services for Federal agencies; a mission which, at the time, included the publication of Federal regulatory activity through the Code of Federal Regulations and its daily sister publication, the Federal Register.

Executive Order 11903 directed the GSA to

Develop emergency procedures for providing and making available, on a decentralized basis, a Federal Register of Presidential Proclamations and Executive Orders, Federal administrative regulations, Federal emergency notices and actions, and appropriate Acts of Congress during a civil defense emergency.

This order would be carried out on July 1, 1965, with the issuance of the first edition of the Code of Emergency Federal Regulations.

First edition: July 1, 1965

This first edition of the CEFR contains a prologue, titled “Explanation,” that explains why the document exists:

The Code of Emergency Federal Regulations (CEFR) is designed to provide continuity in the publication of Federal statutes and regulations during a condition of enemy attack or threatened attack. It provides a vehicle for the prepositioning of emergency measures on a stand-by basis for implementation…

The emergency measures published in the CEFR are not intended to supplant all existing law. Rather, when called into effect, these measures would amend and supplement existing law to the extent necessary to meet the emergency. The CEFR, therefore, would be used in conjunction with normal sources, such as the United States Code and the Code of Federal Regulations.

And it laid out a structure through which additional emergency regulations could be promulgated, in the event such became necessary:

In such event, a serial publication designated the Emergency Federal Register (EFR) may be issued. Documents published in the EFR would then implement by reference, amend, or supplement the material carried in the CEFR.

It then set out 21 chapters, each reserved for regulations affecting a different Federal agency, starting with the President and working all the way down to the Railroad Retirement Board.

Of these, most on initial publication were simply empty sections set aside to accommodate future regulations should any be issued. But a few departments did have some emergency regulations in place at this early date.

The Treasury Department

Chapters 12 and 12A contain “Emergency Banking Regulation No. 1,” along with several supplementary rules. It is dated January 10, 1961 and issued over the signature of Eisenhower’s Treasury Secretary (and close advisor) Robert B. Anderson.

Highlights include:

- All banks are ordered to remain open and “permit the transaction of business during their regularly established hours,” except those located “in an area which is unsafe because of enemy or defensive action, or if essential personnel or physical facilities become unavailable.”

- Banks and bank branches are given wide discretion to act on their own authority in the wake of a catastrophic attack, including operating without guidance from pre-war head offices, changing locations if pre-war facilities are rendered “wholly or partially unusable,” and making loans and borrowing money as they deem necessary.

- Withdrawals of cash are to be prohibited, “except for those purposes… for which cash is customarily used,” and even in those circumstances banks are authorized to refuse cash withdrawals if they would result in a shortage of cash on hand.

- Credit is to be frozen entirely, except in extraordinary circumstances directly related to the war effort. Checks (“and other evidence of transfer of credit”) in the amount of $1,000 or more are to be held back until Federal authority to release them has been furnished.

- Broad discretion is also provided to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, and the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare to do whatever they deem necessary to keep the financial system operational.

The Post Office Department

Chapter 15 contains several regulations related to postal operations, issued over the signature of Kennedy and Eisenhower Postmaster General John A. Gronouski.

Highlights include:

- Detailed instructions on the line of succession to the office of Postmaster General are provided, should the incumbent holder of that office be killed, and whomever ends up holding that office is vested with all the “powers, functions and duties” it would come with in happier times. Similar lines of succession are established for various Assistant Postmasters General and other high-level officers of the department.

- Surviving Post Office personnel are charged with “formulat[ing] ways and means of preventing any attempt at sabotage or subversive activities,” reporting “suspicious characters” to the nearest officer in charge, and making sure they keep the doors of their facilities locked so as to prevent sabotage.

- Postal authorities in remote locations such as Alaska, Hawaii and various U.S. overseas possessions are given authority to destroy stamps, currency, and other postal property “if, in the judgment of the military authorities, the military situation so requires.” Personnel charged with carrying out such destruction are instructed (“as far as possible”) to keep a detailed inventory of the property destroyed, and to forward copies of these inventories to their Regional Director.

- Should an executive order instituting “censorship of communications crossing the borders of the United States, or any of its territories or possessions” be issued, instructions are provided as to which postal facilities would be responsible for carrying out such censorship for the different regions of the country. As regards how censorship would be carried out that these facilities, their postmasters are told to consult instructions issued to them outside the CEFR.

- “The head of each postal installation, or, when that official is unavailable, the highest ranking official in line of succession” is authorized to “take any action the emergency demands” to keep the mail moving.

- Should a nuclear attack take place, domestic and international mail is to be restricted to “letter mail in its ordinary form, not exceeding 8 ounces in weight.” Mail from government agencies, as well as shipments of money by banks and shipments of medicines, surgical implements and other disaster relief supplies are exempted from this limitation. Letter mail will be delivered free of charge for the duration of the emergency; “no such mail shall be withheld or returned for lack of postage.”

- Registered mail, certified mail, C.O.D. mail, and special handling/special delivery services are to be suspended completely, with the same exemptions as listed above for letter mail.

- On the fifth day after any nuclear attack, postmasters in “devastated areas” are granted authority to spend up to $10,000 “for contractual services necessary to the continued operation of operating equipment” and up to $1,000 for “supplies, equipment and services.”

- Postal employees required to work overtime or on weekends “during the present war or national emergency… and for sixty days thereafter” will be paid overtime compensation if they cannot be given compensatory time off.

Civil Service Commission

Chapter 31 contains “Part M-12 — Standby Regulations For Use in a National Emergency,” laying out a range of rules for Federal workers and other civil service employees. It is issued over the signature of David F. Williams, Director of the Bureau of Management Services.

Highlights include:

- Regulations prohibiting any one person from holding multiple Federal offices at the same time “are hereby suspended for the duration of the present national emergency.”

- Agencies are given the discretion to waive requirements that workers in executive branch offices be U.S. citizens “when such exceptions are in the interest of the emergency effort.”

- A special category of “emergency-indefinite” employment is created, and all new appointments for continuing positions are to be placed into this category unless specifically exempted. The first year of employment for “emergency-indefinite” workers would be classified as a trial period, and the length of their employment would be limited to “the duration of the present national emergency and not to exceed six (6) months thereafter.”

- Positions for custodians, elevator operators, guards and messengers are to be filled exclusively with veterans, “as long as qualified veterans are available.”

- All procedures for taking “adverse actions” (punishments, such as a reduction in pay) against employees are to be suspended, with the one exception that the employee must still be provided with a written explanation of why the action has been taken.

- Personnel decisions made during the emergency will not be subject to appeal afterwards, unless “they involve matters of substance.”

- Workers in Federal agencies will be expected to work a 48-hour work week, unless the head of their department deems it impractical. Compensation for the extra time will be determined by standard pay schedules.

- Requirements that workers who have retired under age 60 due to disability report for annual medical evaluations and detail any wage or self-employment income they have earned during the year will be suspended.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Chapter 32 includes a series of “Emergency Regulations” regarding the operations of Federal Reserve banks. It is dated January 15, 1962 and issued over the signature of Merritt Sherman, Secretary of the Board of Governors.

Highlights include:

- All Federal Reserve banks and branches are to remain open for the transaction of business during their normal business hours, regardless of the status of the rest of the network. As with the emergency regulations for private banks (see “The Treasury Department,” above), exceptions are provided for those Federal Reserve banks located in areas rendered unsafe or whose essential personnel are killed or missing.

- Any Federal Reserve bank or branch that survives the initial attack is empowered to perform the functions of any other bank or branch that has been shut down, with the provisos that the Board of Governors is to be notified of the takeover “as soon as practicable,” and that the functions are to be handed back to the shuttered bank “when the cause of disability has been removed.”

- Each Federal Reserve bank is authorized to impose any restrictions on the distribution of bills and coins that it deems necessary “to assure the effective and equitable use in the public interest of all available supplies.”

- Federal Reserve banks are to make credit available to both member and non-member banks. They are authorized to waive the standard paperwork associated with such transactions, if doing so is necessary to keep money flowing; “considerations of formality of contract, security, and maturity of advances should be regarded as secondary to the problem of meeting the obvious essential needs of banks.”

- Parties who wish to borrow from Federal Reserve banks are to be allowed to do so on the basis of a promissory note (secured or otherwise). Parties borrowing against assets that have been rendered temporarily inaccessible are permitted to hold those assets in trust for the bank pending such time as they can be secured and delivered.

- Requirements that Federal Reserve banks maintain a particular amount of gold certificates in reserve are waived, with the proviso that the Board of Governors is to be notified when the amount held falls below 25% of the reserve requirement.

- Commercial banks which can no longer obtain loans or sell securities “on reasonable terms,” and whose management concludes that “it will be unable to meet foreseeable demands for withdrawals, transfers, or other payments,” are entitled to pay their obligations to other banks with promissory notes payable to a Federal Reserve bank. These notes are to be secured by the bank’s holdings of U.S. securities, and are to bear no interest. Parties who receive such notes in payment are required to honor them.

Housing and Home Finance Agency

Chapter 33 contains several orders describing the organization and operation of this agency (which was shortly to be folded into the new Department of Housing and Urban Development) “in the period immediately after an attack upon the United States.” They are dated variously between 1959 and 1965 and signed by several different officials.

Highlights include:

- An “HHFA Emergency Field Service” is to be established, to coordinate agency operations at the local and regional levels during a time when it is assumed central guidance from Washington will be unavailable. Nine regions are established, with a headquarters city designated for each, and existing offices from which Emergency Field Service offices are to draw staff and resources are listed.

- Regional and state directors of the Emergency Field Service are authorized to exercise “all powers now or hereafter vested in or assigned to the Housing and Home Finance Administrator” within their jurisdiction.

- A line of succession for the office of Housing and Home Finance Administrator is established, to go into effect “in the event the Administrator is unable to act by reason of his absence, illness, or other cause.”

- Several pre-written orders, needing only to be dated and signed by the Administrator (or Acting Administrator, in his absence) in order to go into effect:

- An order suspending all “nonessential programs and activities” within the agency;

- An order directing all Federally-owned or controlled housing (“and related facilities”) be used for the lodging of refugees, save for those facilities operated by the Department of Defense, the Atomic Energy Commission and other agencies directly related to the war effort;

- An order authorizing agency leaders (including those of the Emergency Field Service) to let contracts on their own authority, and to waive the normal procedural steps such contracts require;

- An order authorizing agency leaders (including those of the Emergency Field Service) to “requisition survival supplies, equipment and facilities or real property to provide housing and related facilities for dislocated persons and employees of essential industries”; and

- An order authorizing agency leaders (including those of the Emergency Field Service) to spend money on the agency’s behalf, and, when available funds are exhausted, to “pledge the credit of the United States.”

Interstate Commerce Commission

Chapter 34 contains several orders relating to transport and other economic activities regulated by the ICC (which was closed down in 1995). They are variously dated between 1962 and 1964, and issued over the signatures of ICC Chairmen Rupert L. Murphy and Abe McGregor Goff.

Highlights include:

- Operators of intercity rail and road transport services are ordered to accord privileged status over “all other traffic” to military personnel, government officials and U.S. mail. If necessary to provide such status, operators are authorized to limit or restrict the access to their service they provide to other passengers and types of cargo.

- For 48 hours following the declaration of a state of emergency, rail operators are prohibited from shipping any cargo into an area “which is being or has been subjected to enemy action.” Cargo shipped by the Department of Defense, the Atomic Energy Commission, or which is shipped “under civil defense symbol” is excepted from this ban. After the 48 hour period expires, cargos are only to be delivered into these areas if approved in advance by a Federally appointed agent.

- Similar to rail transport, motor carriers (i.e. trucking services) are to initially be prohibited from transporting goods into attacked areas, but for them the prohibition will last 72 hours instead of 48. After that period they are to be allowed to resume shipping into these areas, but under a different permitting system than that described for rail.

- Carriers by water on inland waterways are also prohibited from shipping anything into attacked areas for 72 hours. When that period ends, the approval process for their cargos is the same as that for motor carriers.

- Nine types of cargo are specifically listed as having priority over all other goods when being shipped into areas that have been attacked. These are military/AEC/civil defense shipments; food, for human consumption only; medical and hospital supplies; supplies needed for restoration of transportation and utility services; fuel; shipments assigned “emergency ratings” by the U.S. Department of Commerce; first class U.S. mail; newspapers; and “other shipments when transportation conditions permit.” Among these, the highest priority is to be accorded to military, AEC and civil defense cargos.

- Should a carrier’s cargo be rendered undeliverable due to enemy action, the carrier is ordered to store the cargo in any convenient facility “and to request further shipping instructions.” In the case of perishable goods, if such instructions are not received within 72 hours, the carrier is authorized to sell the cargo to whomever they can find to buy it; any profit from that sale, however, must be handed over to the shipper.

- Persons owning railroad tank cars, motor vehicles used for commercial transport, and liquid transport vessels are notified that they must comply with any directives received from the ICC as to the use of these vehicles for the duration of the emergency. ICC requests are to take precedence over any other tasking, including previously established contracts. Payment for usage of these cars will be at the ICC’s discretion.

- Bus services providing intercity service within a radius of 100 miles of any attacked community are ordered to transport any persons who ask out of the affected area to destinations up to 300 miles away from the attack zone. They are authorized to charge these passengers “at the carrier’s lawfully published rates, fares or charges.”

Federal Home Loan Bank Board

Chapter 35 sets out a set of emergency regulations for this agency. Dated November 16, 1964, they are issued over the signature of Secretary Harry W. Caulsen.

Some highlights:

- Savings and loan institutions are to refuse to permit any withdrawals or to issue any loans for the duration of the emergency, except in cases related to reconstruction expenses, essential living costs, tax payments, and payrolls. A signed certificate attesting that the purpose of the transaction is one of these approved purposes is to be considered sufficient proof to authorize the transaction.

- Savings and loan institutions “in an area directly affected by military action” are authorized to borrow money from any Federal Home Loan Bank without any restrictions based on amount or security.

- Should a debtor to a savings and loan institution suffer the destruction of the assets or property from which they derive income, or their earning power be reduced through injury or death, the institution is authorized to defer repayment of their debt “until the Federal Home Loan Bank Board shall otherwise provide.”

Railroad Retirement Board

Chapter 36 lays out emergencies regulations for this agency. Dated November 20, 1964, they are issued over the signature of Secretary Lawrence Garland.

Highlights include:

- A detailed line of succession is established for the office of Chairman of the Board, should the incumbent become absent or incapacitated.

- Regional directors who can no longer communicate reliably with the Chairman of the Board (or his successor) are delegated complete authority to act on personnel matters. Fiscal authority is to be more restricted, passing only to “emergency certifying officers” who could be appointed by either the national leadership or local/regional leaders.

- Applications for retirement, disability, and survivor benefits, as well as claims for sickness and unemployment benefits, are to continue to be processed “to the extent possible” throughout the duration of the emergency. Standards of evidence in evaluating these applications are permitted to be relaxed, however. In cases where the standard forms for these processes are not available, “any writing that contains substantially the necessary information shall be acceptable.”

- Employers are still required to pay their contributions into RRB retirement plans, and to report the hiring of new employees, unemployment and sickness claims, and so forth to the RRB. In cases where the emergency renders it impossible for them to do so, they are required to resume payments and reporting “as quickly as possible in the post-attack period.”

Ch-ch-ch-changes: 1968-1981

No volume of regulations can sit unchanged forever, and the CEFR was no exception. Periodic updates were issued to the document over the years it was in effect, with the first coming in 1968 and the last in 1981.

Many of the changes involve updates and edits to older documents, so a full accounting of how they changed the state of the CEFR over time will need to wait for the raw text to be extracted from the PDFs so we can apply textual analysis to them. Still, I wanted to call out some of the more obviously important modifications that the changes brought, so I will attempt to do so below. (Note that these are based on my first impressions upon reading the documents only, and are subject to change should my understanding of the scope of a given change alter later.)

Change No. 1, dated October 1, 1968, adds sets of regulations for two agencies not included in the original CEFR: the Office of Emergency Planning (OEP) and the General Services Administration (GSA).

A new Chapter 3 concerns the OEP. Highlights include:

- Procedures are established for releasing critical strategic materials (ranging from cobalt to castor oil) from various national stockpiles. In cases where communications between OEP regional offices and the national office are not operable, OEP Regional Directors are authorized to release materials stored within their area of jurisdiction.

- Pre-written forms authorizing the release of strategic materials from these stockpiles are provided.

A new Chapter 39 concerns the GSA. Highlights include:

- In cases where demand from other agencies for items from GSA inventories will exceed supply, a hierarchy of orders is established to allow requests to be triaged. Military and defense requests are prioritized highest, followed by requests for civil defense or recovery operations, requests “in support of essential programs for the maintenance or reestablishment of Government authority and control,” and requests in support of essential communications and transport services.

- GSA is authorized to provide “usable substitutes” in cases where a requested item is not available.

- Agencies will be billed for goods requested from GSA inventories at rates listed in the most recent GSA stock catalog prior to the attack.

Change No. 2, dated December 1, 1968, adds a new Chapter 38 for an agency not included in the original CEFR: the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB).

Highlights include:

- An Air Priorities Board is established to set priorities for use of limited air transport resources to move passengers and cargo. To head this board, an Administrator of Air Priorities is to be appointed from the staff of the CAB.

- A set of five priority levels are established: Class 1 (“utmost urgency”), Class 2 (“essential”), Class 3 (“important”), Class 4 (“eligible”), and “non-priority.”

- Cargo and passengers considered essential to the prosecution of the war effort are to be accorded priority status, so long as a deadline exists by which they must be at their destination and their transit has been authorized by a “competent authority.”

- Cargo and packages over five pounds per package in weight will not be permitted to be transported by air before priority and clearance for their transport have been established.

- Passengers wishing to travel by air will need to apply to have each leg of their travel prioritized before traveling. Applications are to be accepted by mail, by telephone or in person, and must include the name of the sponsoring agency or individual, the name of the person who will use the priority, locations to and from which they are traveling, the earliest time they can be available to depart, the latest time they can arrive and still achieve the objective of their travel, and justification both for the trip itself (relative to the overall war effort) and any baggage they intend to carry.

- Mail designated for air freight, along with mail parcel post weighing under five pounds, is to be automatically designated as Class 3 (“important”) priority.

- Various pre-written forms (application for priority, notice of approval/denial of application, etc.) are provided for use as needed.

Change No. 3, dated March 1, 1969, adds two new chapters: one (Chapter 12B) for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and another (Chapter 21) for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The new regulations for HUD replace the regulations in the original CEFR for the Housing and Home Finance Agency.

Highlights of Chapter 12B include:

- A Memorandum of Understanding between the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of the Treasury is included, outlining the places where their agencies would cooperate “in connection with the production and distribution of alcohol under conditions of national emergency.”

The new Chapter 21 mostly recapitulates the regulations established in the original CEFR for the Housing and Home Finance Agency, changing the names of offices and titles from “HHFA” to “HUD” as appropriate.

Change No. 4, dated June 1, 1969, includes major revisions to Chapter 12A (Treasury Department/Fiscal Service).

Highlights include:

- A new “Emergency Disbursing Plan,” covering how funds for government agencies are to be provided during the emergency. It specifies that

- Lines of succession have been defined for regional disbursing officers across the country, should they be killed or incapacitated. These officers (or their successors) are also authorized “to perform emergency functions independently and without direction” should communications with national leadership be severed.

- Primary and alternate emergency relocation sites are defined for all regional Treasury offices. If an attack is deemed imminent, some staff from each office will relocate to the primary relocation site in order to provide a backup presence should the main regional office be destroyed. Even after this dispersal, however, main regional offices are to continue operating “as long as conditions permit.”

- Emergency relocation sites have been stocked with “emergency disbursement kits,” containing “a supply of Treasury Department paper checks assigned emergency disbursing symbols, plus certain pieces of essential equipment such as typewriters, adding machines, check signers, etc.” Symbols on the checks are unique to the relocation site they were provided to. Staff are instructed that these resources are to be used “only in an emergency for on-the-spot payments to meet the requirements of administrative agencies.”

- Printing materials for official checks have also been stockpiled in various locations, to ensure that new checks can be printed even if all pre-war stockpiles have been destroyed.

- Each regional office that manages payroll records electronically has established an off-site storage location for backups of its magnetic tape and punched-card records. The data stored in these locations are updated monthly.

- Under current law, payments can only be made on vouchers that are “certified by the head of the department or agency or by an official or employee thereof duly authorized in writing to certify such vouchers.” It is noted that this could cause problems in an emergency, when department heads may not be available. Agencies are urged to make plans in advance of the emergency for how they intend to certify their vouchers so that payment is not interrupted.

- Instructions for how checks drawn on the Treasury are to be paid during the emergency are provided. Federal Reserve banks are to pay all such checks, without “examin[ing] such checks for genuineness of drawer’s signatures or for alterations.”

Change No. 6, dated June 1, 1970, includes significant changes to Chapter 39 (General Services Administration).

Highlights include a new “Emergency Contracting Regulation.” It:

- Authorizes agencies which have been delegated contracting powers during the emergency to “enter into contracts and into amendments or modifications of contracts… without regard to the provisions of law relating to the consummation, performance, amendment or modification of contracts whenever such action would facilitate the national defense.”

- Authorizes contracting parties to award contracts without the usual process of advertising the opportunity.

- Authorizes contracting parties to award contracts to bidders other than the lowest-cost one, “where a showing is made that the national interest is best served.”

- Authorizes the use of oral requests for proposals and price quotations, but instructs that requests for proposals should be in writing “to the extent practicable.”

Change No. 7, dated March 1, 1971, includes significant changes to Chapter 39 (General Services Administration).

Highlights include a new “Emergency Requisitioning Regulation.” It:

- Requires any representative of the government commandeering real property (e.g. houses, buildings, etc.) for public use to provide the owner(s) of that property with a kind of receipt, a new form called an “Order of Taking.” A draft copy of this form is provided. “All feasible efforts” are also to be made to file another copy of the form at the appropriate location where local real estate records are maintained.

- Instructs requisitioning authorities that an offer for a fair amount of compensation for the use of the requisitioned property is to be made to the owner(s) “[a]s promptly as practicable.” A process is outlined for the property owner(s) to appeal the amount of this offer. Final judgment is to be made by “a board or official formally designated by the requisitioning authority.”

- Exempts military commanders, civilian defense personnel and local emergency authorities from having to follow these rules in the performance of military, civil defense and reconstruction missions.

Change No. 8, dated August 1, 1971, includes significant changes to Chapter 38 (Civil Aeronautics Board).

Highlights include a new “Air Transport Mobilization Order ATM-2.” It:

- Notes that the existing priorities system defined by earlier CEFR regulations “may not be possible to implement immediately” during the emergency.

- Establishes a new set of priorities for air carriers to follow when shipping passengers and cargo “at the onset and during the initial period of a declared national emergency”:

- For passengers, priority is to be given to military personnel with authorized air travel transportation requests, military personnel bearing orders authorizing them to travel by air, and Federal, state and civil officers bearing travel requests or orders authorizing air travel.

- For cargo, priority is to be given to any armed forces cargo, government cargo, or industry cargo which is certified on its bill of lading as “shipment by air authorized.”

- Passengers and shippers of cargo who do not have the appropriate documents to qualify for priority travel can apply for such status on the grounds that their activities are “essential to the national emergency.” To aid carriers in evaluating such requests, a list of fourteen activities which would qualify as “essential” is provided; it includes military missions, law enforcement, firefighting, reconstruction and repair of communications systems, and radiological decontamination. Sample forms for such application are provided.

Change No. 11, dated June 1, 1973, includes a new Chapter 22 with regulations for the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

Highlights include:

- The establishment of an “Emergency Highway Traffic Regulation” (EHTR) program. Each state is instructed to assemble a plan for highway traffic management during the emergency. These plans are to be activated “when highway users must be protected from fallout resulting from a nuclear attack”; “when traffic demand exceeds highway capacity”; and “when unauthorized traffic should be excluded from a specific area.”

- A standby order establishing procedures for highway repair and reconstruction “immediately following an attack upon the United States.” In situations where communication with national authorities have been cut off, Regional Federal Highway Administrators are granted wide authority to spend money, let contracts, requisition property and employ people for the purpose of “the emergency clearing, repair, or restoration of highways, bridges, streets and roads deemed essential in view of the emergency.” A form is provided to enable the Federal Highway Administrator to put this order into effect.

- A standby order requiring state highway departments to collect estimated resource requirements for repairing highways within their jurisdiction in the event of a national emergency, and to periodically provide these estimates to the FHWA. A form is provided to enable the Federal Highway Administrator to put this order into effect.

- A standby order defining the scope of FHWA powers to requisition private property for highway reconstruction during the emergency. A form is provided to enable the Federal Highway Administrator to put this order into effect.

- This power, “one of the most drastic powers exercised by the Federal Government,” is to be used “only when necessary in support of military operations or survival of the population of the country.”

- The power to authorize requisitions is restricted to the Federal Highway Administrator, except in cases where regional offices are cut off from communicating with national leadership. In such cases, authority to requisition is delegated to Regional Federal Highway Administrators and Division Engineers.

- In cases where property is requisitioned, owner(s) of the property are to be issued an Order of Taking. Copies are also, “where feasible,” to be filed wherever local property records are maintained.

- Owner(s) of requisitioned property are to be provided with an offer of compensation, and given the opportunity to appeal this offer, as outlined in the CEFR orders for the General Services Administration (see “Change No. 7,” above).

- A standby order stopping all highway construction throughout the United States, so that materials can be used for reconstruction and recovery. A form is provided to enable the Federal Highway Administrator to put this order into effect.

Change No. 12, dated March 1, 1977, includes a new Chapter 17 with regulations for the Department of Agriculture (USDA). They are issued over the signature of Ford Administration Agriculture Secretary John A. Knebel.

Highlights include:

- “Defense Food Order No. 1,” outlining the procedures for affected parties to appeal USDA decisions made during the emergency.

- “Defense Food Order No. 2,” empowering the “Order Administrator” — defined as “the Secretary of Agriculture or any employee to whom authority has been delegated” — to “control the processing, storage, and wholesale distribution of food,” with authorization granted to take any actions necessary to impose and maintain such control.

- “Defense Food Suborder No. 2A,” imposing several requirements on processors of food:

- They are to “continue their normal processing operations to the extent practicable,”with two exceptions:

- Use of sugar and other natural sweeteners is to be restricted to no more than 50% of “normal recent or seasonal use”;

- “All reasonable precautions” are to be taken to ensure that products produced are fit for human consumption; products that do not meet this standard are to be either held back from distribution, or processed again into something that does.

- They are to distribute their products to existing customers “as equitably and consistently as possible.”

- They are to distribute their products to “other potential customers in need of food” as well, though such distributions can be made contingent on agreement upon “financial arrangements.”

- They are to limit their distribution of products to either the rationing levels defined in Appendix 1 (see below), or to state or local rationing levels, whichever is less.

- They are not to distribute their products “outside of established trade channels,” except in cases of special distribution locations set up by state and local authorities or where authorized by the Order Administrator.

- They are not to distribute their products “directly to ultimate consumers,” except where authorized by the Order Administrator.

- “Appendix 1 of Defense Food Suborder No. 2A,” defining a rationing regime for distribution of foodstuffs:

- Table 1 defines the maximum amounts of various types of food allowed to be distributed per person per week for the duration of the emergency.

- Meat: 3 pounds boneless, 4 pounds bone-in.

- Eggs: 6.

- Milk: unlimited.

- Cereals: 4 pounds.

- Fruits and vegetables: 2 pounds (frozen).

- Food fats and oils: ½ pound.

- Potatoes: 2 pounds.

- Sugars, syrups and honey: ½ pound.

- Table 2 defines acceptable substitutes for foodstuffs should some part of an individual’s allowed ration not be available.

- Table 3 defines rates at which canned, dry and concentrated foods can be substituted for fresh within an individual’s ration.

- “Defense Food Suborder No. 2B,” regulating the terms under which food processors are to provide food to the military:

- Processors with existing military contracts are to “make every practicable effort” to fulfill those contracts.

- Food processed under such contracts but undelivered to the military is to be held by the processor for 30 or 60 days (depending on type) before being released for civilian consumption.

- Processors not currently under military contract, but which had military contracts in place up to a year before the emergency, are to set aside for military use an amount from both existing inventories and future production equal to the percentage of their overall production their military production represented over the last year. This food is to be held for military pickup for up to 30 days.

I finally got around to seeing the most recent film from director Nicholas Winding Refn, last year’s

I finally got around to seeing the most recent film from director Nicholas Winding Refn, last year’s  Disclosure: I was provided a free pre-publication review copy of this book by the publisher via

Disclosure: I was provided a free pre-publication review copy of this book by the publisher via

Disclosure: I was provided a free pre-publication review copy of this book by the publisher via

Disclosure: I was provided a free pre-publication review copy of this book by the publisher via

Disclosure: I was provided a free pre-publication review copy of this book by the publisher via

Disclosure: I was provided a free pre-publication review copy of this book by the publisher via

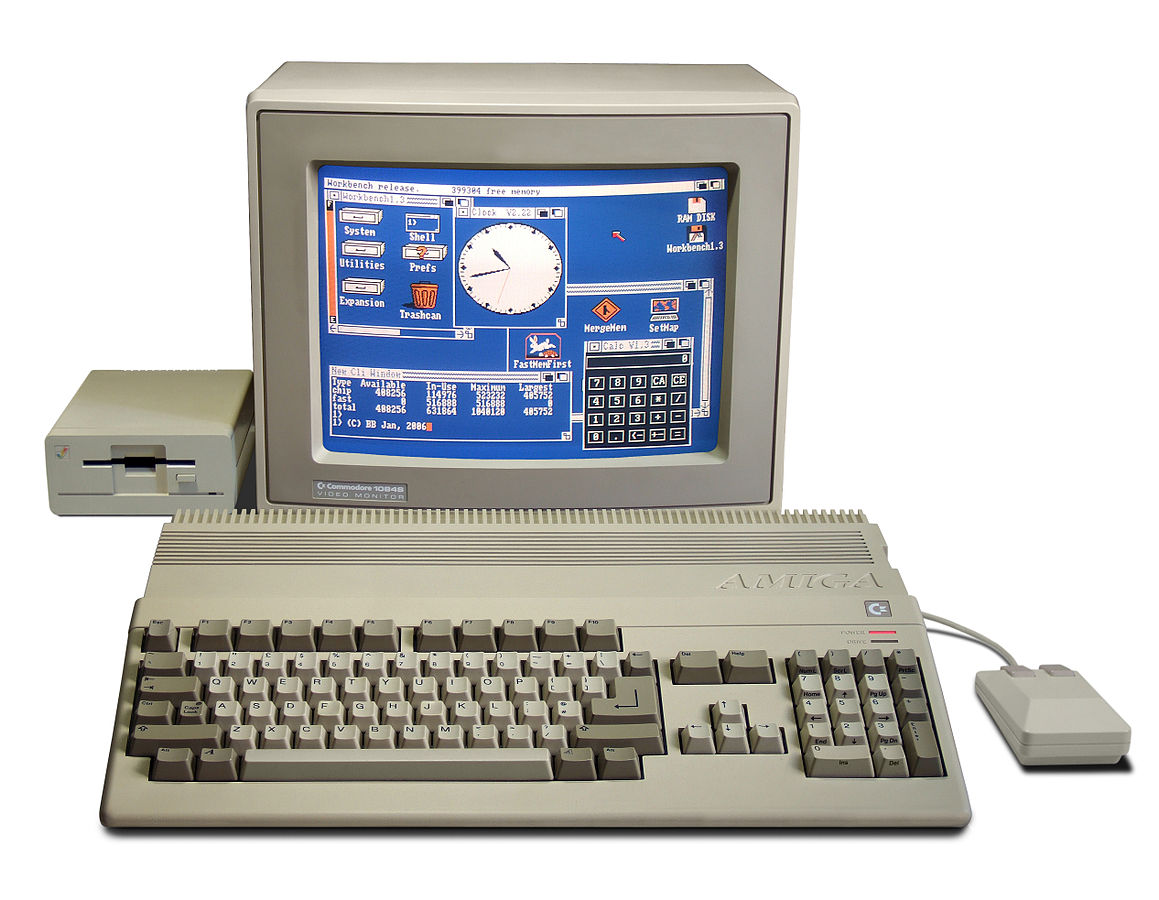

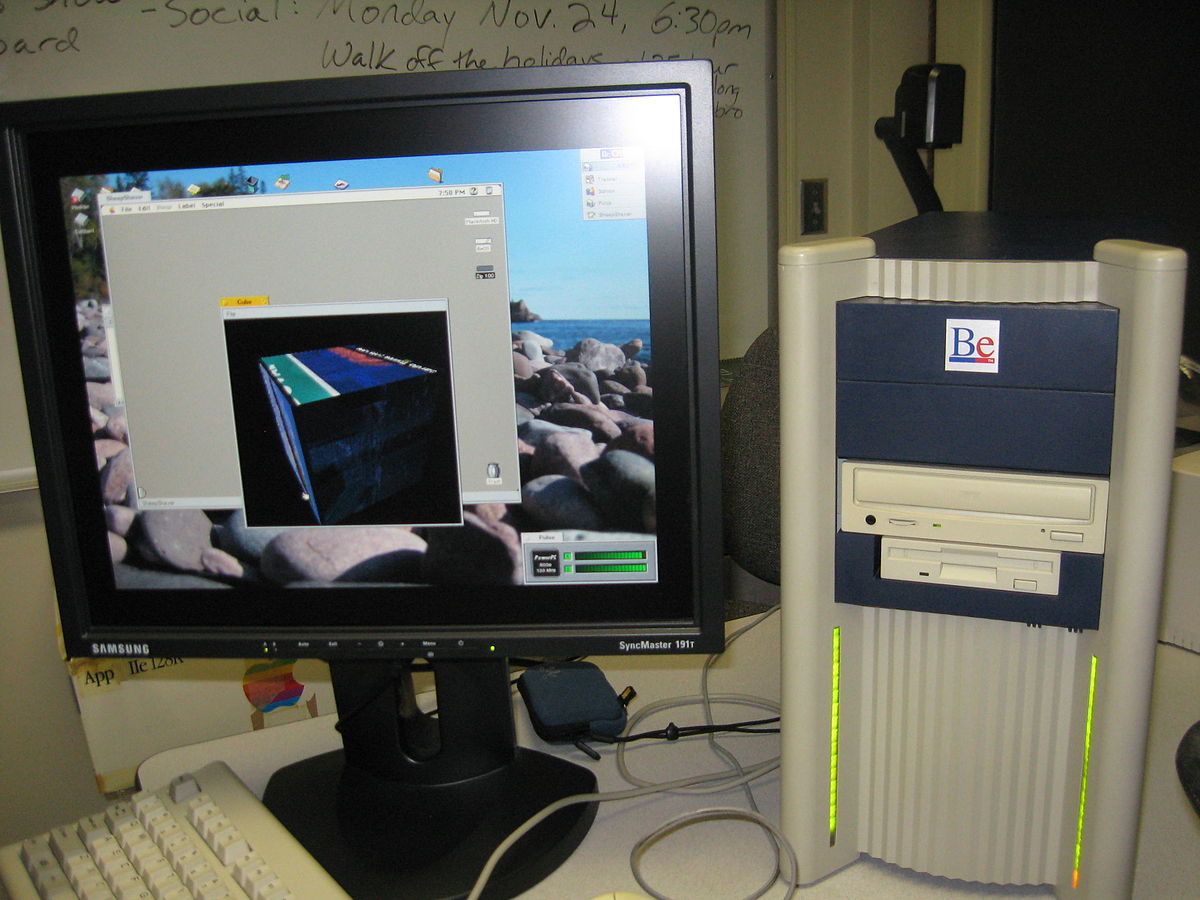

Hang around with nerds enough and you will eventually hear some version of the following sentiment:

Hang around with nerds enough and you will eventually hear some version of the following sentiment:

So last week

So last week

If you live on or near the East Coast of the United States, the odds are pretty good that you had trouble accessing one or more of your favorite Web sites this morning. That’s because of

If you live on or near the East Coast of the United States, the odds are pretty good that you had trouble accessing one or more of your favorite Web sites this morning. That’s because of